#23: Chasing the Dragon

You Know You're Just Another Addict Looking For A Fix

Being a long-time comic book reader is more than a bit like being a junkie. You start out, you take that first hit, come across your first comic book, and you begin to get hooked. And then, soon, within the first couple usually, you hit a particular story that completely melts your brain. A book that you’ll return to again and again, a particular endorphin high that’s difficult to replicate, since so much of the closure of reading coming books happens within your own mind. It may not be the best comic book story you’ll ever read, but it is the one that sets you off on a dedicated journey to find more like it. And that, over time, can be where the problem comes in. Because like any drug, if you use it often enough, if you read a ton of comics, the impact, the effectiveness of each individual one lessens. You still get an endorphin hit, but it’s rarely at the same level as those initial ones that made you a regular devotee of the medium. Sometimes, this sense of disappointment can manifest itself outwardly, in the person of fans who are unhappy with the direction of certain titles or the efforts of particular creators. Which isn’t to say that criticism isn’t valid—it certainly can be. But part of the difficulty over time is that it takes more and more to achieve the same high that got you hooked in the first place. I know for myself, I love that hit of a perfectly excellent comic book. And I also read an awful lot of material looking for that hit. And at this point, having done this as an audience member for close to 50 years, I find that the contents of the average random comic book I might pick up and read for pleasure doesn’t stick with me for very long. There are times when I’ll read a stack of books on a Sunday, and if on Monday I’m asked what I read it can be difficult to recall. So those highs become few and far between. But when you get one, whoa boy! In drug culture, this quest for that elusive high that takes you back to when you started was once called “Chasing the Dragon”, and it led any number of people to overdose and a final, fatal trip. Fortunately, a bad comic book is only going to kill your spirit a little bit. I don’t know that there’s any particular point that I’m driving at here, apart from the fact that it’s an inescapable fact of life that, as one gets older and has experienced more and more material, it becomes more difficult to catch that dragon—hell, even to find that dragon. But I’m still looking, every week, and once in a while, a dragon is sited, and even ridden.

Once again this week we need to give special thanks to the omnipresent writer of nocturnal crimefighters Chip Zdarsky, who not only continues to follow this feature with an almost religious zeal, but who has also made plugging it almost a regular part of his own Newsletter (which you can follow here. Chip gets special points this week for coining the term “Brevortex”, even though he needs to misspell my last name to do so. That’s some Class-A wordplay right there. Working on trademarking it even as we speak.

Despite my seeming vow to keep these things shorter and easier to get through, the system is already telling me that what I’ve got set up here is too long for Gmail. Well, screw you, Gmail—I will not be silenced! So let’s do some Reader Questions to get warmed up. If you’re on Gmail, I’m sorry, you’re likely missing out on all of the best bits.

First up, Matt asks:

Do you ever have concerns, regarding the publishing line as a whole, that if certain books don't feel like an urgent read to you, the readership at large may regard them the same way?

Not really, no. It’s an undeniable fact that there are more comic books being released on a regular basis than any human being could afford to purchase. This is a marked difference from the days of my youth, when, with just a single Pennysaver paper route, I could afford to buy every new comic book that I wanted in a given month, plus have enough scratch left over for back issues. But that all said, as I regularly tell our editors, Not Every Comic Book Is For Every Reader. If everything that we’re doing appeals strongly to me, then we’re doing something wrong—my personal tastes should not be the only barometer. So just because a book doesn’t feel like an urgent read to me doesn’t mean that it won’t feel that way to other folks. And even among the specific books I spoke about in a previous Newsletter that inspired this question, books that I’m likely going to set aside in favor of other fare, an Adam Warren futuristic VENOM THE END story or an Erik Larsen CAPTAIN AMERICA THE END with a hundred Red Skulls seems right up my alley. It’s just that there are a whole lot of other books also vying for my attention, and the stories in those titles aren’t as likely to have any impact on what I’m working on next month. But it doesn’t mean that those stories are without value or appeal.

Alan Russell wonders:

How much nowadays do trade paperback sales factor into a series continuing or being cancelled? Obviously some books are likely down the line to have healthier sales in collected format vs single issues. But how much leeway is given now to see trade sales figures, as some books get canned really quickly now.

This is one of those questions that readers bring up all the time, and it’s one that I’ve answered quite often over the years—none of which is enough to inform new people. And the answer here is that of course the sales of a title in its collected form can have an impact on its longevity. But the caveat to that is the fact that, with rare exception, the titles that sell the best for us as singles are also most often the titles that sell best for us as collected editions—and the books that are weak as singles usually post similar results as collections. There’s an occasional outlier, but the frequent fan conception that there are somewhere thousands of spine-loving bibliophiles just waiting for five issues to be completed and bound so they can descend upon the collected edition like hungry locusts doesn’t usually have a lot of basis in reality. It can happen, sure, but it’s far, far more frequent an event than most people realize.

Sergio Flores inquires:

I’m curious about the comp comics system. If I remember correctly, didn’t Marvel and DC used to send comp copies to each other for a while? How and when did this whole system begin, and when did the comps between companies stop?

Also, I’m curious about licensed characters. How do you weigh the decision of adding a licensed character into the broader Marvel Universe, in-continuity, knowing that there’s a possibility that reprints may be an issue down the road?

The Comp Copy Exchange was a thing worked out and agreed-upon by Marvel and DC at some point in the 1970s. The idea, simply, was that each company would provide the other with a certain number of copies of each of their releases to distribute to their editorial staff in exchange for copies of the other company’s releases. It was a grandfathered gentleman’s agreement for literally decades, made off the back of the fact that many of the editors at each company were hungry to read the new comics when they came out, and to be able to get them in reasonably good condition. Over the years, as cover prices went up and things like MARVEL MASTERWORKS Hardcovers started being produced, certain ceilings were placed on the arrangement—typically coming down to cover price. And at different points, other companies such as Image, Valiant and Malibu made similar arrangements. It wasn’t unheard of back in the early 1990s during the comic book boom for the “bundle” of comp copies each editor received to be almost as tall as they were. The process had been winnowed down somewhat over the years on a number of occasions as one outfit or another looked for cost-cutting measures, but it was always a thing that the key editors who wanted copies fought hard for. But the thing that truly did it in was DC’s migration from New York to the West Coast. At that point, the owners of the company didn’t want all of those comic books cluttering up the offices, and so DC switched all of their editors to receiving digital comps rather than physical copies. For a while, Marvel continued to get DC comps even after DC’s own people didn’t, but if the DC owners didn’t want DC books lying around the place, they definitely didn’t want Marvel books doing the same, and so the whole exchange was eventually shuttered. This only happened a few years ago, though.

