Went down the rabbit hole a little bit this past week in looking back at some of the earliest expressions of the Marvel characters in other media. The oldest of these was the syndicated series THE MARVEL SUPER HEROES which debuted in September of 1966, and featured segments devoted to the Hulk, Captain America, Iron Man, the Sub-Mariner and Thor. Even at the time, this was the second-stringer squad, Marvel’s two best-selling properties, Fantastic Four and Spider-Man having been held back to eventually feature in shows of their own (though Spider-Man was initially intended to be a part of THE MARVEL SUPER HEROES and features in some of the earliest advertising for the show. Iron Man was substituted instead.)

These cartoons, which are unavailable today outside of bootleg copies and often crappy videos on YouTube were crude even in their time. They took the conceit of limited animation to a ridiculous level. On the other hand, the stories were mostly adapted directly from the comics being drawn from, and the artwork of Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Gene Colan, Don Heck and others was directly ported over for use in the series, with some mouth-movements added and limbs occasionally flailing. These were not great cartoons, but they were good at capturing a lot of the flavor of the Marvel style of that period.

This show was among my first exposures to the Marvel characters, and it went back into syndication in the late 1970s after the Hulk started headlining a successful live action show, this time under the title THE INCREDIBLE HULK AND FRIENDS. Consequently, the original opening title sequence for the show had been snipped off of most of the prints, and for years was thought lost. It has since resurfaced, and can be watched in full at this link.

Time now once again to answer some queries from you folks.

Leigh Hunt

Only thing I didn't like about Avengers Inc were the covers. They were distinctive but didn't really seem to match the title for me. Do you think something like this can dissuade buyers? Would a more standard superhero-type art have made a difference possibly?

Maybe, Leigh? Given that the series proved unsuccessful, it’s hard to conclude that anything abut it truly worked. That said, I was happy with the covers that Daniel Acuna did and the approach we took to them—including changing up the text treatment of the logo for each issue in the manner of PLANETARY. But if they didn’t work for you, I can’t really argue with that.

J. Kevin Carrier

I assume there's a story behind the crowbar in your office. An homage to Gordon Freeman (or even Dirk Garthwaite)? Or just an acknowledgement that being a comic book editor requires brute force as often as finesse?

You know, Kevin, David Tennant once asked me more or less this same question while on a visit to the Marvel office. And I’ll tell you what I told him: Respect! (a line I ripped off shamelessly from SCTV.)

Zach Rabiroff

what, these days, is the day-to-day purview and work description of a Marvel Editor in Chief? How do the EIC's responsibilities compare to those of group editors, the publisher, or the company higher-ups? Who, in the end, actually sets eyes on a comic book before it hits the stand, and in what order?

The Editor in Chief exercises broad authority over the entirety of the line, Zach. He’s the person who ultimately decides what projects get published, at least from an editorial point of view. And he can have as granular an impact on any given series as he may want to, though he never edits any series directly. So he reads a bunch of everything, but he’s not scrutinizing every issue or every book. He’s got other things to deal with, including interfacing with all of the other departments of Marvel and the larger divisions of Disney. The person credited as Editor on any given book is the person who exercises direct and immediate oversight and authority on it, backed up by at least one Assistant or Associate Editor typically. A Senior Editor will oversee the efforts of a number of Editors and Assistants, and an Executive Editor functions as the XO of the division, having oversight on typically about half of the line but also having broad impact on all of it. So an issue of AVENGERS, let’s say, is edited by me; my on-the-books job description is Executive Editor, but on that title, I am the Editor. I hire the creative team, with input from the EIC as well as the Talent Management department, which tracks all of our creators, making sure that our contractual obligations to them are fulfilled and charting when a given creator might be available for a new assignment. I read and comment on the script, as do Associate Editor Annalise Bissa and Assistant Editor Martin Biro to a lesser extent. The three of us track the series throughout its production and look over and okay each page of art at each stage of development. When it’s time to letter, we’ll wind up reading a given issue somewhere in the neighborhood of four times each, making alterations and catching typos and improving clarity wherever possible. During that same time, an independent proofreading team will read the book twice, and it will also be read by an otherwise-uninvolved Read-Out editor in order to get some fresh eyes on it. If this book wasn’t being edited by an Executive Editor like myself, it woudl typically also be read over by the Senior or Executive Editors above that editor in the chain of command, or often both. And after the entire book is completed, it passes through a final content review that flags any elements that might cause us trouble, either legally or in the manner that it might be misinterpreted by the readership. On an as-needed basis, the EIC may be called upon to review some aspect of the issue at this point to adjudicate whether something might need to be revised or not. And still, despite all of those eyes on it repeatedly, every book we put out manages to find some way to have embarrassing mistakes in them.

