A comment of mine came up again in the memories section of my Facebook timeline earlier in the week, and got me spiraling down the same rabbit hole once again. I’d first posted it seven years ago, but it retains its relevance still in terms of people who are creating works of serialized heroic fiction. I’m pretty sure that it was written in response to some spirited defense of MAN OF STEEL, the Zach Snyder film, by some of its proponents. These fans fought tooth and nail to express their admiration for the version of Superman presented in that film—which is their right. But in a larger sense, it was their willingness to forgive any wrongdoing that the character might have made—in particular, of course, his killing of General Zod during their final battle—as being permissible because he was the hero.

And so, my question was: If your hero is allowed to do everything that the villain can do, then apart from having his name on the cover, what makes him the hero? If it’s okay for your hero to lie and cheat and steal and kill and maim and destroy, what makes him the good guy apart from marketing? This is a question that comes up a lot in my business, as you’d expect, and it’s something that can easily get overlooked in the rush to get stories created and out the door. But I think the thing that makes your hero a hero is having a consistent moral code that guides his or her actions, one that they will not veer from. It doesn’t need to revolve around killing or not killing—plenty of film heroes kill people. Rather, it’s the understandable lines that they will not cross, while their enemies will cross any line, perform any deed, in order to get what they want. Heroism is, in a certain respect, about restraint, about having honor, about behaving decently. And I think as we lose sight of that idea, as our heroes are allowed to do the easy thing more often than the hard thing because it’s more visually spectacular, as we let our heroes throw the first punch or land the first killing blow, we steadily erode the bedrock that lends them widespread appeal. There are certainly plenty of people who like Batman because he’s an unrelenting badass, and the fact that he doesn’t kill people doesn’t enter into it—they’d like him better if he did (and, let’s face it, in the movies, he often does.) But I don’t think that interpretation is appealing to a wide audience. Your hero can’t simply be the hero because he’s on the marquee. He or she needs to walk the walk—whatever the established parameters of that walk are.

We’ve got fewer questions this week than normal, which I suspect is just the regular ebb-and-flow of things. Hopefully, we can drum up a couple more in this coming week, so I don’t have to vamp so much. Anyway, let’s start out with this involved one from Manqueman:

Among my nearly lifelong obsession with how sausages are made, in this case, comics, I frequently ponder the economics. This has focused on the perennial problem of making a reasonable living in comics (as in earning enough for housing, medical insurance (at least for American creators IYKWIM), and actually saving money for slow periods in the freelancer's life. More recently, it's also been the manifestation of what should be expected: the failure huge number of companies filing for bankruptcy or even going out of business. Oni, Valiant, Aftershock, Heavy Metal... and I presume new management will eventually catch up to DC once the former's dealt with CNN, HBO and Warner/DCU.

In regard to the latter, as I understand it having no inside info: sales of 5,000, 10,000 or even 20k at $4/per. So let's say a book gets a $80,000 gross. Publisher gets around half. Of that $40k or less, there's overhead and a couple of creators and... well, I don't see anyone getting wealthy -- or businesses lasting for the long haul.

So my question, Tom, is what do you think of this:

https://www.comicsbeat.com/tiilting-at-windmills-293-whats-wrong-with-the-periodical-comics/

https://www.comixexperience.com/news/2023/1/2/comix-experience-best-sellers-2022

I should add that since Hibbs' piece covers more than just economics but the issue of high numbers of variants and the effect of cover prices, I'm also curious of your thoughts if, you know, can.