As to your second question, these days we tend to make whatever provisions seem prudent when we work out a licensing deal, with an eye towards the future and a knowledge of the diverse forms our material may eventually be released in. But this wasn’t always the case. When you’re talking about the classic licensed properties that have caused problems because of their inclusion within the Marvel Universe—series such as MICRONAUTS, ROM, SHOGUN WARRIORS, GODZILLA or even MASTER OF KUNG FU (which was built as a vehicle for the Sax Rohmer Fu Manchu material) nobody thought that any of this stuff was ever going to be reprinted outside of maybe in comic book form. Trade Paperbacks and Hardcovers and Omnibuses weren’t a thing back then, so nobody thought about it at all when the deals were made. To say nothing of new media formats such as digital. So we now have to deal with the largesse of agreements made in different times. Moving forward, we try to set out the circumstances of who can reprint what stories in what context when—but inevitably, there’ll be some new format in the future that nobody today even dreams of, and today’s agreements will be just as troublesome as yesteryear’s. But that’ll be my grandkids’ problem.

Mister Ray Cornwall asked this question in a few different forums:

What’s the best “last issue” of someone leaving a significant Marvel run? It has to be Peter David’s last Hulk book (at least before he came back a few years later), doesn’t it? As a more recent example, Dan Slott’s last FF book was really good- I think he nailed the ending with the intro to Reed’s other brothers and sisters.

I think this is a good question to throw open to the readership, actually. So please feel free to make your suggestions in the comments. I think, for me, the final issues of a run that seem the most satisfyingly like a conclusion tend to be from the DC camp. Things like Grant Morrison’s final issue of DOOM PATROL or Alan Moore’s last SWAMP THING issue. Heck, the last issue of the original DOOM PATROL, in which the whole team was killed off , was about as apocalyptic and unexpected a conclusion as one could find, especially for that era. But most of the classic long Marvel runs have tended to either end abruptly, often in mid-stride as some creator ran into difficulties and departed (I’m thinking of John Byrne the most here) or else perfectly nice final issues that didn’t completely feel like a conclusion so much as just another issue. A lot of that comes from the fact that the ethos at Marvel for so many years was that each title was just one strand in the larger tapestry of the Marvel Universe, so writers were expected and encouraged to pick up the business of their predecessors and weren’t looking to craft a finale that felt like a finale. Whereas DC, especially the branch that eventually grew into Vertigo, adopted a limited-timeframe model into their approach very early on.

We got a trifecta of questions from Michael Cross:

Was there a great project, for whatever reason you or you/Marvel passed on that went on to be a huge hit somewhere else?

Has there been a title you worked on that went on to be a huge hit, that you weren't sure was going to find initial success? Or one that others doubted, that you were convinced was going to be success and it was? or wasn't?

Are you still "collecting" any particular comic titles or series - I'm working back Amazing Spider-Man and Avengers (40 to go!) for example.

Not really, not exactly. But there were ideas that were pitched to me in a prototypic form that creators later refined and turned into something greater elsewhere. Two examples spring to mind, one of which I’ve mentioned previously; When Fabian Nicieza left NEW WARRIORS, I held an open call for pitches to replace him. One of the ones I received (and directly sought out) was from a new writer whom Marie Javins had brought on to write HELLSTORM, Warren Ellis. As you’d expect, Ellis’s pitch for the series was very well-written. But it was also bold in a way that I wasn’t ready to be yet (he planned to kill off 2/3 of the characters in the first issue as a way of clearing the decks, something I didn’t necessarily want to do.) But buried there in that pitch was a character called Jenny Sparks, a proto-version of the character Warren and Bryan Hitch would later introduce in STORMWATCH/THE AUTHORITY. Along similar lines, while I was working in the Spider-Man office, a young Mark Millar (with whom I’d worked on SKRULL KILL KREW) pitched me a series called SHOCKER in which the young nephew of the Spidey villain would inherit his costume and identity after the villain had died, and would be ushered into the underworld of super-criminals, one with its own rules and mores. But this was right around the time that Marvelcution was about to happen, and that pitch got scuttled in the crossfire. Undaunted, Mark completely rethought a bunch of the notions that he’d had for that book and turned them into WANTED over at Top Cow some years later. So Marvel could have had Jenny Sparks and Wesley Gibson, but neither one would have quite been the character they became under other circumstances.

As far as your second question goes, yes, every version of that. No particular examples readily stand out for me, though. The plain truth of the matter is that, as screenwriter William Goldman said about the filmmaking business, “Nobody Knows Anything.” And that includes me. I wouldn’t pursue a project that I didn’t think had at least the potential for success, and I would argue against moving ahead with any project that I thought did lasting damage to the characters. But in the end, all I have to measure those things are my experience and instincts—and while those instincts have been honed by years of trial and error, nobody ever knows for sure what’s going to hit and what isn’t. To give two recent examples: if you asked me beforehand, I would have predicted that the Christopher Cantwell/Cafu run on IRON MAN would have been better received than it was. Why didn’t it connect with audiences the way I thought? Damned if I know (though there are always a bunch of fans who will give you their theories as “fact”.) On the other hand, I also figured that the Jed MacKay/Alessandro Cappuccio MOON KNIGHT launch would do all right, but not as well as has been proven to be the case. Some of that is down to timing and the interest in the then-approaching Disney+ series, but some of it was also just down to it being the right book at the right time.

And finally, while I still buy the occasional old comic book (typically reading copies these days—I went through a period during the first year of the Pandemic where I bought up copies of assorted random DC 100-Page Super-Spectaculars from the 1970s even if I already owned them, just to have some comic book comfort food around.) But apart from that, years ago, I dropped the most money I’d ever spent on a comic book acquiring something of a grail issue—and once I’d done so, it was like a spell had been broken. I haven’t felt the same urge to buy back issues since then. Which makes going to comic book conventions just a bit more tedious than it had been before.

Okay, one from Nacho Teso:

what kind of resources do editors have to keep track of continuity, apart from receiving the monthly books to read what isn't under their umbrella? Is there any kind of big excel spreadsheet or word document that has loose-ends, plot-points or anything like that?

Not really. Each family office tends to keep a rolling spreadsheet of their own upcoming releases projecting out anywhere from six months to two years ahead of time, as a living document that can change as the situation changes. But at least on the one I use, each month gets deleted from the document once it comes to pass and the titles see print. So there isn’t any simple central repository of knowledge (apart from the Internet, of course) I don’t have an example of one of these right to hand, but I’ll look around for one to show in the near future.

And finally, a final question from Marvel’s Talent Coordinator, Rickey Purdin:

You made mention in your post a few weeks ago during a heads up about the new issue of Moon Knight being on sale of your “small crew of comics-reading friends” calling the character different names. I’d love to hear about your comics-reading friends growing up. Seems like it might be easier these days to find a peer who has read a comic than it used to be. I know I tended to be the comic guy in my groups aside from one cherished exception.