Kurt Busiek

Regarding AVENGERS 2 -- if my hazy memory is right, I suggested that we swap in the cover for issue 3 to replace the Scarlet Witch cover Bob didn't want to use, because there wasn't time for George to do a new cover, and we were kind of one step out of sync with the covers anyway -- the Queen's Vengeance debuted in issue 2 but we didn't show them on the cover so solicits wouldn't give it away. But I could be wrong about that.

I did suggest doing the Wonder Man cover for issue 3, and was very happy with it, because due to the circumstances, that cover wouldn't be used in solicitation, so we could actually have it be a surprise to readers. And George could get it done in time without slowing him up on the issue he was working on.

[I also wanted to do an arrow-shaped caption on the cover saying "One of the Avengers on This Cover Will DIE in This Issue! But Which One?" -- pointing directly to Wonder Man, since he faded back to "dead" by the end of the story. But you were sensible enough not to do it.]

I’d tend to trust your recollections of these events more concretely than my own, Kurt.

Jeff Ryan

DC infamously put out The Wit and Wisdom of Lobo, a 64-page blank book. Some people bought it unaware of the joke, hoping for 64 pages of action featuring The Main Man. Have there been any ideas pitched to Marvel that may have sold, but were shut down because it would feel too much like ripping off the audience?

I’m sure there may have been some over the years, but I can’t recall anything quite like that LOBO release, Jeff. The closest similar thing I can recall pitching was when I was working on SKRULL KILL KREW in the mid-1990s. For a few days there, i was hot on the idea that we’d release the first issue of the book with a separate modular cover for an issue of X-MEN—the idea being that you could put it in front of your issue and then nobody else would know that you were reading a Skrull book, like the book itself was in disguise. I can remember Bobbie Chase staring at me dumbfoundedly as I described this idea to her, and it never came up again.

Matthew Perpetua

From what you've written in previous newsletters, Pepe Larraz has been stockpiling art for Blood Hunt for some time, and Daniel Acuna has been far enough ahead on Avengers Twilight that you could double-ship the first two issues. How often do you get to have artists work far in advance of publication, and what's the average amount of time between a comic being drawn and getting shipped in this era? Is working in this way something that is only prioritized for particular star artists and high profile projects? Are there any down sides to working well in advance of release dates?

It depends entirely on the project and the circumstances, Matthew. Obviously, it would be ideal to have a ton of lead time on every project, and wherever possible, we like to try to give our creators as much lead time as is possible. On the other hand, sometimes there’s a pressing need to turn material around a lot more quickly. For example, for Free Comic Book Day in, I think it was 2019, I turned around the ten-page DARK AGES preview story with Tom Taylor and Iban Coello in two weeks, from the starting gun to the book leaving house. In that case, it was necessary because another project had shifted on the schedule, and so having it previewed in FCBD was no longer advantageous, and we needed something else that could fill the gap. And the downside of having to work so far ahead is obvious: often, details change by the time you get to when the project is going to come out. For example, on BLOOD HUNT, we needed to show Iron Man, but the new armor that he was going to be wearing at that point hadn’t been designed yet. So we wound up getting Pepe to design it first, so that we could use it in BLOOD HUNT and it would be ready when INVINCIBLE IRON MAN needed it. But for every time we’re able to catch such a thing and make adjustments, there’s some other instance where a fix isn’t so obvious and you end up with a bit of unintended discontinuity.

Evan “Cool Guy”

My question is specifically about Doctor Doom but also may speak to a larger trend of sorts. Dr. Doom is very popular and as such, has become something of an anti-hero as opposed to an outright villain. The last book I can really remember him being "evil" in is Matt Fraction's FF I think? When Scott Lang avenged his daughter's death.

Granted, in Cantwell's solo series IIRC (spoilers ahead) he blew up an entire alternate universe, but somehow that doesn't actually come across as badly and he's able to retain his noble anti-hero status. I guess my question is, would you guys allow a writer to pitch an in-continuity truly evil Doctor Doom, of the type who murders an innocent child like he did with Cassie Lang?

It seems to me like this process has happened with a fair share of villains, and I wonder if a lot of thought is put into it or if it's simply a natural consequence of their popularity? Not saying it's bad by the way, just interesting!