Honestly, that sounds like a homework assignment to me, Manqueman, but I took a look at it. And I agree in general that the periodical business is a tough business to be in at the moment, there’s no getting around that. What folks fail to take into account, though, is that the periodical model is still necessary in order to cover the cost of the material in question. Put simply, while not every Marvel title is profitable to the degree that we need it to be in order to cover our operating costs—the “margin”—there really isn’t a Marvel comic that loses money once you factor in collected editions. That’s because the revenue generated for the collection doesn’t need to cover the cost of the material being printed—it only needs to accommodate the agreed-upon incentive payments due to the creators. And with that, the number of titles that we publish is predicated on the number we need to remain operational. So I get what Hibbs is saying, it’s always been rough to be a front lines Retailer like he is. By that same token, I find that if you ask ten different retailers for their opinions concerning variants, you’ll get ten very different and very subjective ideas, based on what works for that particular Retailer in their particular area with their particular clientele (and what they themselves prefer as an individual.) Our team talks with these guys on a regular basis, and we do our level best to take all of that feedback on board and to behave responsibly, so that everyone in the chain of production can survive and thrive, and the marketplace can remain healthy. We certainly foul up from time to time, but that’s what our focus is on. So while it’s easy to think that the market would be better if there were fewer titles, the fact of the matter is that the market would be non-existent if that came to pass—companies couldn’t cover their overhead, and shops couldn’t generate enough income to cover their operating costs.

Next, Steve McSheffrey says:

And as to Ultimate Universe, has anyone ever pitched doing an Ultimate line again with another continuity do over?

All the time, Steve, pretty much since the day that the original Ultimate line shut down. Hasn’t happened yet, but who knows what the future might bring? That said, I think it’s extremely difficult to capture that lightning in a bottle again, a lot more difficult than most folks seem to think. I look at the attempts to do similar things, such as DC’s EARTH ONE line, or even its NEW 52 relaunch. Both of them got some short-term attention before losing that spark—and in the latter case, then they were left with a publishing situation that they’re still trying to untangle years and years later. That sort of big reboot can be exciting, but by definition it requires the baby and the bathwater to be put on the line equally.

And finally, the amusingly-named Mortimer Q. Forbush asked:

I am always so gobsmacked to hear stories of John Romita's assessment of his own skill; partially because I grew up with his incarnations of all my favorite Marvels as the Standard (with all due respect to Kirby and Buscema). Do you think he had a touch of imposter syndrome? Is that something you encounter much in your collaboration with a bevy of creative professionals? Moreover, as a hirer and firer of creatives, do you have any thoughts on the negative or positive ways it affects their output? As someone who either (a) feels imposter syndrome from time to time, or (b) is actually a legitimate hack; I find it heartening when I hear people I hold in high esteem talk about feelings of doubt in their own ability. Not out of schadenfreude, but because it makes me realize, "Oh…okay."

I think it’s a typical thing to find in the practitioners of any creative field, Mort. I mean, hell, I’ve been doing this job for going on 34 years now, and from time to time I stop and wonder about just what the hell I’m doing. I don’t know if it was impostor syndrome specifically with John, but it was certainly anxiety. By that same token, that anxiety drove him to chase excellence and to perfect his craft, and it kept him humble even as his skills magnified, as he was still in awe of the abilities of other cartoonists he saw all around him. I think it’s only natural to experience some degree of doubt in your own abilities—the important thing is to not let that hold you back.

Finally, a tip—or Chip—of the Hat to Chip Zdarsky, whose latest plug over at his own delightful Substack Newsletter resulted in another influx of new readers, to say nothing of an entertaining story about his pre-comics days.

Behind the Curtain

Here’s a letter that hasn’t been shown publicly as far as I can tell, but which circulated wildly in 1987.

.This letter was written by longtime Marvel inker Vince Colletta and sent to every member of the Marvel Comics editorial staff in the aftermath of Editor in Chief Jim Shooter being let go by the company. Vinnie was a close friend of Shooter’s, not entirely because as EIC, he always made sure that Colletta had work on his drawing table. I think it can fairly be said that Shooter’s last few years at Marvel were tumultuous, and there were points where he pissed off a lot of people—staff, freelancers and management alike. I know of at least one Marvel Intervention/Mutiny that happened, when a group of creators and editors all piled into Shooter’s office to air some grievances. In any event, Vince clearly laid the blame for Shooter’s ousting at the feet of the rest of the editorial staff—as well as his own assignments being cut off—and so he registered his displeasure in this fashion.

Pimp My Wednesday

More all-new comic book wonderment arriving in your town this Wednesday!

