Yeah, it’s happened again. Another of the great masters of the comic book field have left us. This is turning into a brutal year for the fortunes of artists.

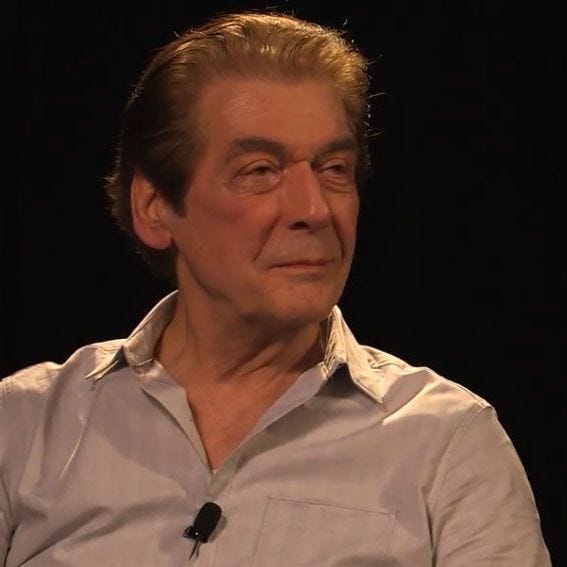

Tom Palmer is best known among the comics cognoscenti as an inker, but he was much more than that. He was a fully-rounded artist, who did as many commercial jobs as he worked on comic book stories, delivering on them with a quiet professionalism and gentle humor that made many of us refer to him by the sobriquet The Last Gentleman In Comics. Not only was Tom a thorough professional with an abiding love of the field and of the world of illustration in general (The Society of Illustrators was a favorite lunchtime spot of Tom’s in the years before it became open to non-members, and he would frequently take guests to lunch there) but he was a decent person as well, with a strong set of values that guided his life and his behavior in a sometimes-tumultuous field. He was also a field teacher, passing on what he knew about color theory or compositional know-how to an entire generation of younger artists and editors, often unprompted. And always with a gentle manner. It’s not that Tom didn’t get mad, he simply never let any anger he may have been experiencing control his actions. He had grown up as a “neighborhood kid” and he always remembered the code of the neighborhood, even after he’d left it behind. Most freelancers who would come up to the big companies, Marvel and DC, to drop off work expected to be taken out to lunch, to be wined and dined a little bit. Not only was that not Palmer’s outlook, but he took the opposite approach. He would routinely invite groups of editors and artists out to dinner at one of the many restaurants he regularly frequented. (The staff almost always knew him on sight.) Those lunches were luxurious, with a code that mandated that everything said at the table remained at the table. And they were long—they went on for three, three-and-a-half hours, during which time the editors especially were expected to be on-site and working. Tom insisted on covering the tab for all of them. Every once in a while, we would find some way to outmaneuver him and pick up the check, but not often, and never the same way twice. Tom was also very humble, with a good word to say for all of his frequent collaborators: Neal Adams, Gene Colan, John Buscema, John Byrne, Ron Garney, John Romita Jr.—the list goes on and on. He tended to shun the spotlight himself—it was only in the last couple of years that he started attending conventions regularly and directly meeting his many fans, and that he opened up to doing the occasional interview for publication. One of the best, covering the scope of his life and career, was this one, conducted by Alex Grand and Jim Thompson of the Comic Book Historians site. Tom seemed like he belonged to the Rat Pack generation, with an effortless cool that radiated from him. He is one of the very few inkers in the industry who were able to command a fan following for just how well he embellished and finished the work of a bevy of creators. Gene Colan in particular, whose subtle shaded work was notoriously difficult to interpret in black and white, had no finer creative partner. Tom was a painter as well, but he used that skill more often in his commercial art assignments (and to gift those closest to him with paintings on a notable birthday or occasion.) He was also one of the best colorists in the field, at a time when that discipline was largely considered busy work—in his early days, he would spend a considerable amount of time hand-painting the color guides for the stories he was inking, turning them into little finished paintings that the separators could still understand and replicate on the printed page. I’m pretty sure that the last time I was Tom was at the 2019 Baltimore Comic-Con (or, honestly, it could have been the 2018 Baltimore show—time has become very fluid in these past few years) where we was set up at a table with his son, editor Tom Palmer Jr. of Wizard magazine and later DC Comics. And I’m not sure when the last time I worked with him was—it may have been as far back as that issue of NEW AVENGERS, #16.1, that Neal Adams penciled, which would have come out a decade ago now. Hard to believe—just as it’s hard to believe that the check has come on that final Palmer lunch, the bill has been settled, and it’s time for everybody to go home (or back to work.)