It was never easy in my lifetime to find other like-minded people who read comics. But consequently, most of the people who became my closest friends at any given period in my life tended to enter my orbit through a mutual love of comics. When I first started reading the books in 1973, comic books were still relatively ubiquitous. Almost any household that you’d step into with kids would have a few of them lying around. This is why, in my earliest days, I was able to trade frequently with my next door neighbor Johnny Rantinella, and occasionally other kids such as Charles Grella down the street. But comic books were more important to my life and my imagination than to most, and I stayed monofocused on them all throughout those periods when other kids were moving on to other things. My first real comic book-reading friend was Donald Sims, who I met in fifth grade. Like myself, he didn’t just read comics, he drew his own as well, and that was the thing we bonded over. He had a collection that he’d inherited from some relative that included books dating back to 1972, which is where I first read FOREVER PEOPLE #1 and MISTER MIRACLE #2 and the like. But by the time that we graduated into Junior High School starting in 7th Grade, he’d left them behind and we naturally drifted apart. Before that, though, in my last year of Grade School, I attended a weekly special class for “gifted” students across the school district. No, it wasn’t run by Professor X, but it did bring together the most intelligent students in the district for a curriculum that was a lot more open and thoughtful than the standard. It was the 1970s, after all. There, I met David Steckel, who became a good friend for many years. Dave was a more athletic kid than I was, but he was also a comic book reader and absolutely obsessed with STAR WARS and BATTLESTAR: GALACTICA. When he discovered that I made my own comics, he twisted my arm a bit to get me to draw his homebrew knock-off series, STAR RAIDERS. He too had inherited books from some relative, and we would frequent lend each other comics for reading purposes. It was his copies of the Captain America of the 1950s storyline and the Avengers/Defenders War that I first read. We were united in our mutual love of the Fantastic Four, which led to something of a competition between us that became semi-eventful, but which I’ll need to cover some other time. It was also around this point that I first came into contact with Frank Torres, another comic book reader who had artistic aspirations. Later in life, he became a cop. In Junior High, I shared a couple of classes with a kid who I eventually saw drawing his own comics. I can remember having to work up some way to break the ice and talk to him—I wasn’t the most confident kid in the world at this point. This was Israel Litwack, who likewise became a longtime friend. Israel was a big STAR TREK fan who also exposed me to a wide range of things he liked, including THE SHADOW and MONTY PYTHON and ANDY KAUFMAN. Even after my family relocated to Delaware for my Dad’s job, we stayed in contact—it was Litwack with whom I first saw the 1989 BATMAN movie over the course of my Marvel internship. But I’ve not seen him in many years, he relocated to France, got married and started a family. Litwack was the first person I teamed up with to make comics, as he was a better writer than I was. We circulated xeroxed copies of our super hero comic book ATTACK FORCE both through the comic shop and among the kids in our school. We also both came into contact with Steve Ventura, another local fan whose big favorite character was Thor. Steve had another buddy who often palled around with him, and so wound up in our group a number of times, but whose name escapes me today. And all of us wound up joining a comic book club that was advertised in our then-local store, Port Comics. It was run by Glenn Hauman, who today is perhaps best known for being sued by Paramount over his Dr Seuss-inspired parody STAR TREK book “Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go!” (Glenn was just a little squirt when I first met him, though he is freakishly tall today.) Through Glenn’s club, I came into contact with a number of other fans in the general area, including Jeff Kellner, who was also an amateur moviemaker, and who loved Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Anyway, once my family’d moved to Delaware, we lived in a new development that was only just being built up. Consequently, until I became old enough to drive, I was cut off from most other people—there was no one and nothing around within easy traveling distance. The one real exception was Steve Cicala, whom I met at a cartooning class being taught by perpetually harried University of Delaware student Dennis Daub. We drove him nuts on a regular basis. Cicala was a super-sharp, super-creative guy, and I fell into a steady two-hander arrangement with him for several years, until he went away to art school out of state. It would have been Steve with whom I did riffs on Moon Knight, giving the Moon Guy/Moon Goon character dopey identities like Steven Slant and Shmake Shmockley. Like Litwack, I haven’t seen Cicala in decades—he relocated to New Zealand for a job after graduating and stayed there, getting married along the way. He still follows my Twitter feed, though. It was during this period that I became a fan of STAR BLAZERS, the Americanization of the Japanese anime SPACE BATTLESHIP YAMATO. Because it played in the area for years, Cicala was a devotee of the show as well, and this led us to make contact with the dawning anime fandom that was building up around the series, spearheaded by people such as Michael Pinto, Brian Cirulnick, Derek Wakefield, Jeff Blend, Doug Peacock and many, many others. But the guys we were the most simpatico with in the crowd were the group nicknamed “The Bostonians” since they all lived in the Massachusetts area; Frank Strom, Mike Kanterovich, Dan Parmenter and a few other hangers on. They were creative in much the same way we were, read and watched the same stuff, and made their own comics with some asperations of making it a career. And so I would spend literally hours on the phone with them. Seriously, it was not unheard of for me to call up Mike or Frank at around 9:30 in the evening and still be on the phone with them as the sun came up. We had a bit of a ritual where every Friday, the day when new comics came out in those days, we’d buy and read the books during the day, then talk about them and dissect them in marathon round-robin phone calls all night. I spent a whole lot of money on phone bills in those days. More locally, I would hang out with my good friend the late Clarence Woodlyn, with whom I worked fast food throughout college and who was also a comic book reader. We’d occasionally be joined by Jon Getcheau, a friend of Cicala’s who wound up working at the local comic shop, Captain Blue Hen. And that was sort of the way of things until I eventually got my Marvel internship and then my regular job. I don’t know that this is much of an answer so much as a litany of names that don’t mean anything to anybody else—but if nothing else, it was fun to walk through these memories again a little bit.

