Here’s another piece carried over from the TomBrevoort.com site to keep you company in the midst of a long month. One of the things that I’ve done a bunch of there has been relatively deep dives into aspects of comic book history, in particular Marvel history. So this is a piece that’s all about the different ways that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby worked on the material that they both worked on together over the years of their partnership. This is important to understand in that the dynamic between the two men evolved and changed over time, and there was no one way that they made their comic always. As the arguments over who contributed what are never likely to abate completely, this is an important factor to bear in mind.

Lee & Kirby: The Four Work Stages of Lee & Kirby

Tom Brevoort Lee & Kirby July 27, 2019

Whenever the conversation turns to the question of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby and their collaborations during the 1960s and who was responsible for doing what–a question that I don’t think can ever be definitively or conclusively answered–one of the misconceptions that I see come up time and time again is the notion that Lee and Kirby’s working relationship was a solid state affair–that the way the earliest issues of FANTASTIC FOUR were produced, and the division of labor on them, was the same as that of the very last issues of the series they worked on together. And this really isn’t the case at all. As Marvel grew and became more successful, and as Lee and Kirby worked together over a longer period of time, their methodology evolved. I can point to and define at least four specific phases that their partnership went through. Since this would seem to me to be information beneficial to the ongoing conversation about the two men and their work together, I thought I would lay all of this out for people.

Before we dive into this, a few words about terminology. One of the big problems in talking about this stuff is that all of the folks involved tend to use the same terms to mean different things. In the 1960s, the act of crediting comic book stories was a new thing, and largely pioneered by Marvel. Those credits were fine for the time, and give us a starting point for discussion, but in modern terms, they are inadequate to capture the nuance of the work that was being done by the contributors. So at least for the purposes of this piece (and in conversation in general) I am going to use the terminology that is today industry standard, as we would apply it to a comic book story created now. In such an instance, the writing of a comic book story is divided up between the PLOT, which is the essence of the story, the events that transpire on the page between the characters; and the SCRIPT, which is the specific copy that is lettered on the page: all dialogue balloons, thought balloons, captions and sound effects. Most comics of the modern era are back to being drawn from a FULL SCRIPT, which is to say a document that includes both stage directions and all dialogue and copy, in the manner of a screenplay. But for much of Marvel’s history, most of its stories were produced in what has become known colloquially as the “Marvel Method”. A writer would write a Plot, a breakdown of the events that take place within the story–either in great detail or just broadly–and from this the artist would draw the scenario out into the pre-requisite number of pages. From these illustrations, the writer would then produce the Script, which would thereafter be lettered onto the penciled boards. None of this is quite reflective of how Lee and Kirby worked together, but this method evolved from what they did, and this will be the terminology I will be using to describe matters.