I had one or two other topics that I intended to talk about in this space, but following on from that Tom Palmer write-up, the moment doesn’t seem correct for them. So we’ll save those topics for another time, and instead turn to a few more questions that you guys lobbed my way

Jason Holtzman asks:

Entering in the realm of questions, and I believe you’ve touched on it before, do you ever concern yourself with the notion that newer generations could be too “cynical” for superheroes? It has been noted by writers that hope can be harder to pull off and get people to buy into.

For me the most illustrative example would be Batman and Joker’s conflict. Sadly due to recent events some of the Joker’s actions can no longer be seen has highly imaginative escapsim-ish type danger but instead are events that too regularly occur with lasting real life consequence. This, coupled with Joker’s tendency (in my opinion) to be presented not so much as insane but just plain evil, makes it hard to feel as though Batman saves the day when he sends the Joker to be broken out of Arkham again. Some days Batman’s taking of the high road seems harder and harder to digest. While I’m not advocating for Batman to execute Joker or anything, part of my wonders if the cylindrical nature of Batman and Joker will grow old to readers as outside pressures crack some of the escapism of stories.

I think this is a complex question, Jason, and one that every individual reader and creator is going to need to work out an answer for themselves. But here’s mine. I’ve written a bit about the difference between the manner in which heroism is depicted in cinema and in comics, and why that is—if you missed that Bonus Newsletter a few weeks ago, you can find that text here. But speaking more plainly to your question, I don’t think that the audience as a whole is too cynical to accept heroism—if anything, I think people are hungry for it, especially in a world where so many of our depended-upon institutions have failed us. Cynicism tends to be an adolescent outlook, one that gets adopted as kids grow older and learn more about the reality of the world. And certainly, that cynicism can stay with some people their whole lives. But others are looking for some inspiration, some hope, whether they realize it or not. Getting into your Batman example, I think what you’ve presented here and what gets presented elsewhere is a skewed version of the question. You see, I don’t think that Batman, or any similar super hero, is in the right solely because he’s the strongest person in the story. Sure, that physical vitality and power wish-fulfillment is a great portion of the appeal of super hero stories (and heroic fiction in general.) A Batman who is right because he can beat everybody up sounds to me like the rhetoric of the Zack Snyder crowd, who simultaneously want to be seen as in pursuit of greater realism and who want their sense of nihilism justified. At any given moment, the stories we tell ourselves reflect what we’re feeling about the world, and it’s difficult to remain hopeful given all that has been going on for the past decade. No, to me, what makes Batman heroic is that he has a code of conduct by which he lives, one that we can understand and believe in, even when it seems hard, even when it’s something that we would not be able to abide by ourselves. I don’t believe that Batman has the right to kill the Joker—if you subscribe to any version of any doctrine that espouses Thou Shalt Not Kill as one of its tenets, then that’s an absolute. And I don’t believe that Batman is responsible for the future actions of the Joker—that is the perspective of a vengeance-seeker attempting to justify their desire for fatal action. It’s a paper tiger argument fueled by the thirst for an eye-for-an-eye retribution, the catharsis of wanting to see the bad guy get his in a manner that is proportionate to his offenses. It’s a staple of popular cinema, as we talked about in that earlier piece. And yes, Batman turns the Joker over to the authorities, and places him into the arms of a flawed system that inevitably ses him released back into the world to maraud again—but the reality is that this happens because this is all fiction, because we want to see Batman contend with his ultimate nemesis, and that it’s a conflict that audiences haven’t grown tired of for 80 years. In a society, there are laws by which all members agree to abide. In the fictional world of Gotham City, it falls to the proper duly-elected officials and justice system to determine the proper punishment for the Joker’s crimes. Sure, Batman could kill the Joker—he’s certainly acting outside of the law in the first place to carry out his vigilante war against criminals. But doing so would violate his own personal code, the code that defines him as a hero. At that point, the difference between him and the Joker isn’t so great—each one unleashes fatal violence to satisfy their own urges, regardless of what others may think or feel about it. The only difference is that Batman has his name on the cover, so he must be the good guy. I try to hold my heroes to a higher standard than that. And it’s not as simplas just killing or not killing. In theory, Wolverine has a personal code that has no compunction when it comes to killing if the circumstances warrant it. But there are good Wolverine stories and poor Wolverine stories, and the difference usually tends to come down to which ones are simply exercises in violence for the sake of catharsis alone, and which ones have the character struggle with keeping to his own code of behavior. The fact that Wolverine is willing to kill, and is sometimes eager to kill, doesn’t make him a hero. It’s the fact that there are certain conditions that must be met in order for Wolverine to unleash his murderous side, and that it’s something that he struggles with. The struggle is the heroic part, not the violence.