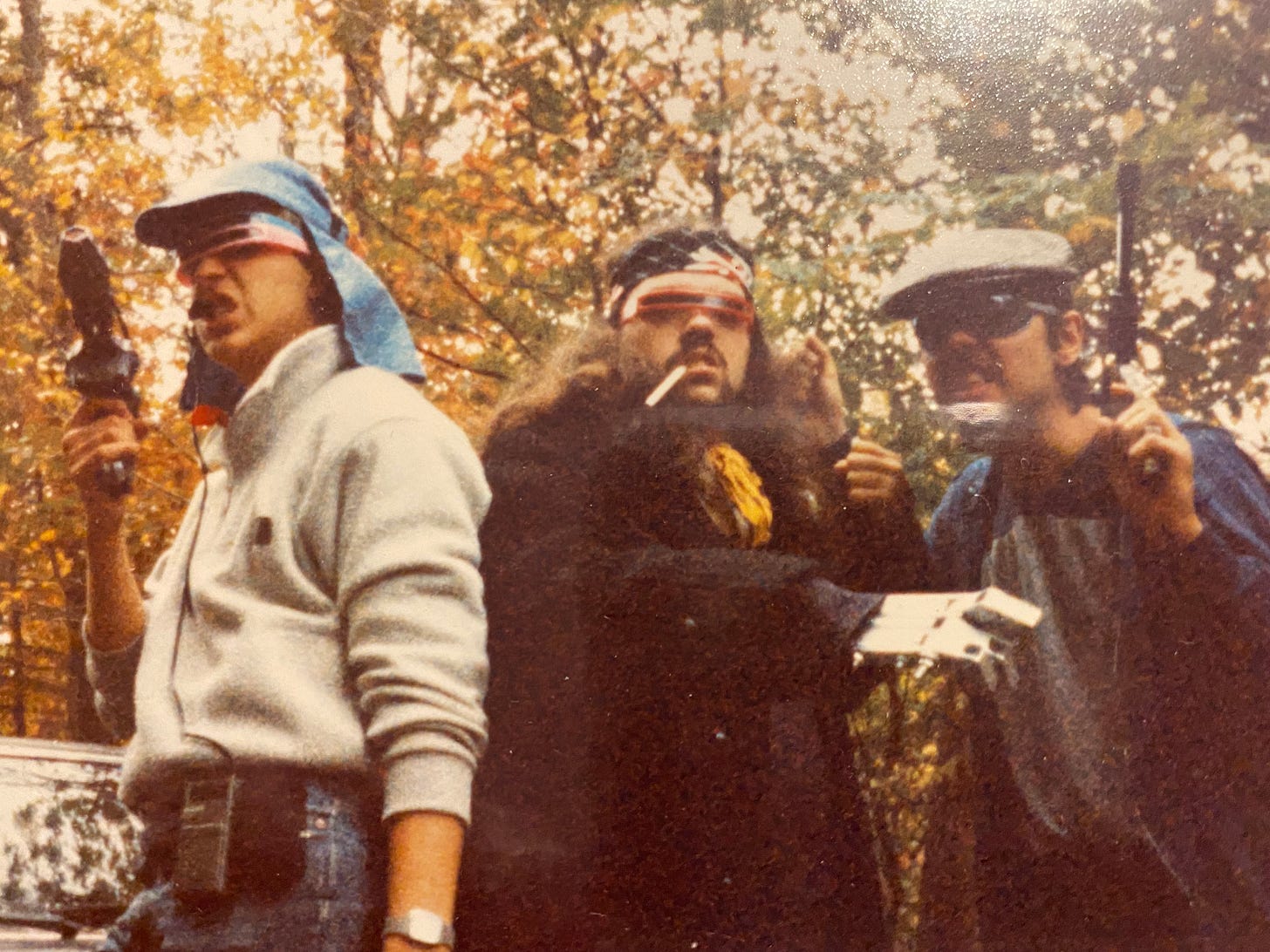

(L-R: Steve Cicala, Frank Strom and I play villains in a never-completed student film shot by Brian Cirulnick)

Behind the Curtain

.I got into a bit of a verbal scuffle with Rob Liefeld online the other day concerning this next piece, so I thought I would share it with everybody.

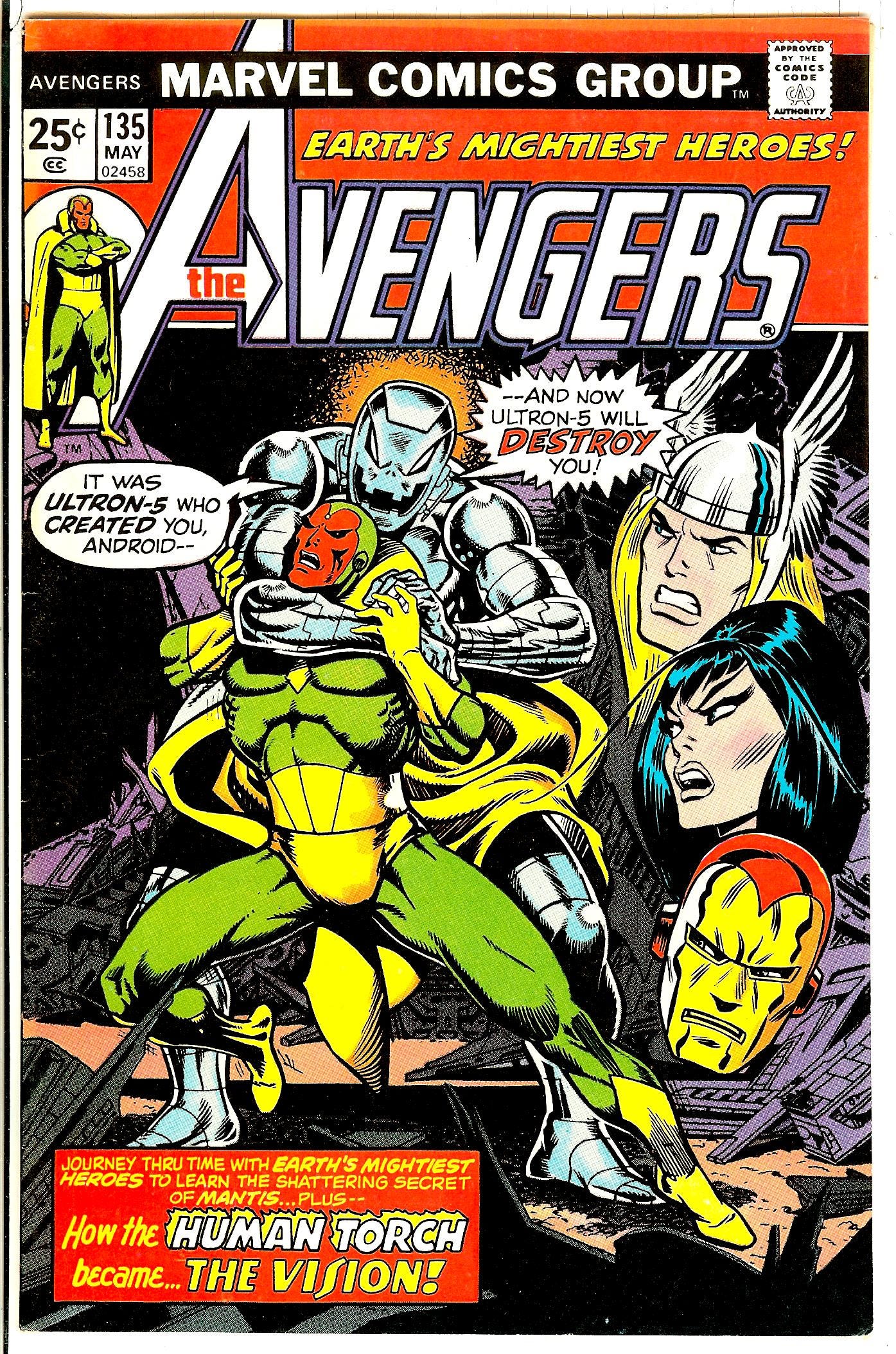

Above you see the cover to AVENGERS #135 as drawn by Jim Starlin. As you can see, even at this stage, some corrections have been done to it. The Vision’s legs in particular appear to have been funked with. Which makes sense—even as they are, they’re a bit too long and distended. But this wasn’t the end to the adjustments made to this piece.