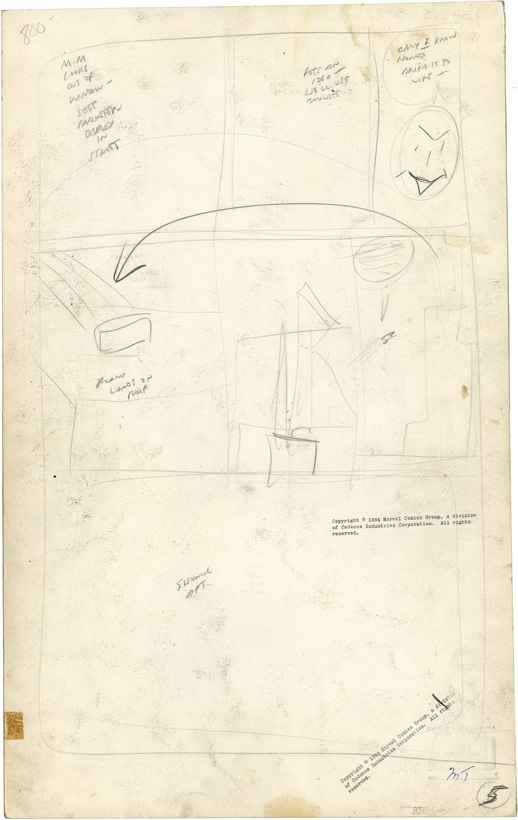

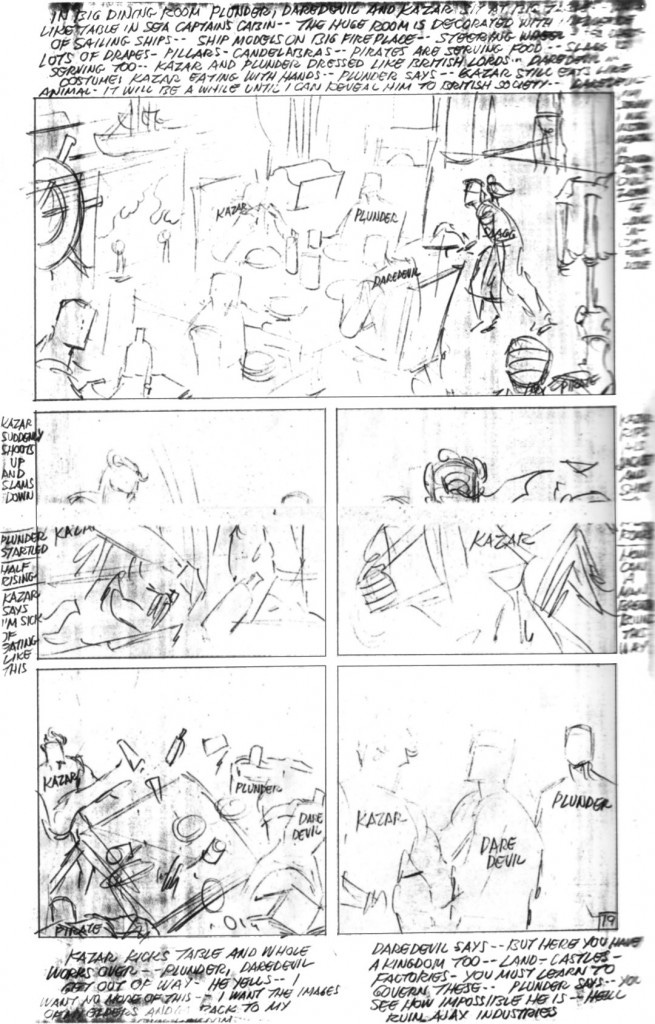

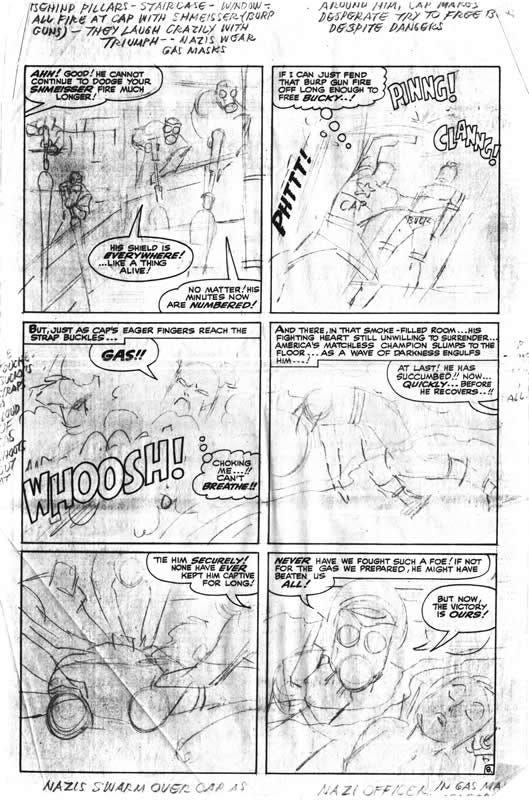

1) THE EARLIEST DAYS

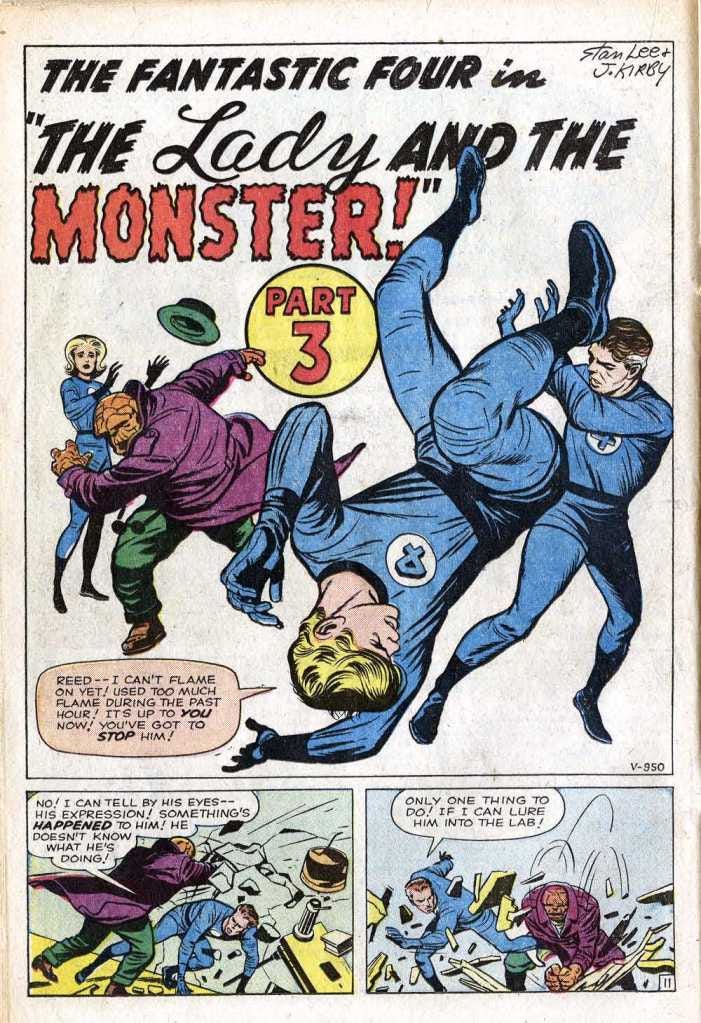

As I’ve covered in depth elsewhere, in the very earliest days of the Marvel books, Lee and Kirby were working more directly hand-in-hand than most realize. Whether that’s because of a greater investment in these stories or their importance to the publishing line, or just micro-managing on the part of editor Lee is unknown. But it’s clear that for at least the first 3 issues of FANTASTIC FOUR, and possibly longer, Lee was intimately involved in the Plotting of the issues–in some cases actively sketching out rough page and panel sequences to sow Kirby what he was after. These sketches were no doubt done in meetings between the two creators, and so they don’t necessarily reflect Lee’s ideas alone, but rather what was being discussed by both men as they worked on the issues.

There’s a point that should be made here by way of comparison. Over at DC, the editor was typically intimately involved in the plotting of the stories. It was routine for an editor such as Julie Schwartz to meet with his regular writers to brainstorm a story for an upcoming issue, working out the overall Plot and the various twists and complications before sending the writer home to write the Full Script that an artist would then illustrate. (Often, many of these stories were based on an already-determined cover image that had to be worked into the story being developed.) The point here being that Lee, as editor, was fulfilling a similar role here at Marvel–but with one key difference. As opposed to DC, where Full Scripts were generated before a story was drawn, at Marvel the artists worked directly from the Plot (and often from less). But Lee would write the Script once the pages were drawn, something that Schwartz and his fellows weren’t involved with, and didn’t get paid for. For pretty much the entirety of their working relationship. Lee wrote the Script for every story he and Kirby worked on together, with only a handful of exceptions.

A digression: many people speaking about this period talk about how Lee chiseled his artists by keeping the Plot money for himself. This isn’t entirely accurate, at least on the face of things. In point of fact, there was no provision in Marvel’s accounting systems of this period to pay for Plotting–it wasn’t considered a separate discipline at all. Writing was defined, in essence, as putting the words in the balloons, and the sum total of any writing payment was made to whoever did that. In instances where somebody was credited with the Plot–as Lee often was on stories written by Larry Lieber, and as Steve Ditko was on his final year of stories, this credit didn’t come with any additional payment (or if more money was provided, it was folded into the rate already being paid for drawing.) This didn’t change until Roy Thomas became Marvel’s editor in the early 1970s (or slightly before–this shift may have happened in the final days of Lee’s tenure as editor, recollections differ) when a decision was made to pay a flat $25.00 for a Plot (deducted from the total money to be paid for the Script.) This amount was increased to a flat $50.00 by the end of the 1970s. When Jim Shooter came in as Marvel’s EIC, he overhauled the system, making the payment split 1/3 for Plot and 2/3 for Script. And it wasn’t until Tom DeFalco became Editor in Chief that the payment standardized at 1/2 for Plot and 1/2 for Script. In any event, the point as it relates to this conversation is that nobody was getting a separate payment for the Plot in the 1960s–something that Kirby rightly took issue with.