One more hopefully simpler question, from a reader who signed himself only as JV:

I had a question in regards to a quote from your blog - how you state (paraphrasing) that "Thor can be in Asgard but needs to come to Earth once in a while to fight the Absorbing man".

Do you take that into account as an editor when a new writer comes onboard? In regards to the general direction of a series? After the Multiversal antics of the Aaron Avengers do you want the next writer to give us the 5th ave mansion and the team fighting the Masters of Evil? or is it solely based on the best pitch?

Every series is different, JV, and so when it comes time to bring in a new creative team on a title, I’ll definitely sit down and think about what the book has been doing well, and what it hasn’t been doing so much of. What the audience seems to be reacting well to, and what aspects of the series are being overlooked. With Jason’s AVENGERS run still ongoing, I’m not really going to be comfortable talking publicly about what I might be looking for out of the next guy. But I will have some thoughts to share, a basic trajectory to impart. But at the end of the day, as you say, the best pitch wins. Over on HULK, when we brought the character back in AVENGERS: NO SURRENDER and were poised to spin off a new series—which became IMMORTAL HULK—I had some definite thoughts on how that should all go. And I wrote up those ideas (and even a sample scene) and gave them to everybody who was wanting to pitch for the new title. I believe we even reprinted my synopsis in one of the first IMMORTAL HULK hardcovers if you want to take a look at it. In the end, Al Ewing got the assignment—and what he did with the series right from the start wasn’t exactly what I had described in my precis. Which was fine—more than fine when a title performs as strongly as that series did. But you can look at it and get a sense of connection between the approach as I laid it out and what Al eventually delivered. By the same token, that series and its stories were far more his than mine. I simply provided a signpost along the way. So that’s how you do it, at least if you are me.

Behind the Curtain

I’ve realized that pretty much everything that I’ve shown in this space so far has been Marvel-related. Which makes sense, given who and what I am. So this time I dug around through my files to find a cool bit of something related to DC, just to switch things up a bit.