Here’s the cover as it saw print. And you can see the extensive revisions that were done to it. First off, the figure of the Original Human Torch has been removed from the background. That maybe makes sense, as he’s the same character as the Vision and so having them both occupy the same physical space may be confusing. Less understandable is the fact that all three of the inset headshots have been completely redrawn by Marvel art director John Romita. It was this that Rob expressed his displeasure with, having been the victim of similar alterations to some of his early NEW MUTANTS covers. He laid the blame at Romita’s feet, which is why I spoke up. Because the true culpability isn’t so cut-and-dried.

Yes, John executed these changes, as he did on innumerable other covers during his tenure. But he never did so on his own devices. Rather, such changes were asked for by the editor, and John (or an artist working under his supervision as part of the “Romita’s Raiders” training program) would carry out those instructions. So while Rob wasn’t wrong to be unhappy at the changes that were made, both to his own artwork and to others, putting all of the blame on Romita felt to me like overlooking the truly responsible party.

That party certainly changed depending on when the alterations were asked for. But for example, on any title that I edited, if any changes of this nature were made to a cover, it was because I asked for them, and I am the one who ought to be held to account. (For Rob on NEW MUTANTS, the person calling for changes would have been Bob Harras.) And on this piece, while it’s possible that these changes were requested by Stan Lee, who might occasionally comment on a cover going through the Bullpen in the 1970s, the most likely instigator was editor Len Wein. Len had a habit of messing around with the cover images, possibly one instilled into him by Stan (who did much the same sort of thing when he was directly editing the line) But regardless of the reason, the period during which Len served as the primary editor of the color comic book line coincides with the period in which changes of this sort to the cover artwork were the most prevalent. It’s a nice cover either way, but certainly one has to question just how necessary a bunch of those alterations truly were, not to mention how many additional copies of the book they might have sold. I’m guessing not many.

Pimp My Wednesday

We’re keeping busy! And I’m hoping your wallets are fat and bountiful for the Wednesday haul to come!

We previewed it in our inaugural Newsletter months ago, and now the first issue of ALL-OUT AVENGERS is headed to your hot little hands! It’s an all-action jump-right-in-the-pool spectacular that opens mid-story and races to an electrifying climax! The writer is Derek Landy, while the art was produced by Greg Land, Jay Leisten and Frank D’Armata. Try it—you’ll like it! And then the ongoing mystery will have you hooked!

Elsewhere, Kieron Gillen and Guiu Vilanova continue to expand on the Eternals’ viewpoint on the events of AXE JUDGMENT DAY in the second issue of AXE: DEATH TO THE MUTANTS. I’m very pleased with the way the assorted tie-in issues for this Event all worked out, any of them would be worth your time and attention. But in terms of the material most relevant to the spine story being told, it’ll be the issue written by Kieron, which isn’t really much of a surprise.

Here’s another surprising logo treatment originated by Bullpen designer Carlos Lao, one of the things that makes me appreciate his skills so much. Truth is, I never had any intention of running the logo on the window in this manner before Carlos went ahead and set it up this way. But once he had, I couldn’t come up with a better arrangement. I did think that maybe the logo wasn’t quite as legible as it might have been, leading us to add the small words MOON KNIGHT above the Marvel box for any confused prospective readers. Anyway, it’s another masterwork from Jed MacKay and Alessandro Cappuccio in which Moon Knight, now allied with his alters for the first time in our series, begins to hunt down the power behind the mysterious vampire pyramid scheme, The Structure.