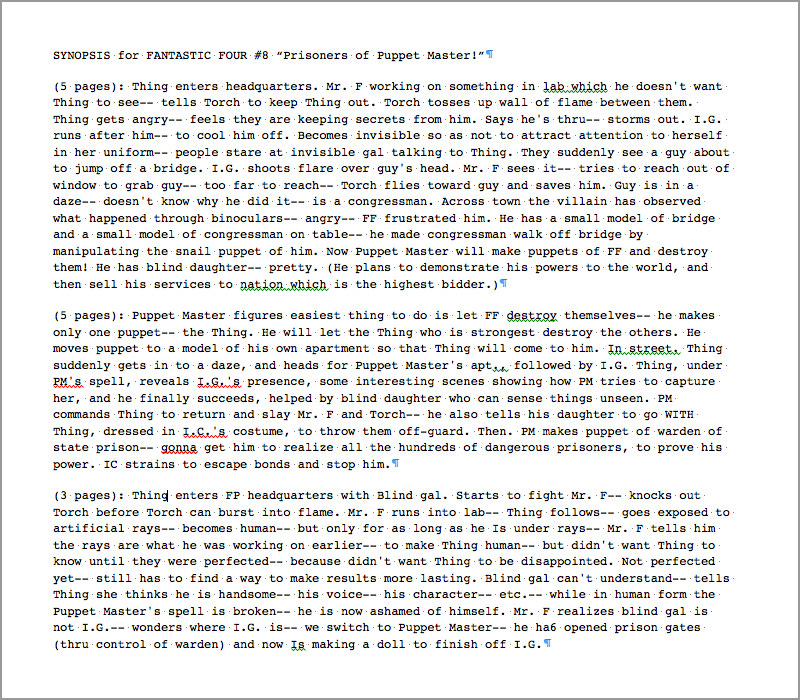

How long did this more direct method of plotting out the stories go on between Lee and Kirby? It’s impossible to tell with any accuracy–but we are provided with one clue. Back in 1962, Lee sent fanzine publisher Dr. Jerry Bails a page of a plot synopsis for FANTASTIC FOUR #8, which Bails then reprinted. It is a very accurate broad summation of the events of the opening half of FANTASTIC FOUR #8, though the printed comic diverges from this synopsis in a number of ways. There is nothing that indicates that Lee generated this synopsis on his own, and in fact my reading of it seems to indicate that it’s an organized summation of a conversation that Lee and Kirby have had as to the events that will play out in the next story. In other words, this is a continuation of the methodology of the earliest issues of the title, where Lee and Kirby were working very much hand-in-hand in breaking down the stories.

The difficulty with this method is, of course, that it takes time. Kirby had to come into the offices to have a conversation with Lee before a given issue could be started upon. It’s also worth mentioning that Kirby’s interests creatively were as a storyteller. He was an artist, true, but that artwork was always in the service of telling a story that he wanted to communicate. In point of fact, Kirby got into trouble with his DC editors in the late 1950s for changing the stories he was working on–even if he might be making them better. At DC in that period, the editors exercised absolute authority over the work, and they didn’t approve of any blurring of the lines: the job of an artist was to draw, not to write. So at Marvel, Kirby relished the freedom to be able to do what he wanted to do, tell stories–at least at first. Lee, on the other hand, was never all that interested or invested in Plotting. For him, the portion of the job that he enjoyed the most, and where he thought he made the greatest impact, was in Scripting the final copy. And so, as Marvel began to expand into additional super hero titles and Lee and Kirby became more conversant with one another, their working methodology evolved into its second iteration.

2. THE SECOND PERIOD

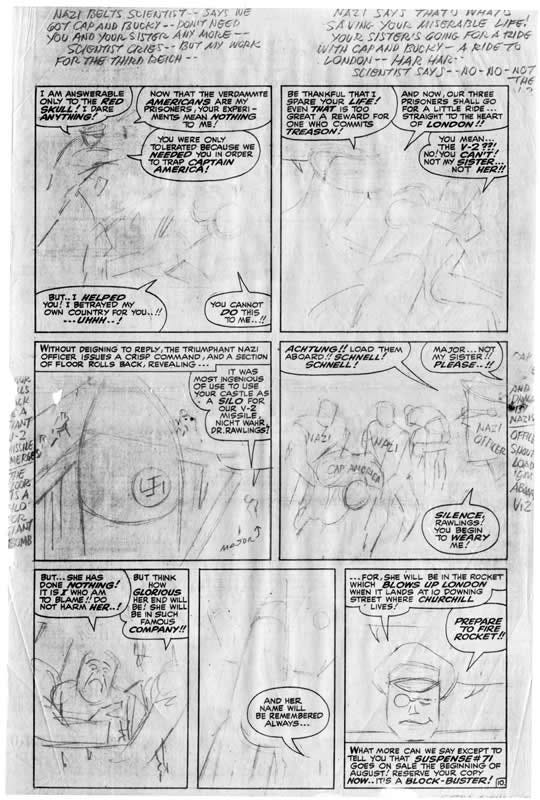

Beginning in late 1962, Lee ceded greater and greater autonomy to Kirby in terms of Plotting the stories they worked on together. While they would still discuss aspects of what a particular issue was going to be about, these conversations would be less involved than they had been, less focused on the minutiae of what might go on on every chapter, page or panel. Simple enough that they could mostly be done over the phone. Once a broad theme was agreed upon, Lee left it to Kirby to Plot the stories as he drew them. Lee would Script the finished penciled pages and also edit and ask for changes or adjustments in anything he didn’t think was working properly at this stage.