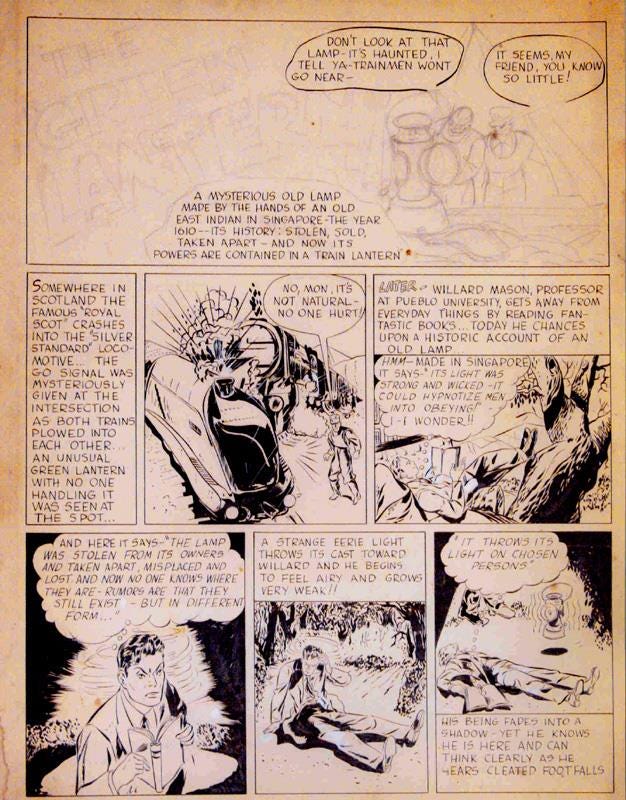

What you see here is the incomplete first page to the first Green Lantern story—not the one that eventually saw print, but the one that artist Mart Nodell whipped up in order to attempt to sell the character. You see, at the time, Nodell was working freelance in the comic book industry but didn’t really have a steady account of his own. A visit to the offices of All-American Comics (the unofficial sister operation to DC/National Comics) led him to learn from editor Sheldon Mayer that their namesake title, ALL-AMERICAN COMICS, was looking for a new lead feature. Specifically, Mayer probably said, “a Superman” as that was what everybody who was anybody was knocking off in comics at the time. So if Nodell could come up with a fresh character in that mold, he could have an important regular feature. As legend has it, on his way home that day, passing through Pennsylvania Station, Nodell happened to see a linesman first raise a red lantern in order to prevent a train from starting out from the station due to some unsafe condition, and moments later a green lantern when it was safe for the train to head out. The image stuck in his head—the Green Hornet was then a very popular character on the radio, so green already had an association with super-heroism of a sort. Springboarding off of that idea, Nodell came up with the idea of a character who would be a modern day Aladdin—except that his magic lamp would be a green railroad lantern. He wrote and drew up the first three or four pages of an initial story and brought them in to editor Mayer—who promptly rejected them. He didn’t like the writing and thought the whole idea was half-baked. But there was something about the underlying concept of Nodell’s concept that appealed to him. So he suggested that Nodell work on developing the strip with writer Gardner Fox, who had previously originated the Flash and Hawkman for the firm (and who had also written a few of the earliest Batman stories.) This proved to be a good instinct, as Fox refined the concept. Rather than walking around carrying the unwieldy lantern all the time, Fox suggested that the character should instead forge a ring out of some of the lantern’s material—a ring that would give him his fantastic powers, but whose potency had to be reset every 24 hours by making contact with the source lantern. Fox also changed the main character’s civilian name from Willard Mason to Alan Scott—he had intended to use the name Alan Ladd, as a reference to Green Lantern being a modern day Aladdin, but Meyer thought the name sounded ridiculous and unbelievable. Only a year or so after Green Lantern debuted, Alan Ladd became one of the biggest movie stars in the nation, and even had his own DC comic. Oops. Today, Green Lantern is one of the pillars of the DC Universe, though in a very different form than what is presented here. But that whole journey began with this seldom-seen page.