I would say that it has a bit more to do with our feelings toward what constitutes villain, Evan. Back in the day, the average super-villain might be using their powers to steal stuff, and that was good enough. But today, such characters often feel like jobbers. General mayhem and destruction is easier, but it can get repetitious as well. And as our material has gotten more sophisticated, it’s become more clear that the nature of evil is subtler and more pernicious often than can easily be punched in the face. That all said, I think that Doctor Doom has made enough appearances in a variety of places in recent years where his menace and villainy have been amply on display. But part of what makes Doom such an interesting character is his nuance. He has a certain flair, a certain sense of style, a way of going about his business that reflects his education and refinement. So he’s not likely to simply kill a bunch of people without what he considers a good reason. So I’d certainly might approve a story in which Doom was truly evil (no writer needs me to approve their ability to pitch, but not every idea that gets pitched gets implemented) but only in so far as it was reflective of what has been established about Doom’s outlook, personality and character.

Karl Kesel

A while ago you mentioned how Wolverine once struggled to fight a handful of Hellfire goons ("Wolverine Fights Alone!"— an issue of X-MEN that I waited on the EDGE OF MY SEAT for!) yet today that would be a walk in the park for him. That sort of "mission creep" or "power creep" in comics has always bothered me, the obsessive desire to keep upping the ante or "take it to the next level" (as Mike Carlin liked to say). It seems to me that leads to total Event Publishing (something Dan Jurgens predicted in the 80s)— where the fate of the world! The Universe! REALITY ITSELF! is always at stake. And it makes me wonder where all the wonderful, smaller, more self-contained "This Man, This Monster" stories fit in.

Related to this is that at the heart of many superheroes is the dichotomy of the Hero Who Struggles and the Hero Who is The Best. Spider-Man certainly started out as a Hero Who Struggles, but after 60 years he's a seasoned, experienced pro, and the only way to make him struggle is to have him constantly go up against stronger and more overwhelming foes/situations… which he overcomes… which only makes him even more experience and accomplished at what he does. It seems to be a vicious cycle that will sooner or later eat itself.

I believe this is where legacy characters come in— like Wally West becoming the Flash, or Miles Morales as a less-experienced Spider-Man. This is how we see *a* Spider-Man, at least, struggle against much smaller threats and odds.

But does that mean Spider-Man— I'm talking Peter Parker here, not the *idea* of Spider-Man— can Spider-Man never again be the Hero Who Struggles? The hero who spends most of an issue trying and trying and trying again to shoulder and lift a literally crushing weight that he's trapped under? (A Ditko reference, yes.) Can a character like that be "re-set"— WITHOUT a reality-altering Crisis or a partial/radical "de-powering"— or do we have to accept that these characters grow and change… and now it's Miles' turn.

Obviously "This Man, This Monster" happened right after the Galactus trilogy— setting the standard for how to bring your characters back to "ground level." But that was in a time before constant, company-wide Events which, to my mind, effectively wipe out or at least drown out the smaller moments— and even mid-sized moments like the introduction of Wakanda and the Black Panther. Nowadays those sort of things have to be PART of a big event, or it's like they never happened.

Some of this "power creep" is a natural extension of new people playing in the sandbox. Hell, Barbara Randall Kesel and I revamped HAWK & DOVE, purposefully making them much more than they were before. And that was fun! Exciting! And well-received! I'm not saying this shouldn't happen, not saying it's bad. Just that it feels like that's ALL that is happening these days.

I don’t know that it really is all that’s happening these days, Karl. I think it just may be where you happen to be looking. But to use an example close to home, I think that most of the situations faced by the characters in Ryan North’s current FANTASTIC FOUR run have more clearly been in the small camp than the large one. And absolutely, Peter Parker could still struggle to lift a big thing off of his back—the thing may now need to be proportionately more heavy, but as we establish the elements of the story, that’s entirely within our control. No, i think what we’re seeing more and more these days—and I’d something I’ve been advocating about pushing back against—is a lot of super hero stories becoming insular affairs. In other words, stories in which Super Heroes grapple with their super problems, confiding in their super friends and they go about their super affairs and grapple with their super rivals without any regular human being involved. Super heroes these days are way more likely to have romances with other super heroes, it seems, than with civilians—civilian supporting characters are relatively thin on the ground. And so all of this creates a greater distance between the heroes and the readership, apart from the hardest core readers who are entirely invested in the fantasy world. As Steve Wacker used to often point out, our heroes are only heroic if they’re saving innocent regular people. Apart from that, they’re simply narcissists dealing with their own baggage regardless of anybody else who might be caught in the crossfire. So i think it’s less about how strong Spider-Man is considered to be today, how accomplished as a hero, and more about what the storytellers choose to have him do with that strength.

JV

Tom - do you think War comics (not necessarily by Marvel) have a place in modern comics? Is it too sensitive a subject that can be trivialized? or is there room for it? Should it be 'realistic' (like the 'Nam') or is there room for a WW2 Invaders series?

I am torn a bit because I love the old Roy Thomas Invaders and All Star Squadron series, as well as Garth Ennis more recent (and brutal) explorations of past conflicts in his war stories. It is a tricky to write about modern conflict without stirring some justified emotions.