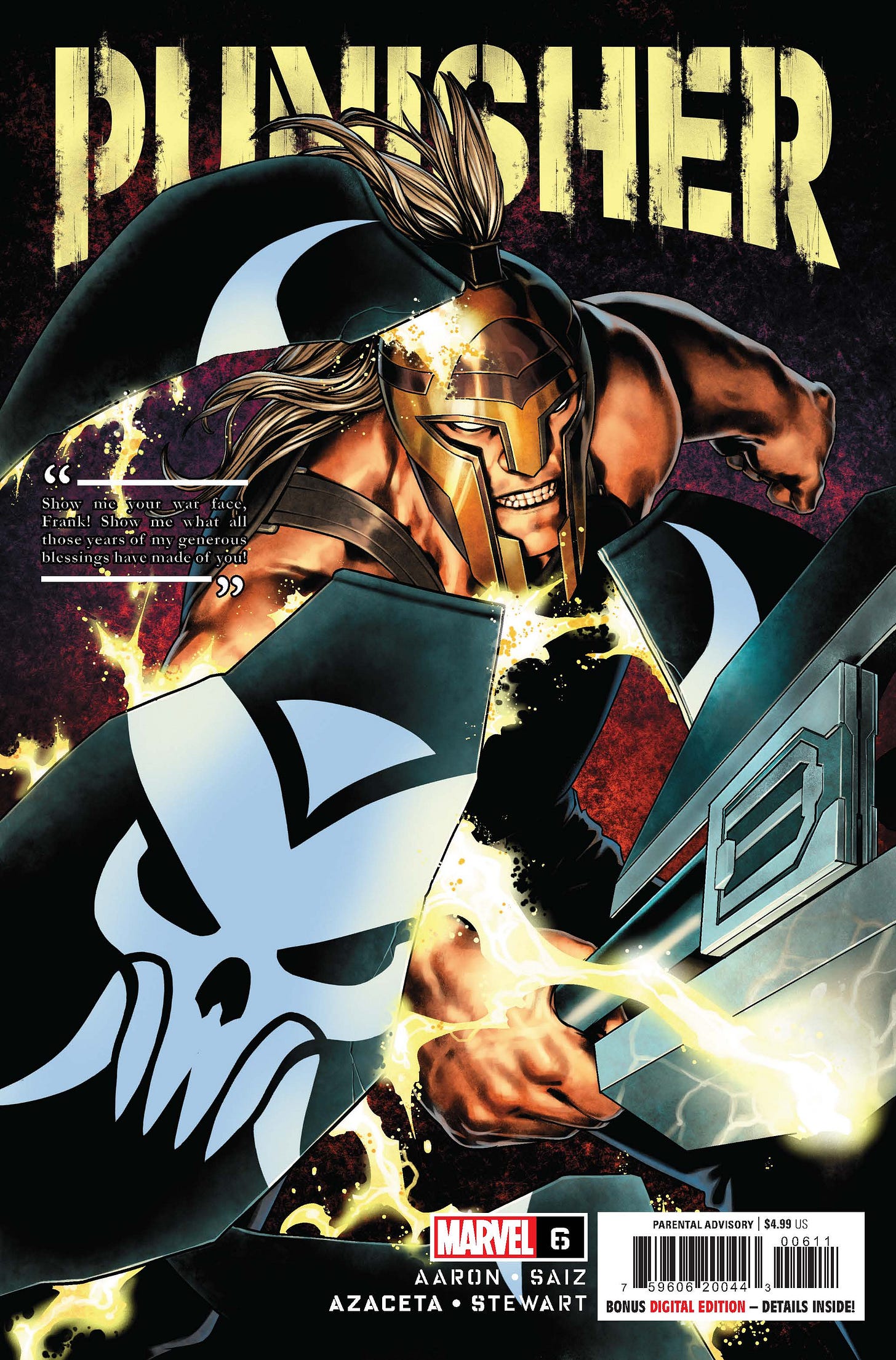

And PUNISHER reaches its midpoint with a brutal showdown between the newly-minted Hand of the Beast and the God of War, Ares. And as always, there are some additional revelations concerning Frank Castle’s past along the way. As with the previous installments, this one is brought to you by the killer creative team of Jason Aaron, Jesus Saiz, Paul Azaceta and Dave Stewart. I do worry that the pull-quote on this cover is too difficult to read, but that was the only space where we thought we could fit it, and the style that we’d already established on prior issues.

Meanwhile, in Las Vegas, Peter David and Alan Robinson continue to unfold an unrevealed adventure of the temporary NEW FANTASTIC FOUR team made up of Spider-Man, Ghost Rider, Wolverine and the Gray Hulk, all under the watchful eye of my assistant editor Martin Biro. This is also about the point where the actual Fantastic Four join the story in a major way, so events grow only more chaotic from this point on—with a familiar demoniac figure pulling the strings. Looking at it now, I wonder if this cover might not have benefitted from a word balloon from one of the reacting heroes. There’s some nice dead space for one above the Hulk.

And in the AVENGERS UNLIMITED track on MARVEL UNLIMITED, Murewa Ayodele and Dotun Akande’s “The Kaiju War” begins to take flight as Iron Man, War Machine and Ironheart are all that stands between a civilized planet and the rampage of a horde of colossal creatures. This is actually issue #11 rather than 009 as depicted on this graphic—don’t be fooled! These vertical Infinity Comics use a different set of storytelling muscles than our typical comics, and I feel like we’re only just beginning to understand all that the format can do. So there are more exciting things coming in the weeks ahead.