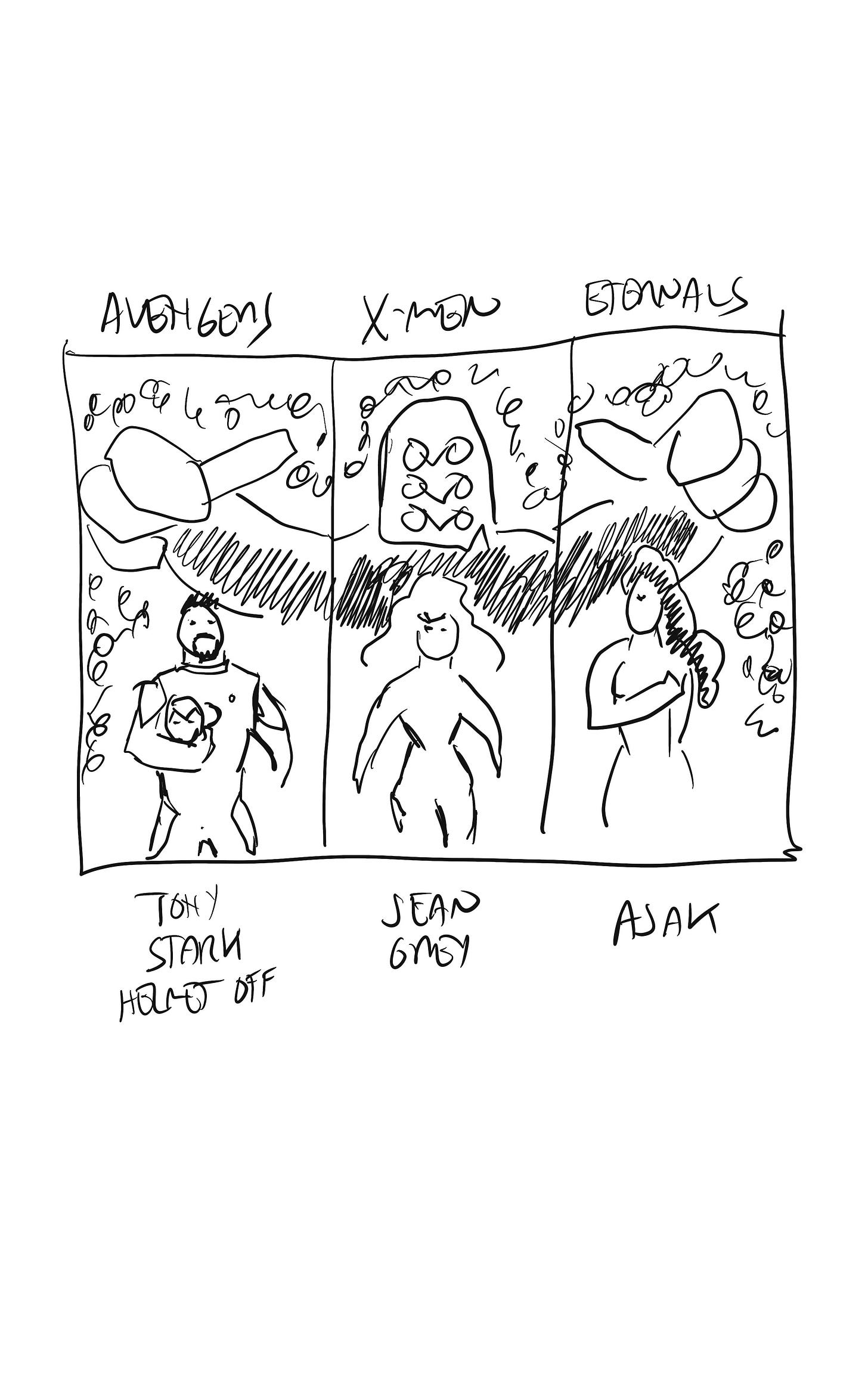

And for those who can’t sleep at night unless they receive sufficient Marvel content, here’s another example of a crappy little cover sketch that I did to get the idea of a set of covers across to an artist. This sketch is for the connecting covers to AXE AVENGERS #1, AXE X-MEN #1 and AXE ETERNALS #1, the three one-shots that carry forward the AXE: JUDGMENT DAY storyline between issues #5 and #6. I did this to give the eventual artist Nic Klein a sense of how I saw the three covers being divided up.

And here is the final image by Nic for those three covers. As you can see, the finished piece is exactly like my sketch yet also completely different in any number of key ways. The color on this is really nice, popping the three spotlighted characters well by keeping the background and the environment largely monochrome. Nic could have done the whole job entirely on his own—but giving him this crude sketch let him know what I was thinking in order to give him a good starting point, much as I talked about in the question about new oncoming writers above.

Pimp My Wednesday

What new excitement and surprises await you at your local comic shop this Wednesday? Let’s find out!

AVENGERS FOREVER #8 continues the Pillars story arc and focuses on a very different, very unique version of Thor, who in this universe is no longer the God of Thunder. Just what he is and what he becomes you’ll have to discover for yourself. It has to be said that artist Aaron Kuder is really going to town on these Pillars issues—this one is all kinds of great in its storytelling choices. Some very fine color work from Lee Duhig and his GURU-eFX studio, too. Of course, it’s written by Jason Aaron, who is truly giving his imagination a workout on these stories in a way that I hope readers appreciate.

And AXE: JUDGMENT DAY #3 takes us to the almost-middle of that series—I say almost because there are three critical one-shots that come out in-between AXE JUDGMENT DAY #5 and #6 that are legitimate parts of the story, so the whole thing is actually nine issues in length, rather than six. You can blame the big eyes of writer Kieron Gillen, who was lamenting just this week that the entire project began with him only writing five issues—he’ll have authored something in the neighborhood of three times that by the time the Event is finished. Also, now that issue #2 has dropped, it’s become a bit more apparent what this story is actually about, and the larger questions and issues it was designed to address. It’s terrific fodder for the kinds of heroic discussions that we had above, and you’ll see these questions reflected in a number of tie-in issues across the Marvel line in the weeks to come. Can’t forget to mention that effervescent artwork of new father Valerio Schiti, who has been working his tail off in and around the blessed event. Will it kill him? We’ll all know the answer by the time the final issue comes out!