I feel as though there’s room for every possible genre in comics, JV, assuming the work is done well. But I do think the sorts of bloodless war-is-an-adventure series that dotted the comic book landscape in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s are relics of a bygone era, one in which we didn’t truly have an understanding of the cost of waging war on those involved. It’s much more difficult to field a Sgt. Rock or a Sgt. Fury today in any way that seems remotely realistic, because while there’s value in service, combat isn’t an adventure story. Now, you can certainly do stories about characters in those situations, powerful stories if you do them right. But I don’t think we’re in a place where they’re ever likely to become as ubiquitous as they once were. They lack a necessary verisimilitude for most contemporary readers.

Carlos

Good evening Mr Brevoort, if the question bothers you, ignore it, I am very curious about your stag in X-men but asking you about that would seem very daring to me, although if Mr Claremont's stage is your favorite I like that because for me it is too, (Kitty and Wolverine They are my favorites and they are because of Mr Claremont) and I know that Spider-Woman has a regular series but my question is if there is any possibility that in the near future Spider-Woman could be part of a team and we will see her in another series being part of a MARVEL team and sorry if I have bothered you, thank you very much Mr Brevoort.

You’re always welcome to ask a question, Carlos, provided that you’re not asking the same question incessantly week after week. In terms of Spider-Woman, I don’t know offhand whether we’ll be seeing her much outside of her series. I can tell you with some confidence that she won’t be in any of the new X-Books. But that’s about all I know.

Pierre Navarre

To quote that article : Who’s Your Stilt-Man (an obscure character you're particularly fond of) ?

Oh, there must be dozens of them, Pierre, especially in the manner that this piece defines such characters. To begin with, there’s this guy:

Behind the Curtain

What I’m reproducing for you this time is a series of notes taken at a lecture about storytelling delivered by John Romita Sr. to the Marvel junior editors on October 25, 2000. I had to rescue this text from an old document in an not very accessible format, which is why the copy has been poured in below rather than reproduced directly. But hopefully, this’ll make it all easier to read.

Editor School Notes

10-25-00

Penciling: John Romita, Sr.

John Romita Sr. claims that he is not an "artist with a concept," but rather someone who can "take a plot and turn it into something better."

John feels that editors need to watch artists closer by comparing art to the plot and making sure that the art holds up to the original intended work. It's all too easy for an artist to ignore or pass over important plot points, but some of those problems can be fixed easily.

Some problems for artists can be solved in the plotting stage. Keeping the plots clear and concise. By raising the complexity of comics, we inevitably lower the clarity of them.

Sometimes comic book writers confuse complexity and obscurity with sophistication.

The pictures should be able to tell the story without copy.

John feels it is very important to establish a scene change with some type of shot of the new location at the beginning of the scene. After the characters' locations have been established, it is not necessary to establish the scene every time they appear after that.

A major focus of John's was continuity. He focused on three major types of continuity:

Panel to panel continuity: Make sure that the reader is able to follow what is happening in the scene (or in the change of scene) without great confusion. Establish scene changes, character movement, etc, so that everything flows logically from panel to panel.

Continuity of events in the story: Making sure that the effects of one panel in a scene carry over to the following panels in that scene. If a window is broken and the room is scattered with glass, the glass should be there in following panels. If Dr. Strange picks up a cup of tea in one panel, he should be holding that tea in the next panel.

Continuity of character, style and design: Characters should look, act and feel consistent, so as to make them believable as possible. Peter Parker should act and look like Peter Parker and never be mistakeable for some other character.

Even in the most intricate of plots, there is still a lot for the artist to fill in. It is the editor's place to act as a preventative measure... so that the writer and artist cover all the necessary bases in creating the story.

A good way for the artist to gain a focus and to build for major events is to go through the plot and circle major events, seeing which panels are the page's focus panels and which pages are the most important in the story. With that knowledge, it is much easier to make the story work and build properly.

John feels that storytelling is a form of micromanagement. The artist should be the one to make the story flow smooth visually so that the writer doesn't have to worry about that (by providing strong, established transitions, page breaks, etc).

John said that one of the biggest shortcoming in comics today is that "no one stays with the team." People aren't absorbed in the characters' continuity and that causes inconsistency.

Genuine gestures and motions get a response from the reader. Characters should look at each other. Head and shoulder shots are boring...add the hands to liven it up. Characters should be drawn with their mouths open if they are speaking. They should not have their upper-eyelids showing if they are intense.

Don't be afraid to show characters from behind. It makes them more real. So often, the back of a character's costume or their hair has never even been established!

