Here’s another piece repurposed from The Tom Brevoort Experience. It remains one of the more popular and heavily-read pieces that I’ve done over there. But it’s several years old, so most casual visitors aren’t going to simply stumble upon it easily. So I figured I’d share it with all of you newcomers to this page who may not have experienced it before. As last time, this won’t supercede a new post going up this weekend.

The Purpose of Super Heroes

I've been thinking about this for a while now, pointed in this direction by having watched TOKUSATSU GAGAGA, where they make this sentiment overt: what is the purpose of super hero stories?

On the surface, it would seem to be obvious. Like any other story, the primary purpose is to entertain. But with super hero stories, like it or not, over the past 80 years another purpose emerged. For decades now, super hero stories were a way in which certain values were imparted to their almost-exclusively young readership. Super heroes traditionally embody and even define those attributes which we as a society deem to be the most admirable.

Part of this was defensive on the part of the publishers. When the super hero boom first hit in the late 1930s in the wake of Superman's phenomenal success, the template that most of those coming into the field used in creating their super hero stories was the Pulps, in particular the Hero Pulps of the 1930s. But very quickly, the money-men behind the comics realized their error. Because the Pulps were written for an ostensibly older audience, and so many of their heroic characters--the Shadow comes to mind, but there are dozens more--thought nothing about gunning down a criminal in the most violent and visceral manner possible. In fact, that sense of divine justice was part of the appeal (and still is, in many ways.)

This all kind of came to a head this past week when director Zack Snyder made some derogatory comments about moviegoers who couldn't handle the fact that his versions of Superman and Batman kill people. Putting aside that the manner in which Snyder made his remarks was insulting and belittling, I do wonder if on some level he has a point. Because as these characters move forward and pass from medium to medium, the rules seem to change. I'm not here to get into the question of whether Snyder's super hero movies are any good at all--I haven't liked a one of them, but plenty of other people have, and feel strongly about it. Rather, I want to spend a little bit of time dissecting the underlying question here.

Back when he was Marvel's President and Publisher, Bill Jemas once described the "Thou Shalt Not Kill" attitude of most comic book super heroes as "kindergarten morality" without any tangible relationship to the world that adults (and presumably adult readers) find themselves grappling with each and every day. He thought that super hero stories were a perfect vehicle to communicate ideas and ideals to other people, which is why projects such as the 9-11 HEROES book and the 411 project were done. He just didn't have any truck with the previous century's definition of what made for an appropriate message.

So, should super heroes kill? And beyond that, should they as a rule embody any particular heroic attribute at all? And as we move into new vistas, what responsibility, if any, do we owe to those whose perception of these characters was shaped by the past?

I think this is all especially relevant in a world in which so many super heroes are making the transition to film. And this has always been a difficulty with that translation. Because the ground rules for what defines a hero in cinema have always been different, as a byproduct of the fact that most films are made with an adult audience in mind. So James Bond kills, Indiana Jones Kills, Luke Skywalker kills. Han Solo even shoots first sometimes, no worries about it needing to be self-defense. And yet, all of them are clearly seen and accepted as the heroes of their own universes. So the qualities that make them heroes don't stop at the point where there is a need to take human life. Or, if we're being honest about it, a desire.

Because one aspect of the action movie genre is the revenge fantasy, and it's been a very potent and popular sub-genre for a very long time. In essence, it's not enough for the good guy to take down the bad guy, we want to see the bad guy get his, we want karmic justice for all of the awful things that he's done all throughout the movie. We want to live in a just universe, and in a just universe the bad guy is going to pay with his life, preferably painfully, preferably at the hands of the good guy, our avatar. The catharsis of that moment is a key feature of action-adventure films. It's practically baked into them.

And this has presented problems for the adaptation of super hero properties to the medium of film for decades. BATMAN BEGINS, for example, stops the action of the climax dead so that Batman can turn to the audience and "lawyer" his was out of saving Ra's Al Ghul from certain death--and it's a weirdly deft attempt, trying to make it simultaneously apparent that, for the heroes-don't-kill faction, Batman isn't killing his enemy, but for the revenge-fantasy-catharsis crowd, this is clearly his doing.