AVENGERS #65 passes the halfway point on the madness that is the Avengers Assemble storyline that wraps up Jason Aaron’s tenure at the helm, and this particular issue reveals the life and origin of Avenger Prime, the character responsible for creating the Avengers Tower within the God Quarry and gathering the multidimensional Avengers Forever to defend it. Artist Javier Garron leaves everything on the page, as he’s been doing all along.

MOON KNIGHT #20 is an oversized issue, featuring not only the Harlequin Hit Men and the return of several supporting players from the Crescent Crusader’s past, courtesy of Jed MacKay and Alessandro Cappuccio, but also a second back-up story in observance of Black History Month that guest-stars Blade and introduces an earlier Fist of Khonshu. It’s written by Danny Lore and illustrated by Ray-Anthony Height, and it’s not a throw-away, it ties directly into the series’ ongoing narrative, as you’ll see the following month.

And speaking of Blade, his daughter Brielle has her hands full as the nature of her heritage makes itself known to her, in the new BLOODLINE: DAUGHTER OF BLADE #1. This one's under the oversight of Associate Editor Annalise Bissa, and it was also written by Danny Lore, with artwork from Karen Darboe. It’s been a long road getting here, but finally we’re ready to introduce Brielle properly to all of you. It’s got a cool logo, too.

And in the world of digital media, AVENGERS UNLIMITED continues on with Jim Zub and Davide Tinto’s “Key To A Mystery” which sets Earth’s Mightiest Heroes against some of their greatest foes, for reasons that will become apparent.

Two Comic Books On Sale 80 Years Ago Today, January 29, 1943

Slim pickings this time, I’m afraid, in terms of comics that first saw print on this date. But here’s a pair of releases that I can at least say something about.

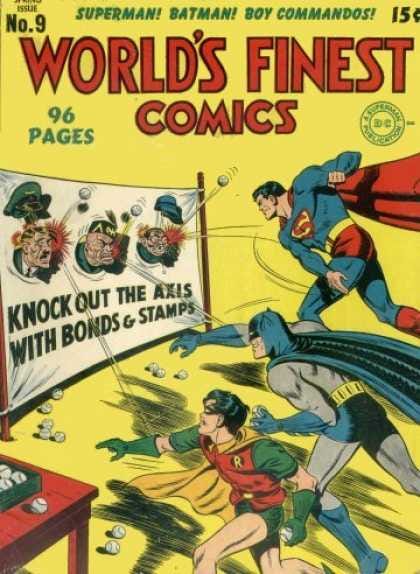

After having produced a pair of special commemorative comic books for the World’s Fair and finding good success with them, DC/National Comics decided to make the format a regular quarterly thing. And so was launched WORLD’S FINEST COMICS. (Actually, it was called WORLD’S BEST COMICS for the first issue, but another publisher with a similar title threatened a lawsuit, and the name was changed.) At a time when most regular comic books cost a dime for a 64 page package, WORLD’S FINEST increased the size of the package to a beefy 96 pages and put it behind cardstock covers. The big sales draw, and the cover feature, was Superman and Batman and Robin. They weren’t yet featured in the same story—that wouldn’t happen until page count decreases reduced the size of the package to the point where combining them into a single strip seemed like the best choice in 1954. Additionally, a number of other second banana strips were also included, all of them from the DC/National house (rather than All-America Comics, which shared co-ownership and also carried the DC bullet on its covers.) This included at various points Zatara, Green Arrow, Red, White & Blue, the Boy Commandos and many others. Of particular note concerning this issue is that it featured a rare and entirely-unheralded crossover between two different series. As I detailed previously at this link, in the Star-Spangled Kid story in this issue, the Kid and his pal Stripesy momentarily cross paths with the Joker, Batman and Robin for really no purpose whatsoever (apart from maybe trying to send the message that the Star-Spangled Kid and Stripesy were on the same level as the Dynamic Duo.) The other fun thing about these Golden Age issues of WORLD’S FINEST COMICS is their cover images. Rather than depicting the three heroes in wild, all-out action against some foe or criminal, they instead often went for quieter, more homey images: the trio racing soapbox race cars, or going to the fair, or swimming—literally just palling around, in a way that they never got to do on the interiors. Even on this issue, while the wartime propaganda is unfortunate in the manner in which the Nation’s enemies are grotesquely caricatured, the image is more one of fun than it is of serious conflict. What kid in 1943 wouldn’t want to bounce a baseball off of Adolf Hitler’s noggin?