According to John, the reason that the Image style of storytelling doesn't work as well is that artists are more intent on creating dramatic poses and pin-up shots than focusing on storytelling aspects.

Artists should draw from life, not from comics. Don't use other comics as an example or the mistakes that came before get repeated.

Backgrounds cannot be done mindlessly. If they are done with the same kind of textures as the characters, the characters get lost in the background. Artists should use different textures to show the characters and create focal points.

Overcropping panels is like sitting in the first row of a movie theatre. It's hard to take it all in and feels claustrophobic. Pull back so as not to make the reader feel like they're missing something.

If the page's layout gets too elaborate, it takes away from the story. If a reader can follow the page without getting misled, then the layout is effective.

We don't want people looking at comics as "old stuff." But at the same time, the "new stuff" isn't always effective. Try to create new variations of a classic theme. It is hard for new artist to create variations if they don't know the theme, though!

Some young artists want to "make the industry better," but often they get sidetracked and they forget the original purpose of the medium: to entertain!

Find the "bomb," or the big event, in the story and build up to it. If every event is made into a major event, then the story will have nowhere left to build to... and the pay-off will lose its effectiveness. If the story's "bomb" is located before the artist begins drawing, he can build to it throughout the issue and have a much stronger pay-off.

Pimp My Wednesday

We’re winding down on AVENGERS material, with each issue bringing me one step closer to my last. So pickings will grow increasingly slim for a while.

AVENGERS #10 features the wrap-up to our “Twilight Dreaming” arc by Jed MacKay and C.F. Villa (not Francesco Mortarino as this mock-up indicates. it contains a one-on-one confrontation between Kang and his rival for the Missing Moment, Myrrdin, as well as a big fight with the Twilight Court and a confrontation between a pair of Avengers and Nightmare.

And FANTASTIC FOUR #17 welcomes new regular penciler Carlos Gomez to the series, where he’ll be working alongside writer Ryan North. This time, the excavation of the remains of a figure in a centuries-old Fantastic Four costume leads into a trip to the past and a surprise-filled confrontation with an old enemy.

And over in the digital world of AVENGERS UNITED, Thor and the Black Panther take preventative action against the alien Brutes that the people of Ghesh have recently sent against them. It’s written by Derek Landy and drawn by Marcio Fiorito.

A Comic Book On Sale 60 Years Ago Today, February 4, 1964

Hey, today is the 60th anniversary of the release of DAREDEVIL #1, the final headline character of the first wave of Marvel heroes! And it was a bit of a struggle to get to print. The impetus for doing the series at all was that publisher Martin Goodman had determined, rightly or wrongly, that the rights to the original golden age Daredevil had fallen into the public domain. As that character had been popular, Goodman suggested to editor Stan Lee that Marvel put out their own version. Lee turned to AMAZING SPIDER-MAN co-creator Steve Ditko about working on the book, since Goodman was very clear that what he was looking for was “another Spider-Man”—Ditko later said that Lee told him that they could essentially just do the original golden age version of the character or make something new up. But Ditko wasn’t into producing a knock-off of his most successful character and turned down the assignment. Lee then turned to Jack Kirby to work up a design for the new character while he made a longshot outreach to another creator he might be able to get to work on the series. Bill Everett had been a mainstay of the firm from its earliest days (where he created Namor the Sub-Mariner) up through the late 1950s when the company scaled back dramatically. Since then, he had left the field, and took a job at a greeting card company. Lee, though, talked him into doing DAREDEVIL. In conceptualizing Matt Murdock, Everett was inspired by his own daughter Wendy, who was herself legally blind. DAREDEVIL #1 was horrifically late—Everett’s day job kept him from being able to devote all that much time to it. (He also had a bit of a drinking problem that didn’t help matters.) The book missed its intended print date, an almost unpardonable situation in those days, where a company would pay for their press time whether they printed a book or not. Either AVENGERS #1 or X-MEN #1 (opinions vary) was swiftly thrown together to fill DAREDEVIL #1’s printing slot. Several months later, Everett still wasn’t finished, and Lee had no choice but to call the job back in house. Steve Ditko and Sol Brodsky did a massive jam session to complete pages, adding in missing background and finishing inking. Everett had also loused up his original splash page in some manner that wasn’t considered salvageable, so Kirby’s design shot of the character was adjusted (Everett had changed the costume somewhat) and pasted up into a new, sparse splash. That same figure was used on the front cover, though here Everett added the background figures and the oddly arranged vignettes of Matt, Foggy and Karen. A particular strange note: that headshot among the Fantastic Four of Sue isn’t a Sue had at all. It’s a Millie the Model head that was slightly altered for this use. In any event, DAREDEVIL had a rocky start for its first year or two. Joe Orlando wound up illustrating issues #2-4, but he and Lee weren’t sympatico, and he often wound up having to draw 30 pages for a 20 page story, with a chunk of his work unused (and unpaid for.) After that, Wally Wood came on board, and over the next few issues revamped the book from top to bottom. It was Wood who designed Daredevil’s familiar all-red costume (though he’d intended it to be black and red.) But Wood wasn’t happy with the Marvel approach to comic book making in which the artist did the majority of the plotting, and so he quit after not too long of a time. It was really John Romita taking over the series thereafter that stabilized the book and began to improve its flagging sales. Romita was succeeded by Gene Colan when he was called upon to take over AMAZING SPIDER-MAN following Ditko’s departure, and Colan stayed with the feature for about a decade, on and off. For its first two decades or so, DAREDEVIL was something of an also-ran title, perpetually hovering just above the cancellation mark. It wasn’t until Frank Miller came on board and gave the character a more noir Batman-style sensibility that Daredevil really attained a sustained measure of popularity.