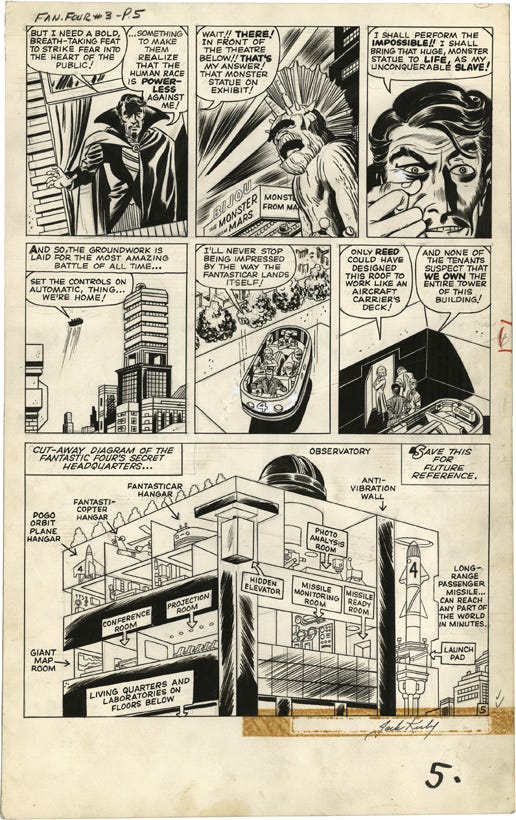

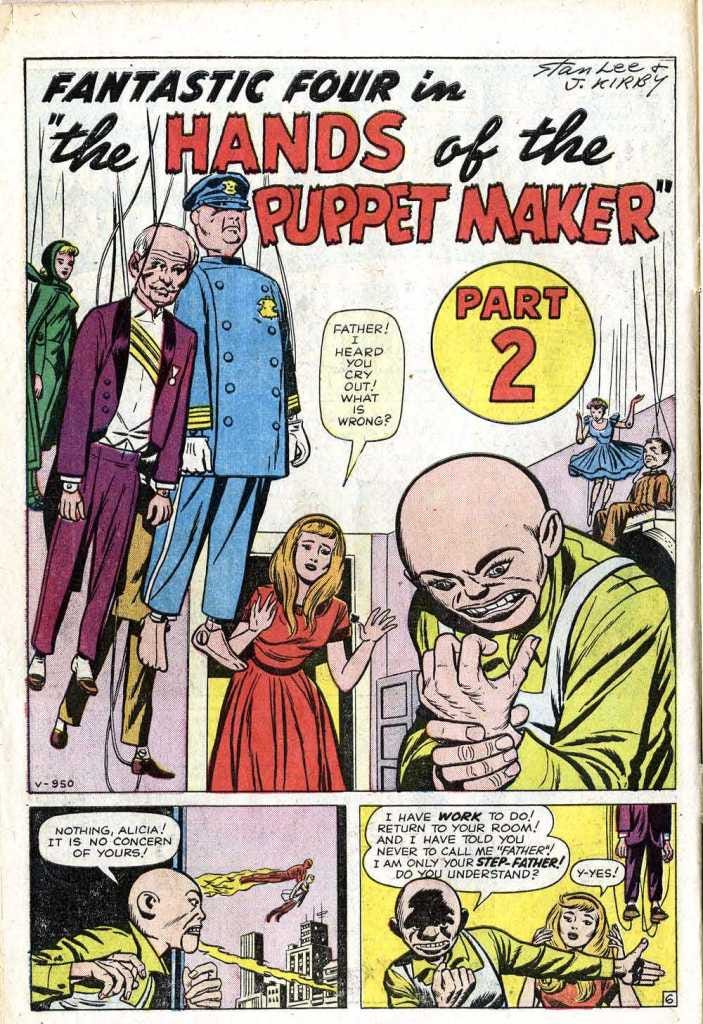

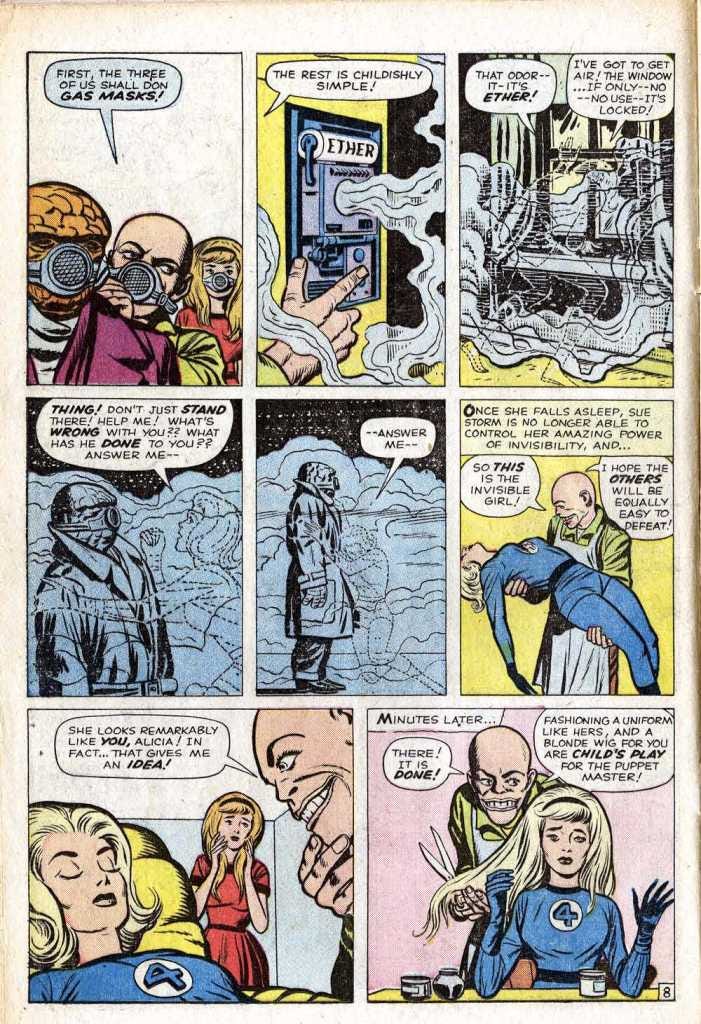

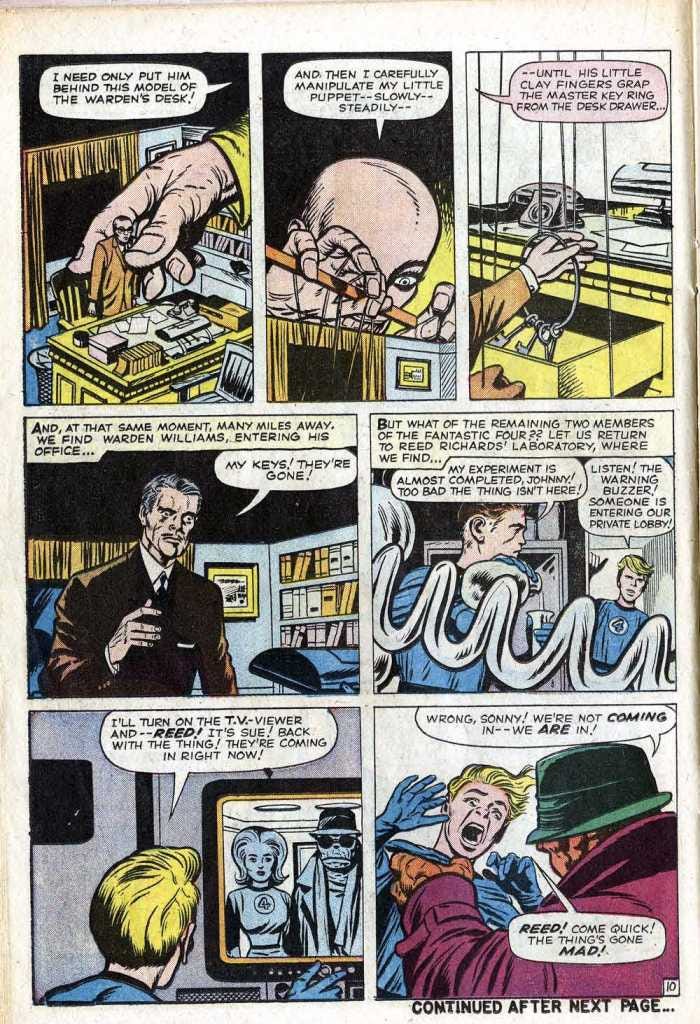

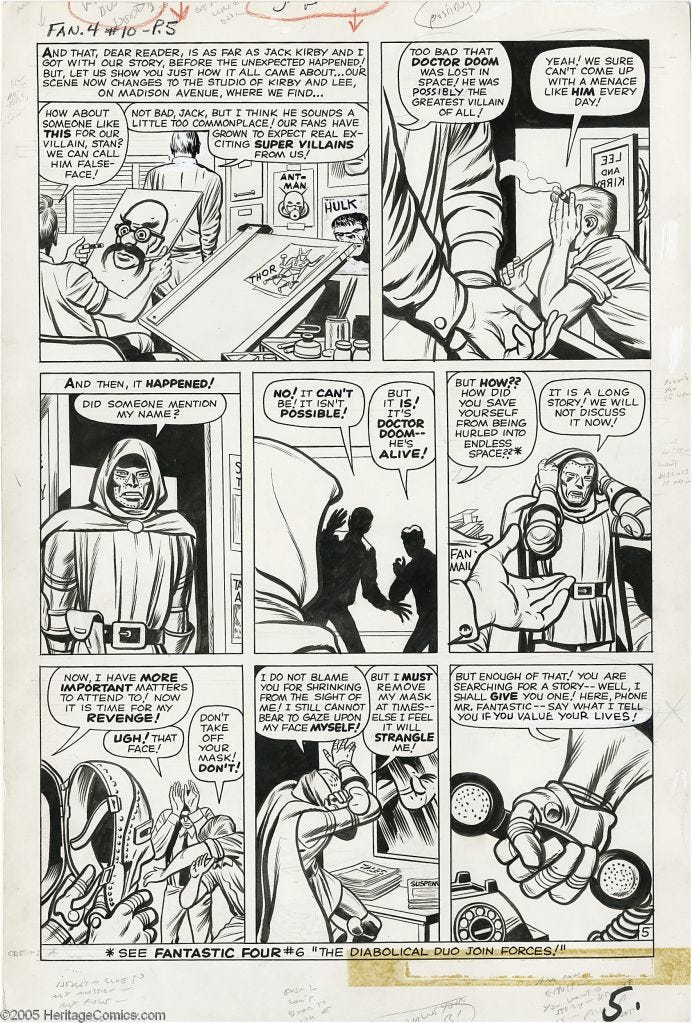

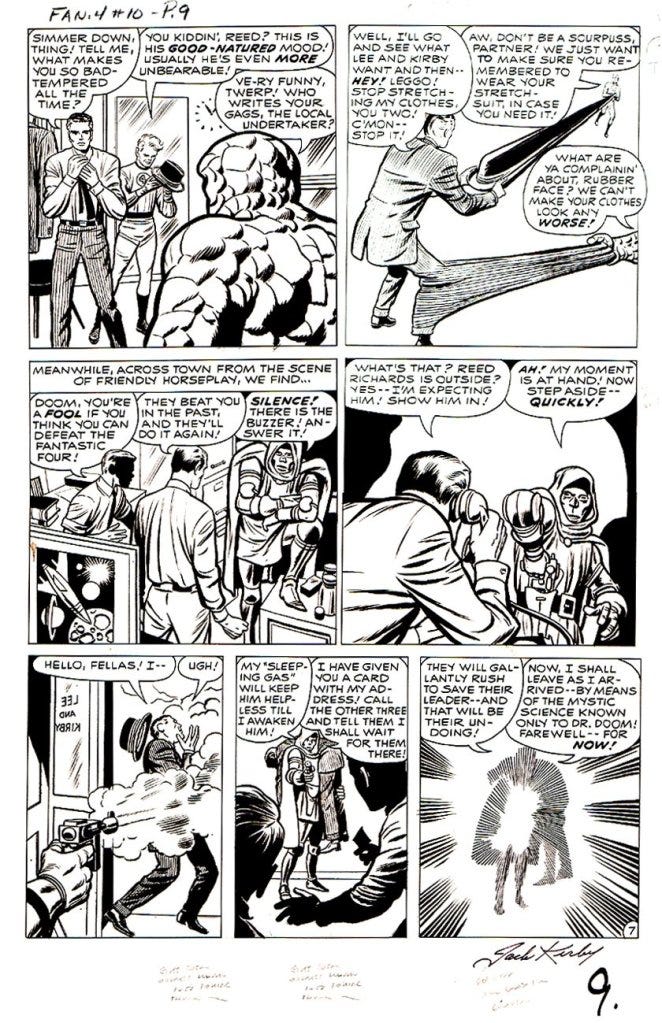

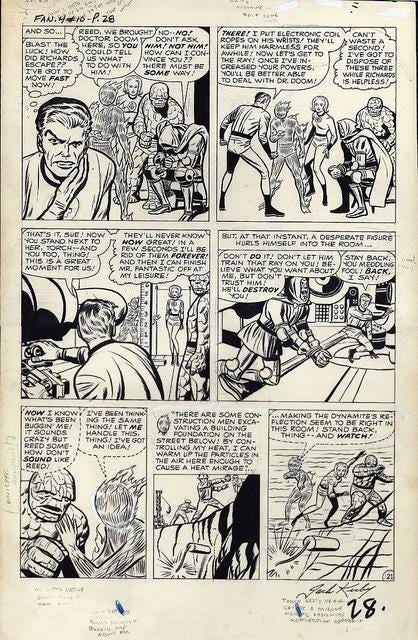

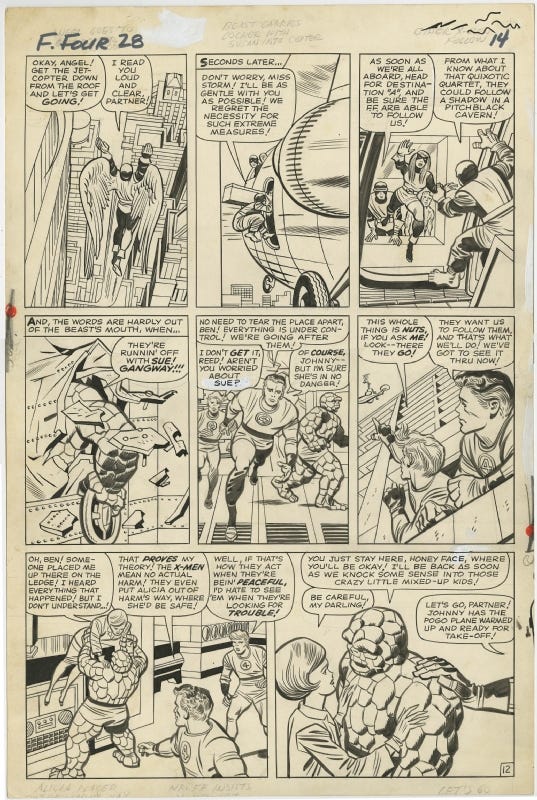

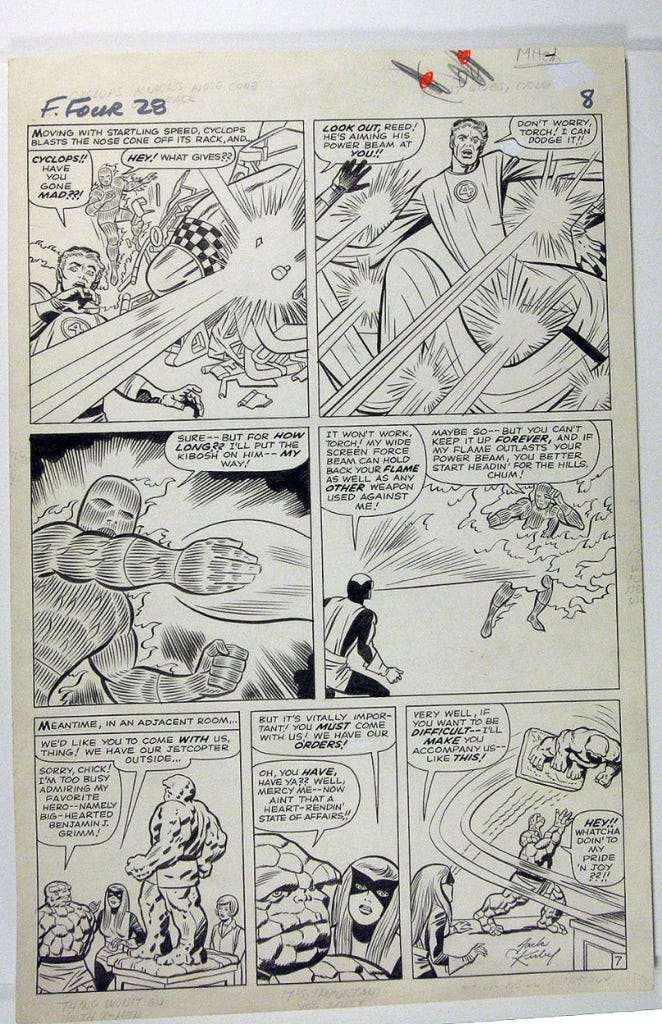

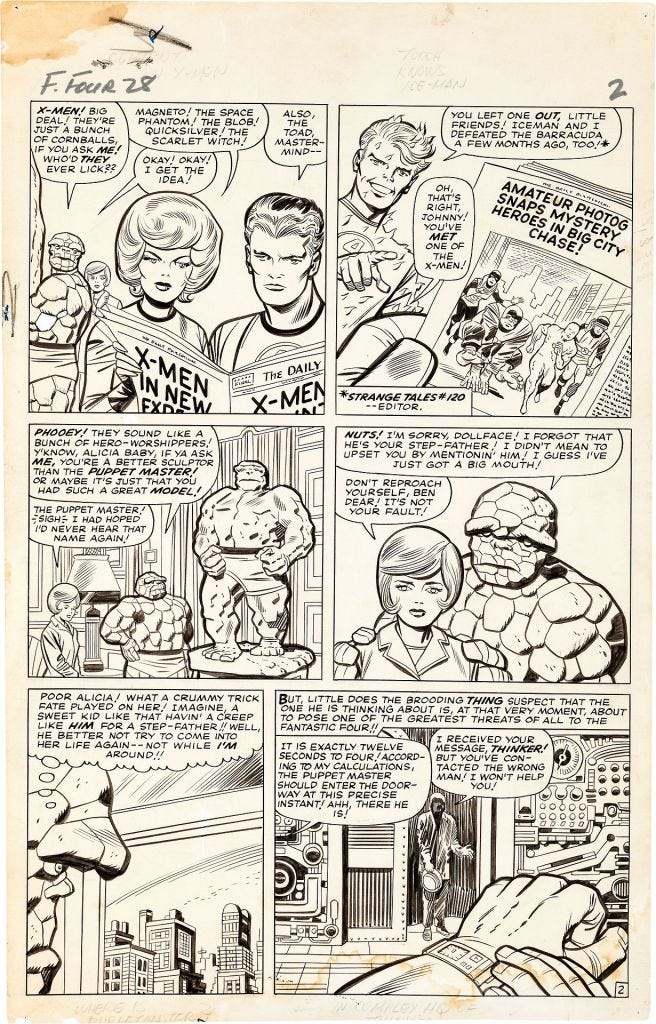

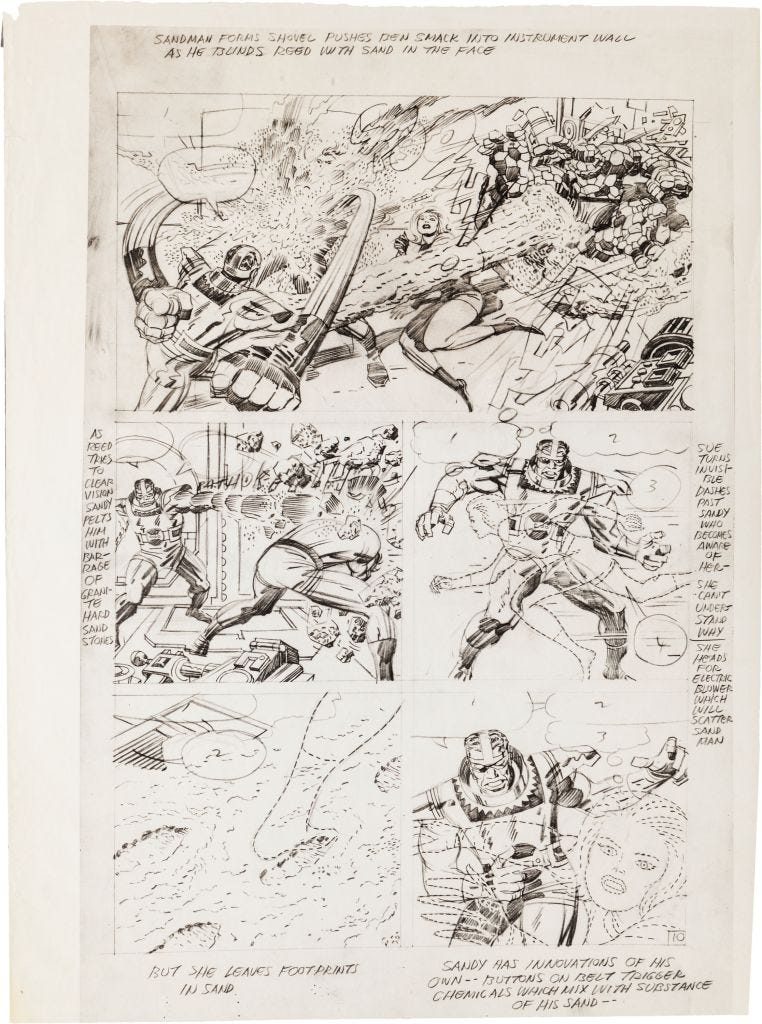