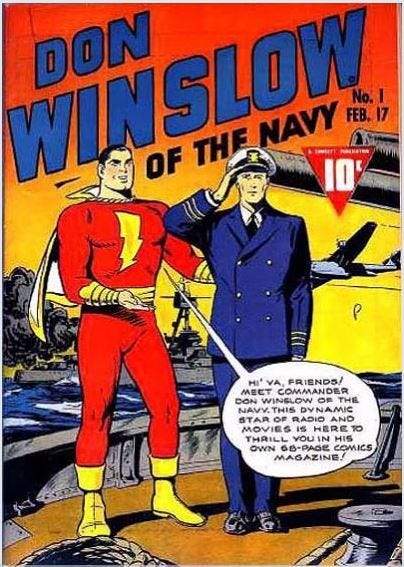

Also on sale 80 years ago was the first issue of DON WINSLOW OF THE NAVY. This is a strip that Mark Waid and I have chuckled at a little bit, in that it ran for years and years under the Fawcett Comics banner, but every issue reads very much like every other issue. There isn’t a whole lot to distinguish it. But that’s a 21st Century perspective. At the time of this book’s release, DON WINSLOW OF THE NAVY was a popular newspaper strip by Commander Frank V. Martinek (a Navy man himself, and also a veteran of World War I) that also spawned a successful daily radio show, and was also a movie serial from Universal, the first of two. In other words, any kid worth his or her salt in 1943 had heard of Don Winslow. The strip and its many permutations followed the adventures of Naval Lieutenant Don Winslow as he battled spies and saboteurs in patriotic adventures. In 1943, that was a winning formula. Another winning formula that Fawcett used again and again was to have their powerhouse star Captain Marvel introduce and endorse their new characters on the first issues of their comic books. The Captain Doesn’t appear in the issue beyond that, leaving it to the Lieutenant to take care of business. DON WINSLOW OF THE NAVY was originally conceived as a naked recruitment tool for the Navy, and its comic strip storylines were even approved by that branch of the armed forces. Accordingly, Winslow’s behavior was above reproach in every story—making him a bit colorless, if the truth is known. But that didn’t stop this series from running for 69 issues before finally coming ashore in 1951.