Going back to the earliest comic book adaptations, this dichotomy is immediately apparent. In THE ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL, the Republic serial that first brought the character to the screen, Captain Marvel is an absolute lunatic, a far cry from the jovial "Big Red Cheese" we're used to. In the very first episode, he machine guns a horde of fleeing enemies in the back, mowing them down without any remorse. And for the next 12 blood-soaked chapters, he dispatches the bad guys with alacrity, often throwing them off the top of building and or dams and watching them fall, screaming, to their deaths. But by the rules of engagement in this arena, this behavior is okay. He's still the hero because they're the bad guys and they deserve what they get.

I know that, for myself, there's a discordant moment in CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST AVENGER that registers as wrong every time I watch it. And that's the moment, depicted above, where Cap, alongside the Howling Commandos, bursts into a Hydra outpost, guns blazing. Now, on the surface of things, there really isn't anything wrong with this intellectually. It's World War II and Cap is a soldier--he's not only going to be trained in the use of firearms, he's going to be expected to use them. But that depiction is not in keeping with what I want from the character (and, in fact, isn't even in keeping with the rest of the movie. It's the one time Cap is seen firing a gun in that film, and it feels to me--with no particular insider knowledge--like a sequence that was shot with the Trailer in mind, because there had to be some concern that a character as nakedly patriotic and virtuous as Captain America would be a hard sell to movie audiences. This scene shows you that he's a total badass in the language of cinema.) And for me, it's a question of context as much as anything else. I don't have the same reaction, for example, in the first AVENGERS film where Cap at one point picks up a discarded energy rifle and starts to go to town with it. It may be that the difference here is the fact that the second instance has a layer of fantasy over it, where the first one carries the verisimilitude of reality. It's a real gun that Cap is firing at people in that case.

And I think this is all becoming a slippery slope, particularly in a world in which the two major American super hero publishers, Marvel and DC, simultaneously want their characters to be wholesome enough to appeal to a kid audience (and safe enough that the parents of those kids feel comfortable in indulging their children) while at the same time wanting to deal with themes and situations and conflicts that are not so cut-and-dried, creating differing shades of gray for the heroes.

And I do feel like there's a bit of an uphill battle going on even among the people creating these stories. More often than I'd like, we see stories in which the folks behind them have forgotten to make their lead characters heroic, to show them saving or helping the less-fortunate or less-able, to have them exhibiting self-sacrifice. This was one of the recurring mantras of Spider-Man editor Steve Wacker: Can we have the good guys saving somebody, rescuing people, and not just fighting with one another?

I don't think it's a question of killing or not killing per se. I think it's a matter of context. A few years ago, there was a Wolverine story published, and after it came out, I went over and gave the editor an earful because it violated this tenant. In the story, Wolverine finds himself in the Savage Land, where he happens across several SHIELD agents carrying an unconscious Shanna the She-Devil away. leaping from cover, Wolverine proceeds to slice and dice the SHIELD guys. Now, it turns out ultimately that these guys aren't actually SHIELD Agents at all, they're impostors--but at this point in the story, Wolverine doesn't know that. And so, from my point of view, he jumps out and kills a half-dozen law officers who are simply doing their job. No context, no conflict. But visceral. And satisfying. That moment lost me in that Wolverine story because I could no longer relate to him as the hero. He was as bad if not worse than the guys he was fighting, killing people for the hell of it because he just knew better. The fact that the story let him of the hook ultimately doesn't change the fact that the writer messed up--he was relying too much on the fact that readers are already invested in Wolverine as the hero so they're likely to go along with his actions and be sympathetic to his point of view.