A Comic I Worked On That Came Out On This Date

SECRET WARRIORS #1 was released on February 4, 2009 and was an outgrowth of the SECRET INVASION crossover. During that crossover, Nick Fury had reappeared, coming in from the cold and recruiting a team of “caterpillars”, young people who had been flagged as possessing super-abilities but who had not yet entered the world of heroes an villains. Fury needed such a team to go up against the alien shape-changing Skrulls, who had been infiltrating the ranks of Marvel’s assorted heroes for months. The idea was to give Fury and his crew a new series once the Event was over. But it became clear that, with everything else already on his plate (including a SPIDER-WOMAN series he wanted to do with frequent collaborator Alex Maleev), Brian Bendis wasn’t going to be able to write SECRET WARRIORS long-term. So he suggested that we recruit a newcomer whose work had caught his eye, Jonathan Hickman, to first co-write the series with him and then to completely take it over. Brian didn’t really know Hickman, but he’d been impressed by the newcomer’s work on his creator-owned projects such as THE NIGHTLY NEWS. Jonathan, who had just started doing little stories in MARVEL COMICS PRESENTS at Marvel and was just finding his footing, was all in on this idea. The artwork would be handled by Stefano Caselli, who had showed up just in time to do the CIVIL WAR: YOUNG AVENGERS AND RUNAWAYS limited series and who I was trying to find a home for. And the initial story hook would be an idea that Brian had been looking for a place to implement for a while by that time; the revelation that, since its inception, SHIELD had been a creation of their enemy organization, Hydra, and Fury had unknowingly been carrying out Hydra’s master plan. True to form, Jonathan leapt into SECRET WARRIORS with both feet, and produced an outline for the first 66 issues. No kidding, it was 66 issues. The actual series only lasted for 27 and so the planning was scaled back along the way. But you can’t say he wasn’t ambitious. In fact, he was so ambitious, and had such a clear vision for the series, that virtually from the jump he was doing almost all of the writing on the title (as well as designing its striking cover set-up and logo.) I can recall, as we were putting issue #3 to bed, Brian asking me if we could take his name off of the rest of the issues, as he felt like he wasn’t doing enough work on the series to warrant it. I told him absolutely not, that I was going to credit him through the first arc at least, as his credit helped us to sell the book in, and his involvement in setting up the premise of the story and the series warranted it. But he didn’t want to take any credit away from Jonathan. While it was never a top-selling series, SECRET WARRIORS performed solidly for most of its run, and I regretted having to give up editorship of the book after issue #15. But I had junior editors to feed, and something had to give. But the relationship we’d established during SECRET WARRIORS led to me offering Jonathan FANTASTIC FOUR, and then led indirectly to his runs on AVENGERS and NEW AVENGERS, and finally to SECRET WARS. And a number of the caterpillar characters wound up appearing on the AGENTS OF S.H.I.E.L.D. television series.

Another Comic I Worked On That Came Out On This Date

AVENGERS #41 came out on February 4, 2014, and was deep into Jonathan Hickman’s run leading up towards SECRET WARS. We were already bannering the countdown to that impending Event here, a promotion that I thought was very effective. In any event, the only real reason I chose to spotlight this particular issue here is its cover. Because we knew this issue was going to be touching on the approach of the Earth of Universe 1610, AKA the Ultimate Universe, I chose to use this piece, which had previously run as the cover of THE ULTIMATES #1 several years earlier. This wasn’t a new recreation by artist Bryan Hitch or anything, it was the exact same piece of art that ran on that issue—one of the cheapest and easiest covers I’ve ever put out. We did pay Bryan for the reuse, in case you were worried. And the piece made its point in a way a new piece wouldn’t have.