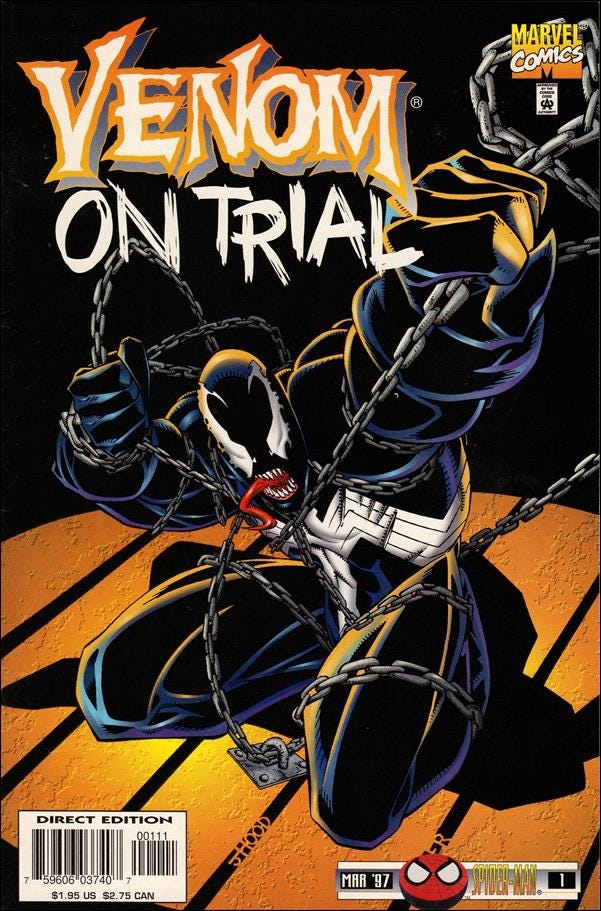

A Comic I Worked On That Came Out On This Date

I wound up as the editor of VENOM for several years in the 1990s, this despite my not having any great attachment for the character. Which is an occupational hazard: if you’re going to be an editor at a big comic book company, you have to expect to sometimes be tasked with handling titles that you really don’t care for. How you manage that is a good barometer of how well you’re functioning as an editor. I tend to think that I did so-so in this regard. My VENOM comics weren’t terrible, there was genuine effort expended on them. But I didn’t have the access to a lot of resources or a really instinctive sense as to what about the character was resonating with the audience. Possibly the most popular thing I did in the series was to drop the letters page and change it instead into a Venom Fan Art Page. We got mountains of drawings every month thereafter, far more mail than any other title in my area, all depicting Venom and all running the gamut from amateurish to almost-professional. As a rule, I tended to make sure there was one Fan art image from a very young fan every issue. Anyway, for some reason—a cynical cash-grab to enable there to be a string of VENOM #1s—VENOM wasn’t an ongoing title. Rather, it had been set up as a “series of limited series”, which meant that every four or five issues, a new storyline would have to start and a new marketing hook was going to be needed. This one, which saw the light of day on January 29, 1997, was VENOM ON TRIAL We’d had the Lethal Protector just wandering around doing whatever he wanted for a while now, and it never really sat right with me. This was no different than when Spider-Man would team up with the Punisher in order to take down some criminal who often was less bloodthirsty and caused less carnage than the Punisher himself—it always strained by suspension of disbelief that Spidey would just let the Punisher walk away to go kill some other people, criminals or not. And the reason he did so—and the reason why Venom got away with his misdeeds—was that his name was on the cover. So after a couple of stories, we decided that we needed to adjust that status quo, to make it more plausible, if only slightly. This is something that our editorial team—myself and assistant editor Glenn Greenberg, as well as possibly our intern of the moment—would work out with writer Larry Hama at a long lunch at Larry’s favorite eatery, Mister Leo’s. Larry wasn’t my hire, he had been brought onto VENOM with the limited series that preceded my first one, but he was a rock-solid and respected professional, and so he wrote the book all the way to its end. This storyline, as the title implies, sees Venom captured by the law and put on trial—his attorney is Matt Murdock, of course. A number of characters from the X-MEN universe play a role here, including Bastion—Larry was writing WOLVERINE at the time as well, and so he was able to cross-pollinate between the two series. The storyline also included extended appearances by Spider-Man and Carnage, of course. By the end, rather than facing justice, Venom was instead recruited into a shadowy government agency that would grant him clemency in exchange for running missions for them. It’s a bit cliché, especially in hindsight, but this at least left Venom in a position where he wasn’t simply at liberty because the series needed him to be.

Monofocus

Spent much of my week as described last time, watching the weaponized nostalgia of shows that are modern day sequels to older antecedents—a form that needs a name, and which I have coined Nos-Coms. I found the first, THAT ‘90S SHOW, to be not good, but rather a pretty perfect replication of the earlier series that it was a sequel to, warts and all. It wasn’t especially sharp, it wasn’t consistently funny, but the characters were likable enough, and the situations simple enough that they sustained the relatively short run time of every episode. they were like potato chips, easy to snack on and digest, not requiring a whole lot of thought or focus. it helps big time that Kurtwood Smith and Debra Jo Rupp reprise their characters from THAT ‘70s SHOW effortlessly, and looking as though virtually no time has passed. And those characters, Red and Kitty, work better in the role of grandparents than they did as parental figures. I was never especially fond of THAT ‘70s SHOW. I saw a bunch of it, though, as it aired on Fox in-between a number of its animated series that I was following in a time when view-on-demand wasn’t yet a thing. So there is some nostalgia there, if only in terms of the thing being familiar. But that wouldn’t have carried me through ten episodes if the series wasn’t hitting its marks, shallow though those marks may be.