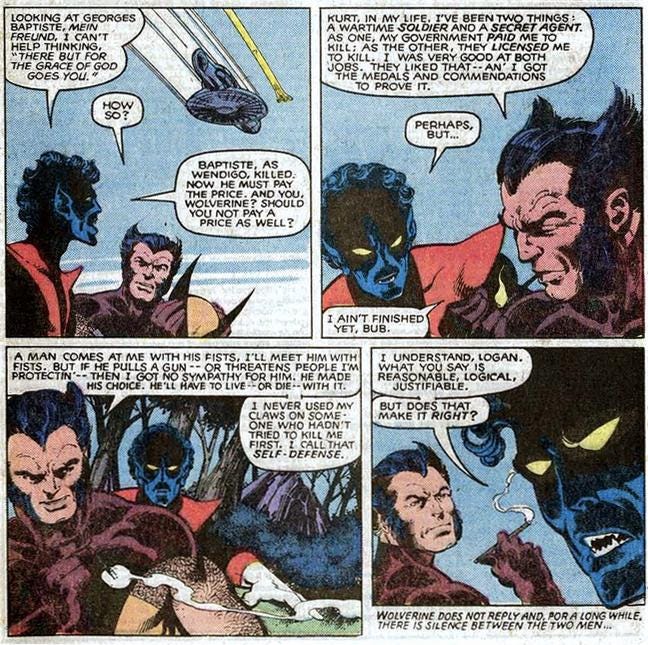

To me, Wolverine always comes back to an exchange that Chris Claremont and John Byrne presented in UNCANNY X-MEN #140. Here, Nightcrawler questions Wolverine's methodology, how free he is about using his claws, how much he seems to enjoy it. And he asks what gives Wolverine the right? And Wolverine says that, in the past, he's been both a soldier and a secret agent, highly decorated in both professions for his ability to kill. But if a man comes at him with his fists, he'll meet him with fists. It's only if he pulls a weapon or threatens somebody Wolverine is protecting--if the aggressor initiates deadly force--where Wolverine will do whatever it takes to put them down. Future writers--including Claremont and Byrne themselves--sometimes seem to struggle with this idea, but it's that simple code that allows us to accept Wolverine as a hero and not just another murderous killer. (And even then, in that original story, Nightcrawler isn't convinced by Wolverine's rationalizations for his behavior--he believes in a higher morality.)

I do think that super hero creators in all mediums have a responsibility to their audience, regardless of its age, to give thought to their presentation. It's not as simple as merely kill-or-don't-kill, and what works for one character won't necessarily work for them all. But it is about presenting the moral code that a particular character possesses and then operating legitimately within the confines of that code. And if a character violates his own set of ethics, we should see and feel the result of that as well. It's also worth understanding that, especially when talking about the most iconic super heroic characters, these figures have been around long enough to have become enshrined in the hearts and minds of audiences. They stand for something, even if their particular morality is the byproduct of another time and another era. And so we need to be thoughtful about how and what we update to reflect the times that we are in, and what aspects make the characters who they are. Because the purpose of super heroes is to tell us who we are, and what we value, in an idealized world.

"A man comes at me with his fists, I'll meet him with fists. A man stands guard at a gate I want to go through, holding a wooden spear, making some Savage Land bucks to support his Savage Land wife and kids, I'll slaughter him like livestock before he even knows I'm there."

Quite honestly, this was a problem I always had with HARLEY QUINN— a character I enjoy immensely and enjoyed writing immensely, but the fact was she had killed many, MANY people, and had no remorse over it. In her defense— and I did make it just that in the comics I wrote— she is insane. When it came time to do my and David Hahn's creator-owned IMPOSSIBLE JONES, I made it very clear she was a THIEF— not an assassin, not insane— the implication being she stole things without necessarily killing people. Which doesn't mean she's an angel— she certainly has no problem LETTING people die who are trying to do her harm. I think IMP can be HEROIC, but she is not necessarily always a HERO.

The other side of this conundrum is the idea of the BULLY. Most superheroes, almost by definition, have something going for them (powers, skills) that the normal person does not. So (to my mind) you have to be very careful how those powers and skills are used. Captain America against a half dozen armed goons (or soldiers) is still a lopsided battle. We all want to cheer for Might Makes Right— when that might is on our side— but we have to be very careful about the message that sends. Call me crazy, but I think a lot of the problems we have with gun violence and political extremism in this country right now is because far too many people think LIFE IS LIKE THE MOVIES. And the more superheroes populate that movie mainstream, the more it's essential to be very aware of the message they're sending.