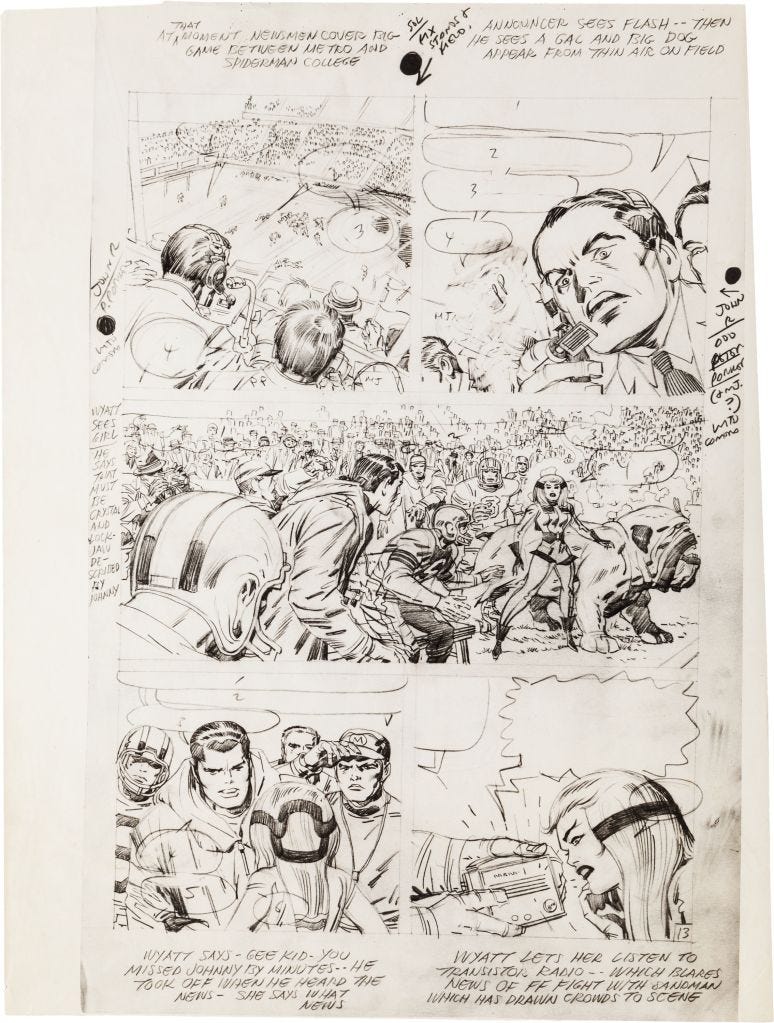

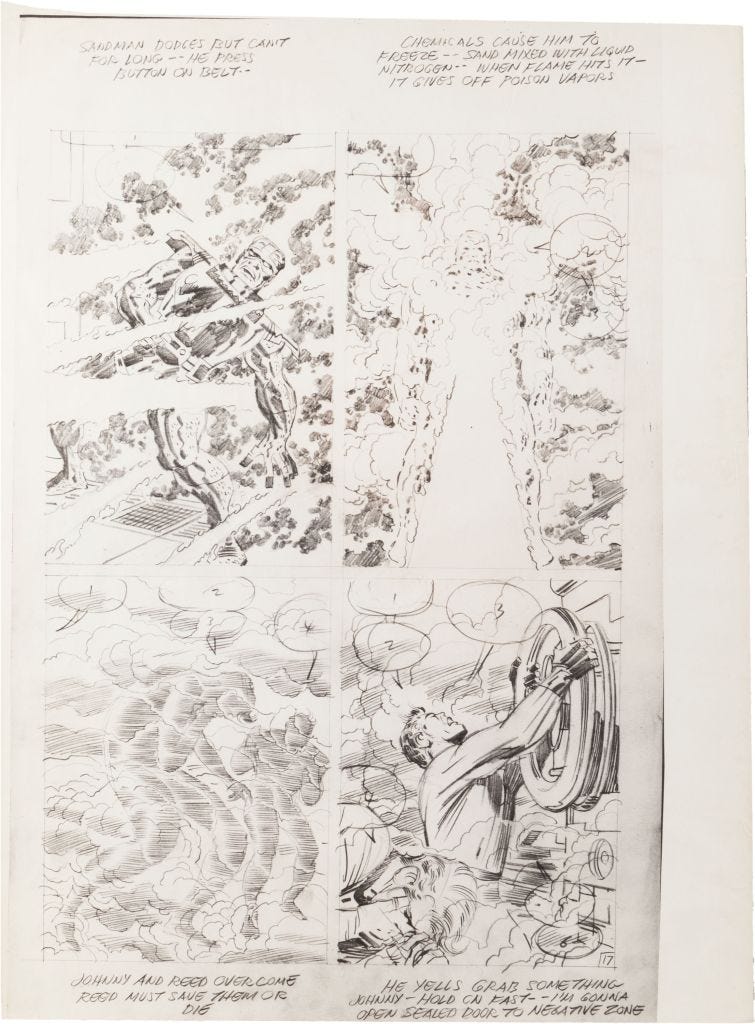

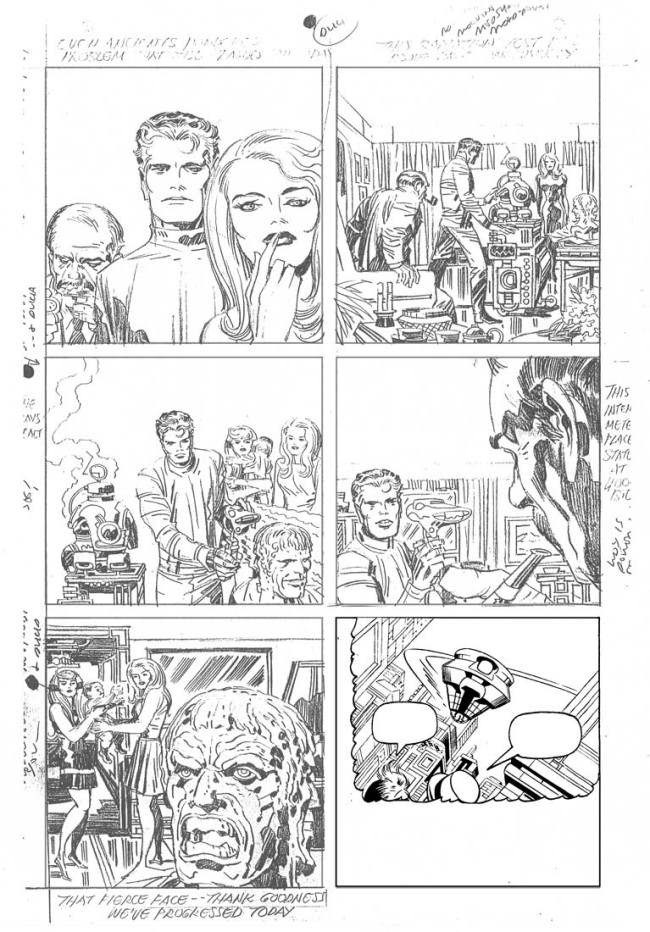

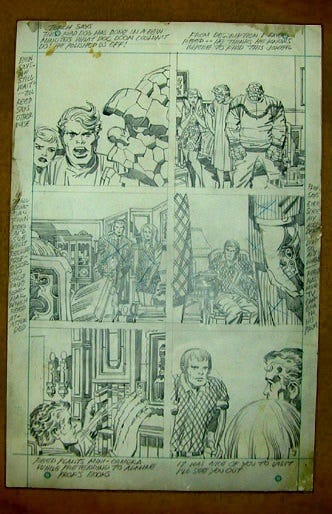

On a weekly basis, Kirby would come into the offices and meet with Lee to walk him through the pages that he had drawn over the preceding work week. As they went over the boards, Lee would scribble notes to himself based upon what Kirby was describing to him, as reminders to himself