Elsewhere, HOW I MET YOUR FATHER came back for its second much-extended series, and feels as though its found its rhythms a bit. The first year was a bit shaky, the characters in the process of forming on the fly and not becoming fully realized until late in the year. But the return episode was confident, even if the show still isn’t quite as clever and as risk-taking as its antecedent, HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER. Speaking of MOTHER, FATHER stacked the deck for itself a little bit in the opener by featuring a flash-forward to some later episode, in which the lead character Sophie has a fender-bender with Neil Patrick Harris, who returns to play Barney Stinson. This moment was pretty much the only thing that anybody who was covering television shows talked about in relation to the premiere, so it was probably a canny move to include it. It does point out a weakness in the series, however, if all that it has going for it to attract a viewship is the hope that one of the old actors from its predecessor will show up. that’s a card trick that’s going to run its course rapidly.

Also, even before Gerry Duggan (he of this Substack Newsletter right here) could recommend it, I had watched THE PEZ OUTLAW on Netflix, a cool documentary that outlines the career of self-styled Pez Outlaw Steve Clew, who both made and lost a fortune importing Pez dispensers and merchandise manufactured outside in Europe into the United States and selling them on the collectors’ market. It was the sort of low-stakes rags-to-riches-to-rags story that fascinates me, and while I don’t have any particular attraction for Pez products, the world is similar enough to that of comic book collectors that I could understand it instinctively. (There was a moment when one woman reveals that the most she’s ever spent on a single Pez item was $11,000 and I did a double take—and then remembered the prices that back issue comics routinely go for.)

And finally, I took in LUPIN III VS CAT’S EYE on Amazon Prime, which was a relatively unprecedented thing. I remember CAT’S EYE from its two animated series back in the 1980s, and I’ve read volumes of the manga—but I didn’t think it had been a going concern for some decades now. On the other hand, the characters clearly must have some footprint still in Japan, and their series set-up—they’re a trio of sisters who are secretly cat burglars, pursued relentlessly by a hapless Police Detective who is one of the girls’ fiancée—jigsaws together with the world of Lupin effortlessly. The actual film was all right, though the animation quality, with a heavy reliance on computer-generated graphics, wasn’t that great. There was also a limited amount of versus in this, as while both Lupin and the Cats are in pursuit of the same three paintings, they quickly wind up as uneasy allies before teh halfway mark of the production. And hey, since most readers here won’t be familiar with CAT’S EYE and I haven’t embedded any video links here yet, here’s a look at the original 1980s title sequence. Anyway, my final review is that this probably isn’t the place you’d want to start with LUPIN III, but if you’re already familiar with the franchise, it’s another solid entry in the series.

Posted at TomBrevoort.com

Yesterday, I took a look at the last Sub-Mariner story published before the Marvel Age began.