Elsewhere, it’s time to say goodbye to writer Dan Slott, who finishes up his four-year tenure on the World’s Greatest Comic Magazine with a self-contained single issue story, beautifully realized by artist Cafu. Some will be happy to see Dan leave, while others will be awaiting his return to the world of SPIDER-MAN with baited breath. Either way, there’s one final FF story of Dan’s to experience before we bid him adieu.

Man, this series has been in the works for a long while! I think I started it in early 2019, not long after we put out MARVEL COMICS #1000 in which television writer Adam F. Goldberg wrote a one-page DAMAGE CONTROL story. Adam had been attempting to pitch a DAMAGE CONTROL television series for several years with little success—so when we approached him with the notion of turning his ideas into a comic series first, he was quickly on board, also roping in his frequent writing partner Hans Rodinoff. Because of Adam’s television schedule, we approached the entire project as a slow-burn series, where we’d build up a stockpile of material before soliciting and releasing it. And then, the pandemic happened, and the entire timeline shifted, as well as conditions in the marketplace. We never stopped working on DAMAGE CONTROL (though artist Will Robson did wind up dropping out after the second issue to pursue other opportunities) but we were never certain when we’d be able to get it added to the schedule. But that time is now! And as a special bonus, we also added a back-up story written by Charlotte Fullerton, an accomplished animation writer who was also the spouse of DAMAGE CONTROL originator the late Dwayne McDuffie. It just felt right, you know? That story is drawn by the terrific Jay Fosgitt and will run in this premiere issue. If you know nothing about DAMAGE CONTROL, don’t worry, this first issue is a good primer on what to expect. But if you’re a fan of the original three DAMAGE CONTROL limited series, this is going to feel like coming home for you.

And over on MARVEL UNLIMITED a new storyline is about to kick off in the AVENGERS track. (Ignore that 007 in the lower right corner, it’s actually release #9—I flipped the order of the stories for a variety of reasons, but this thumbnail comes from before that switch was made.) It’s a multipart space adventure called The Kaiju War written by Murewa Ayodele and illustrated by Dotun Akande (whose work on MOON KNIGHT BLACK, WHITE & BLOOD I spotlighted last week) The story puts the spotlight on the “Iron Trio” of Iron Man, War Machine and Ironheart as they face down a planet that has been overrun with Kaiju-sized creatures. Murewa and Dotun first broke into the industry through their work on vertical web comics, so it’s a format they are intimately familiar with, and so the end product is very cinematic and stylish. So check it out, and enjoy!

A Comic Book On Sale 80 Years Ago Today, August 21, 1942

Among the fan community of the early Silver Age of Comics, there was one comic book title of the far-off Golden Age that carried with it a mystique like no other. That title was ALL-STAR COMICS, the home to the most successful (and practically only) super hero team of the 1940s, the Justice Society of America. Created as a novelty, a way to link the adventures of the solo heroes who were being spotlighted by DC/NATIONAL COMICS and sister organization ALL-AMERICAN COMICS from their assorted anthology titles, the Justice Society was profoundly exciting and influential to the readers who encountered it early on. Dr. Jerry Bails, largely credited as the grandfather of super hero fandom, was driven in his endeavors by a love of the JSA and a desire to complete his collection of their adventures—and later, to see them revived. In his travels, not only did he become acquainted with ALL-STAR’s last editor, Julie Schwartz, who was still on staff with DC, but also writer Gardner Fox who had written all of the early Justice Society stories, and who sold Bails his personal bound copies of those hard-to-find comics. One step behind Bails was Roy Thomas, another JSA fan looking to fill out his own collection who became Jerry’s right-hand man in their efforts to bring out the first fanzine dedicated to costumed heroes, ALTER EGO. Roy, of course, went on to have a storied career in the field at both Marvel and DC, and got to write numerous stories featuring the JSA and other heroes of his youth. In recent years, he’s revived ALTER EGO as an informational magazine, and has put out over 150 issues dedicated to scholarship of the history of the field. Anyway, point being, ALL-STAR COMICS had a certain mystique surrounding it within the nascent fandom of the early 1960s. Among those who also loved it was Jim Harmon, an author and expert in the Golden Age of Radio who published an installment of the nostalgia series All In Color For A Dime in the fanzine XERO dedicated to ALL-STAR and the Justice Society. These essays were later collected into a book in 1970s, one of the first tomes dedicated to capturing the history of the early days of comics. In his article, Harmon points to two Justice Society adventures as standing head-and-shoulders above the others. This story, in ALL-STAR COMICS #13, was one of them. In it, the members of the Justice Society (rechristened as the Justice Battalion as part of the war effort) were overcome by Nazi saboteurs using gas and were rocketed to their apparent doom in a series of missile strikes that landed them on other planets within the solar system, each of which sported its own civilization. But the Justice men were up to the challenge, and not only survive the challenges presented by each planet, but to return to Earth with a new weapon to use in the struggle against the Third Reich. In terms of the kinds of stories you’d find in the comic books of 1942 (most of which were, at most, 13 pages in length) “Shanghaied Into Space” was an epic—and like all of the Justice Society stories, it filled the magazine (although the individual chapters featuring the Society members solo still presented like different features—that was still seem as a necessary appeal for the comics.) It’s also noteworthy for being the one and only time that Wonder Woman was given a full chapter in a Justice Society storyline. She had been introduced a few issues earlier and was already overwhelmingly popular—so much so that she was being given a series of her own. By the Society’s bylaws, that meant that she was precluded from taking part in the Justice Society’s adventures. (Membership in the Justice Society was seen as promotional—earlier, both the Flash and Green Lantern had to step down from their Society duties when they had been granted their own titles.) But ALL-AMERICAN COMICS editor Sheldon Mayer didn’t want to lose the sales draw of the popular character, and so she was made the Society’s secretary, who would appear in the framing sequences but take no direct part in the action. Except for this issue. It was a rare chapter where the script was originally written by Gardner Fox but almost entirely rewritten by Wonder Woman’s creator William Marston before it was drawn. It was still a huge novelty in those days to see the stars of two different comic books appearing in the same story together, and that’s what made the Justice Society so intriguing to readers. in later years, shrinking page counts would change up the format, and the JSA heroes would work in pairs or trios rather than alone. But that was all to come in the postwar period. This self-contained epic would have set you back only one thin dime when it hit the racks on August 21, 1942.