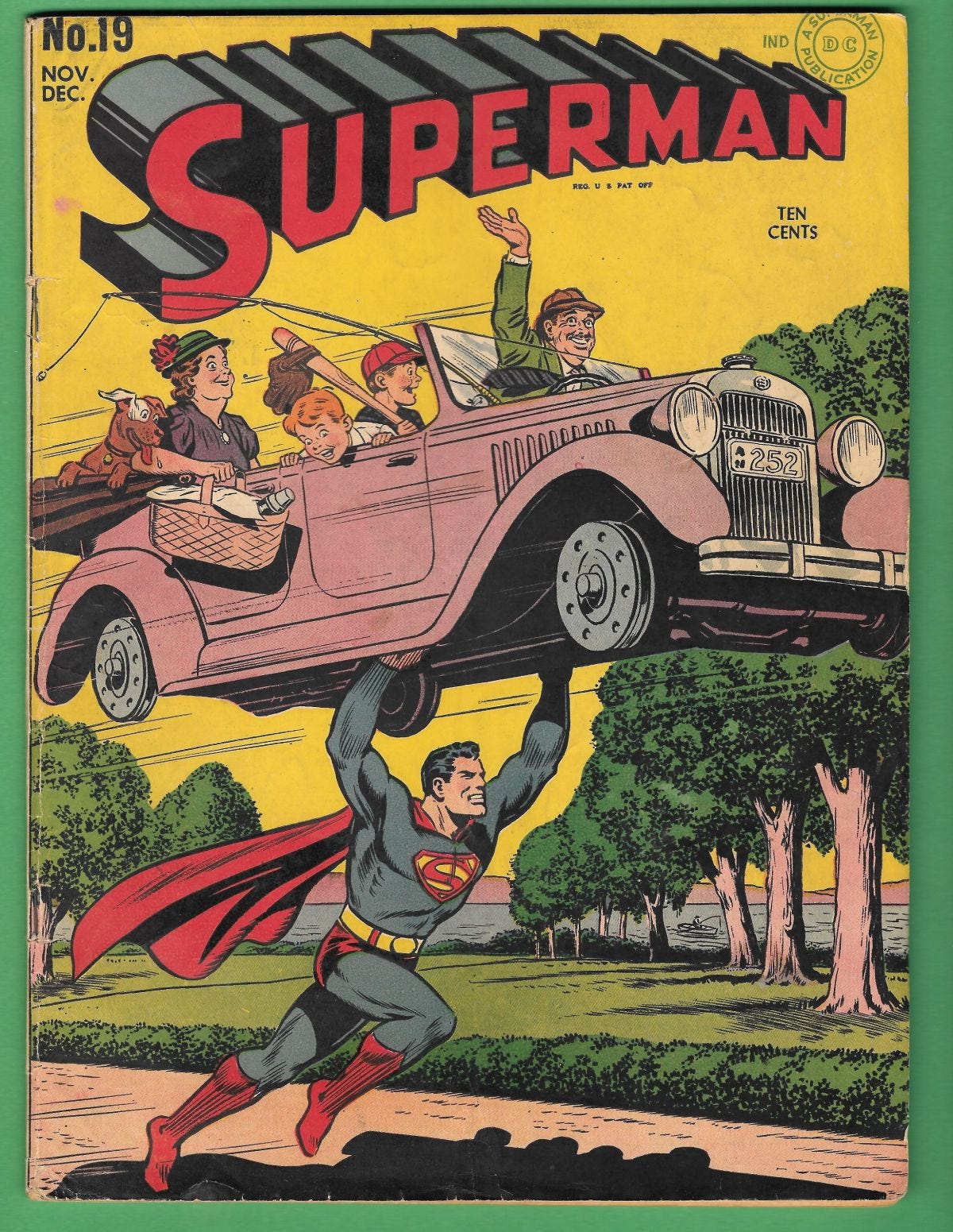

A Comic Book On Sale 80 Years Ago Today, September 4, 1942

This issue of SUPERMAN is worth spotlighting for a couple of reasons. The Man of Steel was still incredibly popular during these years, with his adventures having conquered other mediums beyond just the comics. And two of the four stories in this release showcase that in their own ways. They’ve also been reprinted on more than one occasion. The first, “Case of the Funny Paper Crimes” involves a criminal who’s devised a ray that will animate menaces from the Daily Planet’s comics page, hurling them against the Kryptonian Crusader. The real gag here, though, is that when the villain Funnyface is unmasked, he’s drawn to look exactly like Superman creator Jerry Siegel. His motivation: he was tired of toiling in obscurity, never having hit the big time as a cartoonist like the makers of the strips whose characters he brought to life for his criminal gain. Talk about a thinly-veiled autobiography! (By this point, the SUPERMAN newspaper strip was appearing in over 400 newspapers nationwide on a daily basis, and was likely where most adults knew the character from.) The Man of Tomorrow was also appearing in a national radio show airing three days a week on the Mutual Network, which is advertised in this issue. But Superman’s biggest star-turn up to this point came when he became the subject of a series of animated cartoon shorts produced by the Fleisher Brothers Studios. These cartoon shorts were the most expensive produced up until this time, and are still amazing works of art today. The first of them, which has a relevance to this issue, can be viewed at this link. In an attempt to cross-promote the series of shorts, Jerry Siegel wrote the story “Superman, Matinee Idol”, which also saw print in this issue. It’s set up as a sequel to that first cartoon, but with a twist: the story is itself a cartoon than the real Clark Kent takes Lois Lane to see at a nearby theater. But Clark realizes that he cannot allow Lois to see his animated self change from Kent into Superman or else it will mean the end of his dual identity. (Clark doesn’t appear worried about anybody else in the theater who may see the same thing, but that’s the joke of the story, after all—you need to just go with it.) This adventure has been reprinted a number of times over the years as well, albeit with some unfortunate alterations made to it. I covered those different versions at length in this story from over at my website.

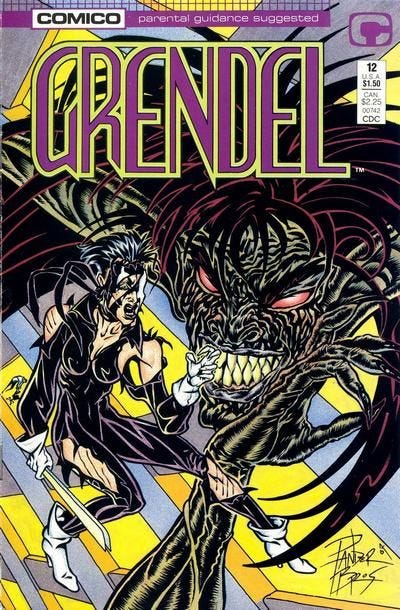

A Comic Book On Sale 35 Years Ago Today, September 4, 1987

GRENDEL #12 marked the end of the first storyline in this series, as well as the revelation that creator Matt Wagner’s ambition for the title was larger than we had initially thought. Wagner had come up with the Grendel concept years earlier as the first strip he would do for the new Philadelphia-based comic book company Comico. It turned on a very basic concept: the lead character was an attractive and accomplished criminal, pursued by a monstrous and savage hero, a reversal of the typical tropes where beauty equaled virtue. The series lasted for three issues before Wagner stopped pursuing it in favor of his color title, MAGE. But it was an idea he couldn’t completely put in his rear view mirror. He wound up reworking his ideas for the Grendel storyline into a more art deco-influenced style and ran it as a back-up in MAGE, “Devil By The Deed”, where it developed a following. The story ended with the death of his lead character, Hunter Rose, but by that point Wagner had come up with his true thesis for what the GRENDEL series would be about. So in this initial storyline, journalist Christine Spar, who had written an investigative biography concerning Hunter Rose (her volume was said to have been “Devil By The Deed”) Spar herself ends up adopting the Grendel identity for her own personal mission of revenge, one that ultimately consumes her life. At the outset, this appeared to be a simple legacy character switch, where Spar would be the new regular title character. But Wagner was more ambitious in his storytelling. In his new conception of the character, Grendel was something more akin to a possessing entity, which would pass from person to person over the course of hundreds of years of storytelling. But all of that was still to come at this point—though the unexpected demise of Spar in this issue certainly signaled that something different was on the horizon. (In the next storyline, Spar’s boyfriend Brian Li Sung defies possession by the spirit of Grendel, sending it into a forced hibernation for generations). The stylized and classy artwork on the Christine Spar storyline was handled not by Wagner himself (who had drawn the Hunter Rose material), but rather by Jacob and Arnold Pander, who gave the series a distinctive look unlike anything else on the racks. In the era when Frank Miller-style noir crime super hero stories were all the rage, GRENDEL fit right into the gestalt, while simultaneously constantly pushing the boundaries in interesting ways-=-graphically, in terms of subject matter, and in the scale of its long-term world-building. It was a very smart series in all of its iterations, but has sadly been forgotten by most over the years. If anything, it was something of a precursor to the sorts of DC Universe-adjacent titles that Vertigo would eventually umbrella. I’m told that Omnibuses collecting the entire run are coming into print shortly, to coincide with a GRENDEL television series, and they’ll be well worth readers seeking out. The book operated just a hair outside the spotlight, but for those who encountered it back in the day, it became a special favorite.