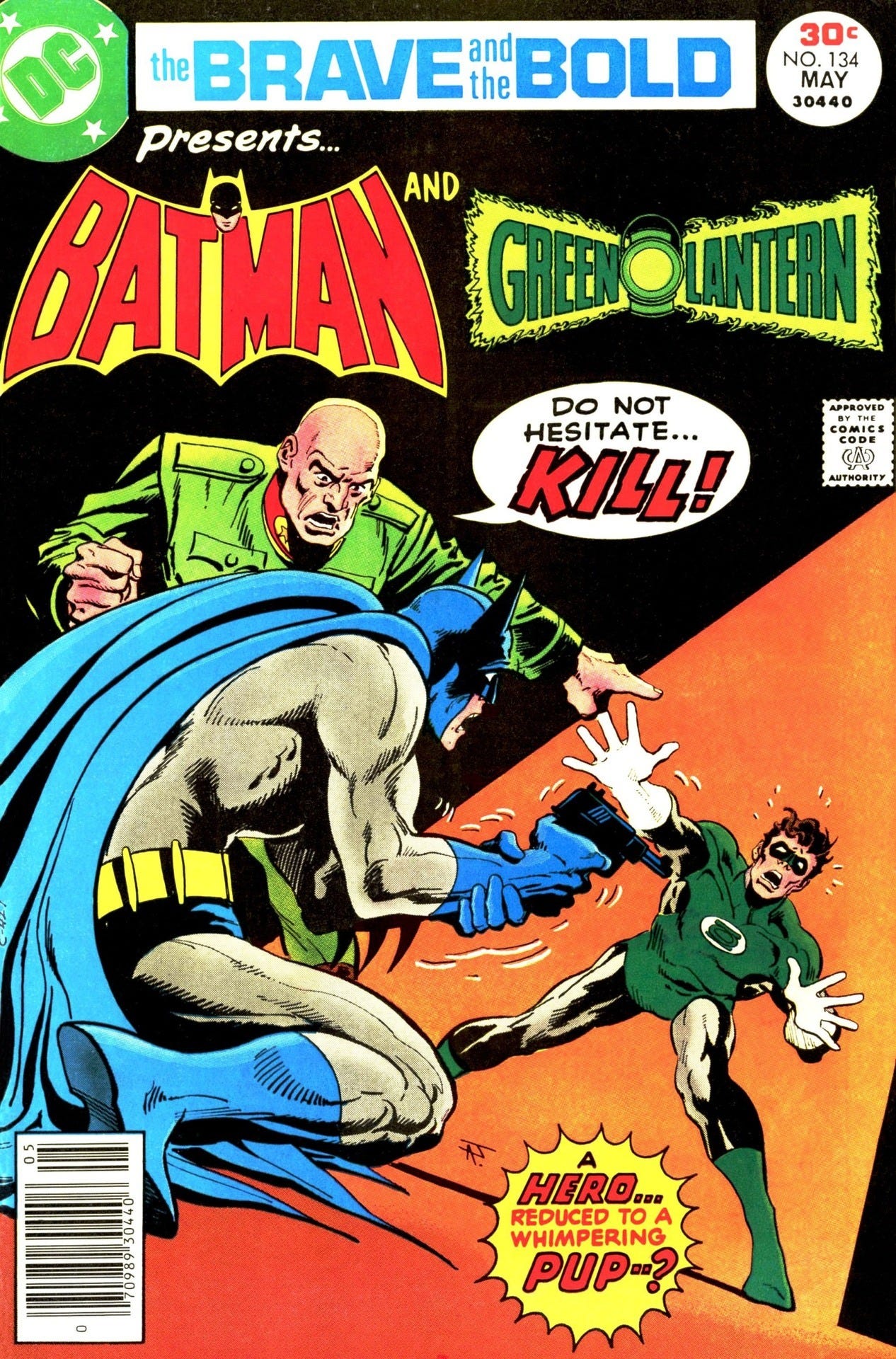

And five years ago, I wrote about this extremely strange issue of BRAVE AND THE BOLD starring Batman and Green Lantern.

Ladies and gentlemen: The End.

Tom B

The Coletta letter is insane! Wow!

Brings to mind a question in regards to the Shooter era - he definitely had an eye for talent - I mean look at his editorial line up - growing up in the 80s as a comic reader and looking back now I see how most of the editorial staff were also working on the Marvel titles as writers on long runs - what are your thoughts on this?

I heard it was to supplement income, as well as an incentive to work at Marvel, good training for editors to see how they put a comic together..etc.. which would sometimes work and sometimes backfire (Shooter mentions how Denny O'Neil would spend more time writing than editing). It was cool to see some editors be able to do it all: guys like Hama and Milgrom could write, pencil, layout, ink, color, etc..very cool skill set to have in a crunch I'm sure.

This seems to have stopped at Marvel (and DC) - why is that? Do you think this was a flawed process? Would you ever do something like this again?

Not a complaint as some of my fave runs were by writer/editors ; Nocenti on DD, O'neil on DD, Gruenwald on Cap and Quasar, Mackie on Ghost Rider, Stern, MCduffie, Larry Hama, etc..

Would love to hear your thoughts on this.

“No cry of help was too small for him to turn his back on.”

A way with words, that Vinnie Colletta.