A Comic I Worked On That Came Out On This Date

As this is the week that the new DAMAGE CONTROL series is coming out, it felt right to focus on this particular release from August 21, 1990. This was the final issue of the original four-issue squarebound DEATHLOK limited series, on which I worked as an assistant editor under Bob Budiansky. Eventually, a year later, I would wind up the full editor of the ongoing series that spun out of this project—my first as editor. How I drove that book into the ground is probably a story worth relating at some point. But here, things weren’t in such great shape on this climactic issue of the limited series as well. It seemed like we couldn’t win for losing on this project, in part because different people had different visions for the character. To start with, DEATHLOK was being co-written by the late Dwayne McDuffie and Gregory Wright, who was also contributing the color work on this blueline series. While they started out conceptualizing the new modern Deathlok on the same page, as they wrote more and more, their perspectives on the character began to diverge. This wouldn’t have been an insurmountable difficulty, except that Budiansky’s perspective was also shifting, meaning that there were at least a trio of opinions at play concerning who Deathlok was and what he should be. While most of the story details are lost to time, I can remember that this final issue went through five drafts of the plot before we were simply out of time and had to go with what we had at that point. (My memory is that every draft after the third was an exercise in futility, where some bits were changing but nothing was getting better—and that everybody involved was growling more and more frustrated. Honestly, this may in part explain why Bob gave the ongoing series to me) On top of that, the first two issues had been drawn by Butch Guice over the course of about eighteen months. The project hadn’t been scheduled yet, and so it was constantly getting set aside for other things. In the end, once Butch took over penciling DOCTOR STRANGE, he had to give up finishing DEATHLOK. Fortunately, Denys Cowan was able to step into the breech and come on board to complete the series. His first issue, Book Three, had been inked by Rick Magyar, and the pair were a dynamite combination. But for some reason I can’t remember (possibly just the fact that it was all so labor-intensive—these issues were each 48 pages in length, and now that they’d been scheduled, the deadlines were tough) Rick couldn’t do the last issue. Denys suggested that we bring in Kyle Baker to ink this last issue, which we did. But when Kyle brought in his first pages, we were all a bit shocked at the results. Kyle had approached the work with a very loose, very linear style. Much of the beauty and sophistication of Denys’ work was getting lost in translation. Bob had a conversation with Kyle about what he was doing and Baker went away to try to fix the pages. What he brought back in was better, but still not what everybody was happy with. So we parted ways with Kyle (though we did use the pages he’d inked, with maybe some touch-ups from John Romita and his Romita’s Raiders crew) By this point, though, the book was running late, and we ended up having to bring in a bevy of inkers to split up and finish the job in time. So it’s really not the way you want to craft the finale of a project that’s been worked on for so many months. The cover was a problem, too. The first three issues had sported lovely painted covers by Joe Jusko, Bill Sienkiewicz and Jon J. Muth (Bob had all of the best painters at his fingertips as we were the ones putting out the Marvel Press Posters in those days, which were often painted, and paid well.) For this final issue, Denys wanted to paint the cover himself, and Bob agreed. But like with Kyle’s inking, when Denys brought in what he thought was the final piece, Bob and I weren’t satisfied with it. I’m not certain, but I believe this may have been Denys’ first time attempting a painted cover, so he wasn’t as adept with the medium as he would later become. He did take the piece back and rework it, resulting in the cover you see above. It’s not bad, but it does feel a bit unfinished and sketchy. (That Harlan Ryker head in particular.) All of the drawing is good, but the color technique isn’t fully realized. Anyway, despite all of these difficulties, the limited series performed well, and the ongoing title was scheduled to be launched the following year. To prime the pump for newsstand audiences (the ongoing title would be available on the Newsstand, but the limited series had been Direct Market only) these four issues were reprinted as Specials prior to the first new issue. And Denys did a new cover for it that was a bit stronger.