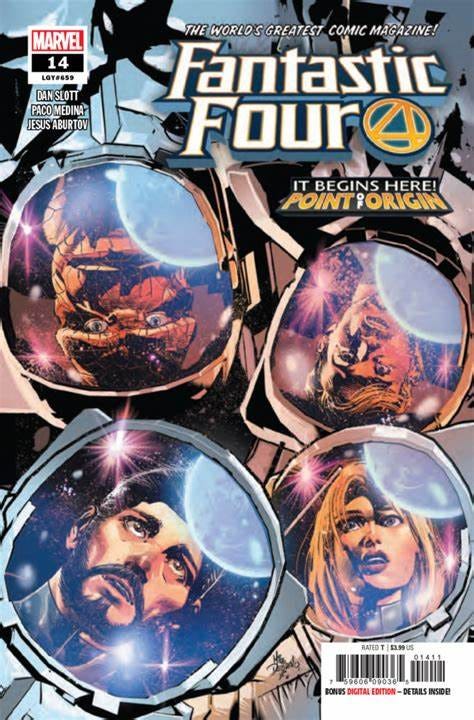

A Comic I Worked On That Came Out On This Date

A more recent book than we’ve showcased up until now, but what the hell. Dan Slott’s tenure as the writer of FANTASTIC FOUR has come to a close, and so now we can look back over the whole of it and evaluate it as a singular body of work. In doing so, it’s clear to me that, while the run had its typical ups and downs along the way, its highest sustained point comprised issues #12-14, of which this one was the last. After a rushed start and some difficulty in maintaining a regular artistic team, things had begun to settle down and get back on track. But then, the Pandemic hit, making everything a bit more difficult to deal with. Still, #12-13, with its Thing vs the Immortal Hulk battle, was terrific and expertly paced, a terrific twist on the classic Thing vs Hulk conflict and a story that allowed Ben Grimm to chalk up his first no kidding victory over his green-skinned foe. And this next issue, and the storyline it kicked off, “Point Of Origin”, turned on the sort of clever character concept that Slott excelled at finding. Given the passage of time, the group’s origin had been updated from having been an attempt to reach the moon to a test of an intergalactic star-drive. But the question that had never been answered up until this point was: where was it they were trying to go? From that simple idea, Dan and guest artist Paco Medina crafted an issue that owed much to the Apple TV drama FOR ALL MANKIND, in which the Fantastic Four are guests at a Smithsonian exhibit dedicated to their first flight (and in which we meet the two astronauts who were supposed to be a part of that voyage, and who missed out when Reed hijacked the rocket along with his fiancée and her brother.) Thereafter, Reed is inspired to attempt to duplicate and complete the team’s original mission as it would have gone had they not been caught in the cosmic storm that gave them their powered and knocked them back to Earth. Along the way, we get to experience flashbacks to those halcyon days, and in particular the journey of Johnny Storm, who feels compelled to be a part of the mission and who is able to keep up with every bit of prohibitive training flight leader Ben Grimm is able to throw his way. It’s not an action story by any means, it’s more about the spirit of adventure and exploration that forms the crux of the Fantastic Four’s identity. Unfortunately, the remainder of the “Point Of Origin” storyline stumbled a little bit, both because Slott was simultaneously working on IRON MAN 2020 and was thus stretched, and because we ran into further artist problems which wound up splitting up several issues among multiple pencilers. So the whole story had more good story ideas than could readily be serviced in the space we had, and an inconsistency of artwork that helped to keep the new characters, the Unparalleled and the other inhabitants of the Planet Spyre, from gelling into complete characters. We were trying to introduce a new group of players into the Fantastic Four’s world along the lines of the introduction of the Inhumans back in 1965, but the characters never quite came together enough to pop off the page in the way that would have demanded. Sometimes things work out that way. But this issue as a single issue is still very strong in my eyes. It was print only three years ago, on September 4, 2019. A very nice Mike Deodato cover on it, as well.

Monofocus

again this week, not too much new to report on the watching/reading front beyond the shows I’ve already spoken about. I finished NEVER HAVE I EVER’s new season, have one episode to go on MOVE TO HEAVEN, which wound up being a very different series than what I was expecting, and am deep in LIAR GAME 2, the sequel to the first series. I did enjoy the extra SANDMAN episode drop, which came just as I was wrapping up that series, and which was among the strongest entries in the run. And it seems likely at this point that I’ve given up on PAPER GIRLS three episodes in, as I haven’t been back to it in some weeks.

I did take in an episode of the documentary series CULTURESHOCK on Hulu the other night, one dedicated to the making of Judd Apatow’s short-lived television series FREAKS AND GEEKS. I hadn’t watched FREAKS AND GEEKS when it first aired, apart from one random episode that I caught—the network scheduled it poorly, which is one of the reasons it wasn’t able to get much traction—but I caught the whole thing a few years later when it reran on Fox Family. But at that point, I was all in on it, and was there when its quasi-sequel UNDECLARED ran for its similarly underperforming year on Fox. The episode itself was pretty great, a nostalgic look back at a series that I haven’t revisited in many years, but whose emotional moments really stuck with me. That series had a ton of talent involved with it, faces that you instantly recognize today but who were just a bunch of people when it first aired in 1999. And I learned something new that applies to our world, a fact that floored me just a little bit: John Francis Daley, the actor and performer who played the lead geek Sam Weir in the series went on to become one of the writers of the SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING film. Small world!

I also thought that this week’s second episode of the new season of STAR TREK LOWER DECKS was a return to form, after an initial episode that felt like homework, like the writing staff having written themselves into a cliffhanger that they weren’t really all that interested in resolving. But this week, it was back to missions and interpersonal drama and deep cut STAR TREK fan service, and it was pretty great.

That’ll take care of things for another week, it seems. But we’ll all meet back here in seven days’ time for more obscure references, half-baked answers and absurd media observations. In the meantime, keep chasing those dragons!

Tom B

Wuau, a big one this week! Once again, thanks for answering my question.

Regarding the "What’s the best “last issue” of someone leaving a significant Marvel run?" topic: Dan Slott on Amazing Spider-Man. He could had gone out with #800 and already be absolutely fantastic. But then along comes #801 with Marcos Martin and they delivered one of the best single issues in the entire Spider-Man history. It's absurd how good that issue is, I simply love it.

Another recent one: Immortal Hulk #50. I loved the entire run and the last entry felt like an all-encompassing, all-out take on its themes and purposes. A beautiful issue that, emotionally, felt compassionate and hopeful. "Hulks should forgive Hulks. Someone has to". The fact that the creative team lasted all the 50 issues (regardless of what I nowadays think about the artist) makes it even better, closing a complete package and a true modern-classic.

I have to mention another one. Spider-Man #240, Bendis' last issue with Miles - and the end of what was originally the Ultimate Spider-Man book as we knew it. I know a lot of people probably won't agree with me, but I do think it deserves to be recognized as one of the best made by the guy during his run. That last page says it all. I basically grew up in comics with this series. Ultimate Spider-Man and Bendis work is always close to my heart. So, yeah, amazing last issue of a legendary run.

Thanks so much, Tom, that was exactly the kind of answer I was hoping you’d have and I’m gonna cherish it. I have a few follow-ups, but I’ll stitch them in during work calls. :)

And I do hope one day I am remembered for having conversations with people who felt like they “don’t know that this was useful, so much as a litany of stuff that doesn’t mean anything to anybody else — but if nothing else, it was fun talking to Rickey.” :)