for when he was Scripting the issue. These notes, in Lee’s handwriting, can be found on the original artwork for many of the stories from this period. Not every page or panel has them–it seems as though Lee only took note of something when it wasn’t readily apparent in the artwork itself.

3. THE THIRD PERIOD

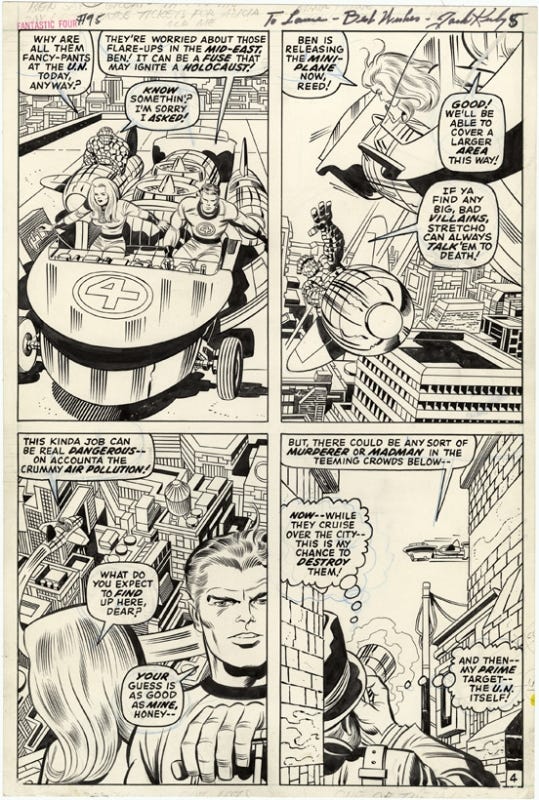

By 1964, though, even those weekly trips into the city were impacting on Kirby’s productivity and his ability to earn a living. Coming into the city meant a day away from the drawing board, which meant that Kirby wasn’t earning during that time, since he was paid on a per page basis. So at a certain point, either Kirby or Lee suggested that, rather than coming in once a week, Kirby instead write his own border notes to Lee outside of the print margins of the pages, describing the events of the story so that Lee could understand what he had in mind.