Monofocus

Not much to mention on the media side this week that’s new. The climax of EXTRAORDINARY ATTORNEY WOO was terrific and enjoyable, as was the news that, in a rare instance, the show would be mounting a second season which would be released in 2024. So something to look forward to. I’ve been continuing to barrel through THE SANDMAN, finishing up just as the extra bonus episode was dropped. So I’m not quite at the finish line there yet. Simultaneously, I’ve continued to pick away at NEVER HAVE I EVER’s third season, which is still charming. And I closed out KAKUGURUI TWIN. (Poor PAPER GIRLS has been languishing now for over a week, which decreases the likelihood that I’ll ever get back to it, what with other shows continuing to drop. And I found that I needed to source missing episodes of LIAR GAME which were missing from YouTube, so I’m still in the midst of that series. I’m certain that I’ll continue onward into its sequel LIAR GAME 2 once I finish it.

In the world of publishing, I enjoyed revisiting the Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips graphic novel PULP in its new PROCESS EDITION form. For all that I make comics for a living and have read dozens of Brubaker scripts over the years (I still have a folder of CAPTAIN AMERICA scripts somewhere) and seen Sean’s layouts before, it was nice to have the entire process contained in a single package. Honestly, it really is like a textbook showing just how these creators craft their award-winning stories. It’s great, and highly recommended, in particular to those who are working to follow in their footsteps as creators. (It contains the entirety of the graphic novel in its final form as well as the earlier process work, so it can be read and enjoyed apart from teh background material as simply a reading experience.)

I also put a big dent in THE LIFE AND CAREER OF DAVE COCKRUM from TwoMorrows Publishing this afternoon, a very fine volume on the life of the best super hero character designer of the 1970s. It’s packed with behind-the-scenes artwork and photographs and includes a detailed section on the creation of the All-New X-Men, as you’d expect that it would. But it also covers all of the other facets of Cockrum’s career, including his fan press days and his time designing models for Aurora and so forth. I bought it in the Hardcover version containing a few extras (and in typical fashion, I’ve wound up with two copies) but the more affordable Softcover is equally fine. I think Dave’s work is a bit underrecognized for the impact it had on the field, so it’s nice to see him and his work spotlighted in this manner. And author Glen Cadigan totally gets across that Dave was a huge fanboy.

That’s it for this time. I always underestimate how long one of these releases is going to take to write up, and am astonished to discover that the sun has set while I was pounding away at it. Oh well, live a little bit and I’ll report back in seven days!

Tom B

Thanks for the excellent Tom Palmer memories, but I'm never buying you dinner.

About Marty Nodell, I can say with some authority that the story you relate about GL’s origin is more certain than “legend has it.” Marty told me approximately the same story while I attended my friend’s wedding (Marty was my friend’s uncle). The only thing I would add to what you wrote is that Marty told me that it was specifically the 1940 hit movie “The Thief of Baghdad”’s use of a magic, wish-fulfilling lamp that gave him the idea to give GL’s lantern, which was indeed inspired by a subway worker’s lantern, a similar power.