The Deathlok Chronicles

It’s necessary to pause slightly in our survey of the history of the DEATHLOK series, and how I drove an otherwise solid title into the ground, to contextualize a certain aspect that made a lot of what follows happen. I’ve spoken previously about the two writers, Gregory Wright and Dwayne McDuffie. I had interned for both men while they were both on staff at Marvel, and so I had a very comfortable and congenial relationship with the both of them. The same wasn’t really true of the series artist, Denys Cowan. None of this was Denys’ fault in the slightest, he was never anything other than professional and respectful. But he was also way worldlier than I was at that point, an industry veteran of a decade, a seasoned pro. He was urbane and stylish and effortlessly comfortable in his own skin. And as seen above, he had even appeared in a nationwide add for Dewar’s scotch. The guy you see there? That’s the person who would turn up at my office to drop off pages and to get caught up with what was going on with the series.

Denys Cowan intimidated the shit out of me.

I was only 23 years old at this point, living on my own for the first time, and a lot less self-confident in who i was and what I was doing. This is not a great place for an editor to be, as it’s inevitably your role to be the ostensible grown-up, to carry out the needs and objectives of the organization and to adjudicate difficulties between creators and keep everything on time and moving in the right direction. But because his vibe was so strong, I never developed an effective rapport with Denys, we were never operating on the same level. I can’t speak for him, as I said, he was always a genuine professional. But being unable to relate to him effectively, I wound up making a bunch of different decisions that didn’t take his feelings into account. And when there were problems, I wasn’t able to convey them effectively or back them up as they may have needed to be. This is all on me, it was my inexperience that created these situations, and I owe Denys an apology for some of what went down in that time—all of which you’ll get to hear about in the coming weeks. As is the nature of any autobiographer, I’m perhaps likely to skew things slightly in my favor as I recount the rest of the run. So while Denys is on the book, assume that I acted 15% more poorly than I’m reporting, and that ought to get us into the correct zone.

To carry the overall narrative ahead some more in this installment, when the decision was made to go ahead with an ongoing DEATHLOK series, it was decided that we needed to reprint the limited series again for the Newsstand market. The bookshelf series had been sold in the Direct Market only, and it was felt that prospective readers of the new book, which would be available on the Newsstand, would need the background. So we released these four issues on a biweekly basis as DEATHLOK SPECIALS, with new covers by Jackson Guice and Denys Cowan on their respective issues.