This process is what remained in place throughout the rest of Kirby’s tenure with the firm during the 1960s, and it ceded even greater control of the stories and storytelling over to him. But not absolute control–Lee still functioned as the both the editor and the Scripter, and in those roles, he would sometimes redirect Kirby’s efforts, and sometimes change the intent of a scene or even a whole story in the manner in which he approached Scripting it. As Marvel saw greater success and expanded the line, Lee would often turn to Kirby to help indoctrinate new artists in how to do comics his way. But after a while, Kirby refused to do layouts for other artists any longer, because he was getting paid only a nominal fee for the basic layout artwork and really nothing for the Plotting that he was doing on these stories for others.

THE FOURTH PERIOD

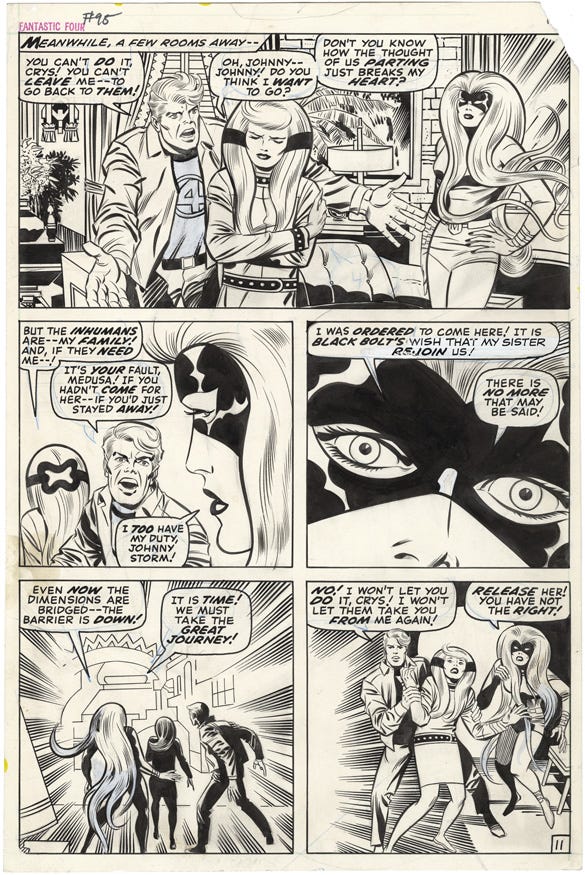

In 1969, Kirby and his family relocated to California, making him the first Marvel artist to regularly work remotely and to mail in his work from a distance. This didn’t change the process too much from the time just before this, but what it did do was insure that Kirby and Lee would seldom ever be in the same room together during the end of their collaboration. All of their dealings from this point forward would be over the phone.

To make matters worse, by this point Kirby was actively looking to leave Marvel, and he’d made the conscious decision not to create new characters for the organization. Especially in their last year together, Kirby was also more insistent that Lee provide him with story plots since he was being credited and paid as the writer. (For a few years, the credits on their joint stories had most often been changed to the more indistinct A STAN LEE/JACK KIRBY PRODUCTION, but most readers assumed that Lee was doing all of the Plotting as well as the Scripting.) It’s impossible to say which stories in that late period might have originated from either man, but it’s overall a relatively slight period–made worse by Marvel’s corporate decision to do away with continued stories, something they had gotten a lot of complaints about from readers who couldn’t always find the next issue on the stands.

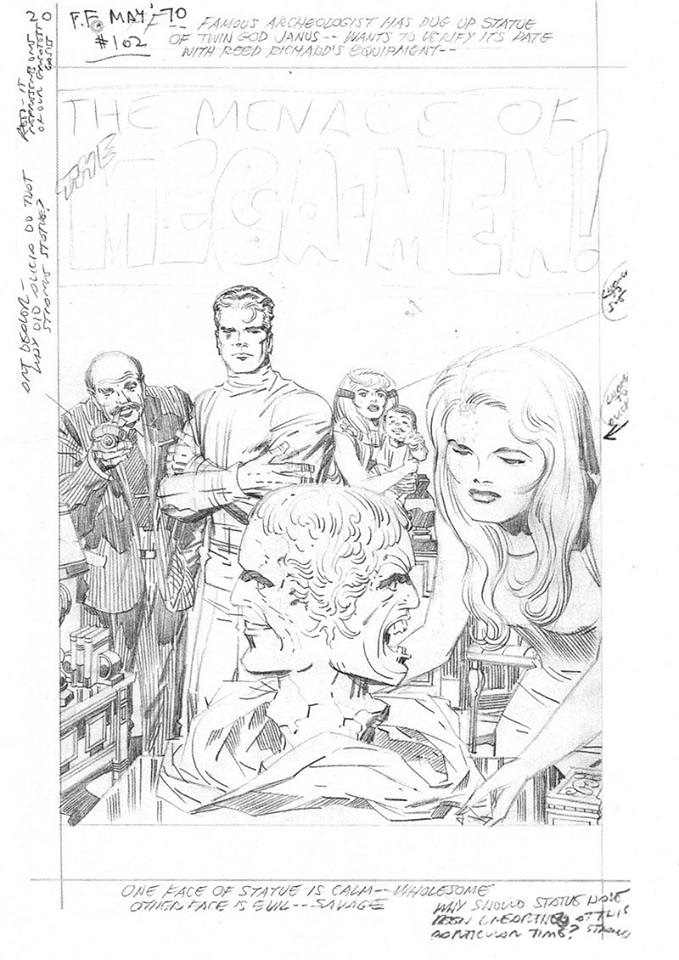

The story intended for FANTASTIC FOUR #102 was apparently one such Lee concept. But after Kirby drew the issue, Lee decided that what he had done didn’t work, and the whole thing was put aside–the story drawn for #103 wound up running in #102, Kirby’s final issue on the series. Having worked on the latter day reconstruction of this lost issue of FANTASTIC FOUR, I can attest to the fact that the story intended for #102 doesn’t really hold together all that well, for all that it has some interesting sequences in it. But you can see that, at this point, Lee and Kirby weren’t really communicating with one another at all, even when they were talking, and so Kirby’s departure was inevitable at that point. For what it’s worth, I don’t for a moment believe that Lee held that story back in order to release it in the same month as Kirby’s first DC books. Rather, I believe reworking it into most of issue #108 represented using up inventory that had already been paid for. The reworked version of the story in #108 isn’t really much good either.

Wonderful dissection of their work process! It fits well with what I’ve learned, over the years, about their process, as well as what it was like when I got my chance to work with Stan, late in the game. I’ve worked plot-style, full script, and about a dozen versions of a mix of both, all of them rewarding in their own ways. What I’m encouraged about overall is to see how Kirby evolved as an artist into a plotter, into a full storyteller. I’ve been trying to emulate his process into my own work. Inspiring!

Thank you SO much for this article! Looking at these pages, to me, is like looking at the pages of the apocrypha!👍🏾🤘🏾✊🏾❤️