Super Heroes On Screen

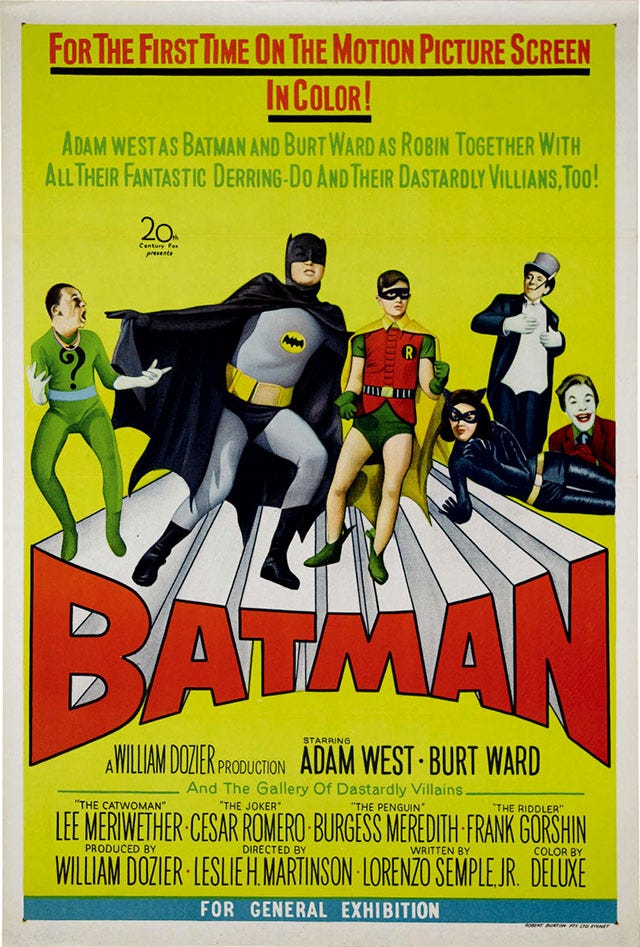

Nothing was bigger in 1966 than the BATMAN television show which aired Wednesdays and Thursdays on ABC. It’s a show that was largely reviled by comic book fans for decades for having turned the Caped Crusader and his milieu (and all comic books by extension) into a joke, a parody of themselves, a thing of laughter and ridicule. and there’s a lot of truth to that perspective—certainly, virtually every newspaper article or feature after it that focused on some aspect of what was happening in comic books was headlined POW! ZAP! That all said, while it turned the dial all the way up to 11, the stories in that first season of the show, several of which were adapted directly from the comics themselves, weren’t all that tonally different from what had been appearing in the DC comics of the time. The show burned bright, though, and wore out its welcome in just three years—partly because it was an expensive series to produce, and because the stylistic joke of the show didn’t prove flexible enough. Past a certain point, if you had seen one BATMAN story, you had seen them all. But all that said, BATMAN is a terrific series, one that pitches on one level for kids, who take all of its stylized crime and adventure seriously, and an entirely different level for adults, who are in on the joke and appreciate the innuendos and witticisms scattered throughout. And it looks great for a show that was produced in the 1960s. Part of that was because the producers were smart enough to leverage their popularity right at its height and produce a BATMAN film, one whose budget would pay for the creation of a number of regular props, such as the Batcopter and the Batboat. As a television series, BATMAN was ubiquitous during the 1970s when it ran in syndication. I watched it with great regularity, even before I was old enough to be buying and reading comic books. But once a year in New York, the ABC 4:30 Movie would run this other strange BATMAN film. It looked like the show, and starred most of the same performers, but it was more expansive, the score was different (it didn’t use that earworm of an opening theme song), and the pacing was different. It was odd, and must viewing whenever it would come around in circulation every year. The BATMAN show was the creatin of producer William Dozier, working closely with writer Lorenzo Semple Jr. At the time he went for his first meetings with ABC about running the series, Dozier had no awareness of the character at all, and stopped on his way to buy a couple of Batman comics from a local newsstand. He later claimed that he was embarrassed to be seen reading them on the airplane, and he couldn’t make heads or tails out of how to adapt them to a successful television format. It was in conversation with Semple that the choice was made: despite how ridiculous much of the material was on the face of things, they would play everything totally straight—to the point where the absurdity of that straightness would become funny. Nobody embodied this approach better than lead actor Adam West, whose steadfast yet subtle delivery hit this note expertly. He is great in this, and supported by winning performances by the regular supporting cast and most of the special guest villains, in particular the recurring ones. The film uses four of them, the four most popular, the ones that came from the comic books: Cesar Romero’s underrated Joker, Burgess Meredith’s perfect Penguin, Frank Gorshin’s transformative Riddler, and Lee Meriwether filling in for Julie Newmar as Catwoman. The film is a thick sauce—it’s often even more over-the-top than the show at that point, and its longer run time makes it just a little bit uneven. (The show had initially been filmed in an hour format, but was wisely broken into two half-hours in production, with the mid-show trap becoming a legitimate cliffhanger.) And maybe this isn’t the Batman that people want today, but I’ll always have a soft spot for its color and action and wit. It is a unique entity unto itself and succeeds at what it is trying to do.

Posted at TomBrevoort.com

Yesterday, I wrote about Jack Kirby’s earlier use of Thor in a fantasy story in DC’s TALES OF THE UNEXPECTED #16.

And five years ago, I analyzed the construction of the back half of FANTASTIC FOUR #1 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

We’re in the home stretch now, folks! So take care and we’ll do this again a week from now, okay?

Hat’s all, folks!

Tom B

As always, Tom, thanks for these. Your unflinching honesty in recalling your experiences with Deathlok are especially appreciated -- and, I think, helpful to anyone who's ever been young, stupid, and inexperienced in a creative job.

Speaking of old editorial experiences. Here's one I maybe ought to have asked you in an interview, but the topic never came up, so here it is. There has been an oft-repeated story (from John Byrne, Glen Greenberg, and others) that during the mid-90's, Steve Ditko had been in talks to make his dramatic, long-awaited return to Spider-Man for a project of some sort, only to drop the discussions after seeing Untold Tales of Spider-Man already in progress.

The story is eyebrow-raising on its face, if only because of Ditko's frequent and consistent refusals to work on his co-creation post-1966, even during periods when he had an active working relationship with Marvel. And even from the distance of time, I'm not sure how much you yourself are free to comment on it. But if I can ask your own recollections of the events, can you describe what happened here, and what you were actually aware of at the time?

Put me down as someone who loved the Avengers Inc character covers. I was in already for the creative team (Al Ewing is a must buy writer, and Leonard Kirk is underrated. Love his work everywhere I’ve seen it) but I’d have picked up those comics to flip through and consider buying on cover alone.

(That might not be enough.,. But I’m not a previews reader, so I’m not going to put a book on a pull list on a cover).

Anyway, I’ll remain sad it’s over. Issue 5 felt a bit rushed but the other 4 were perfect.